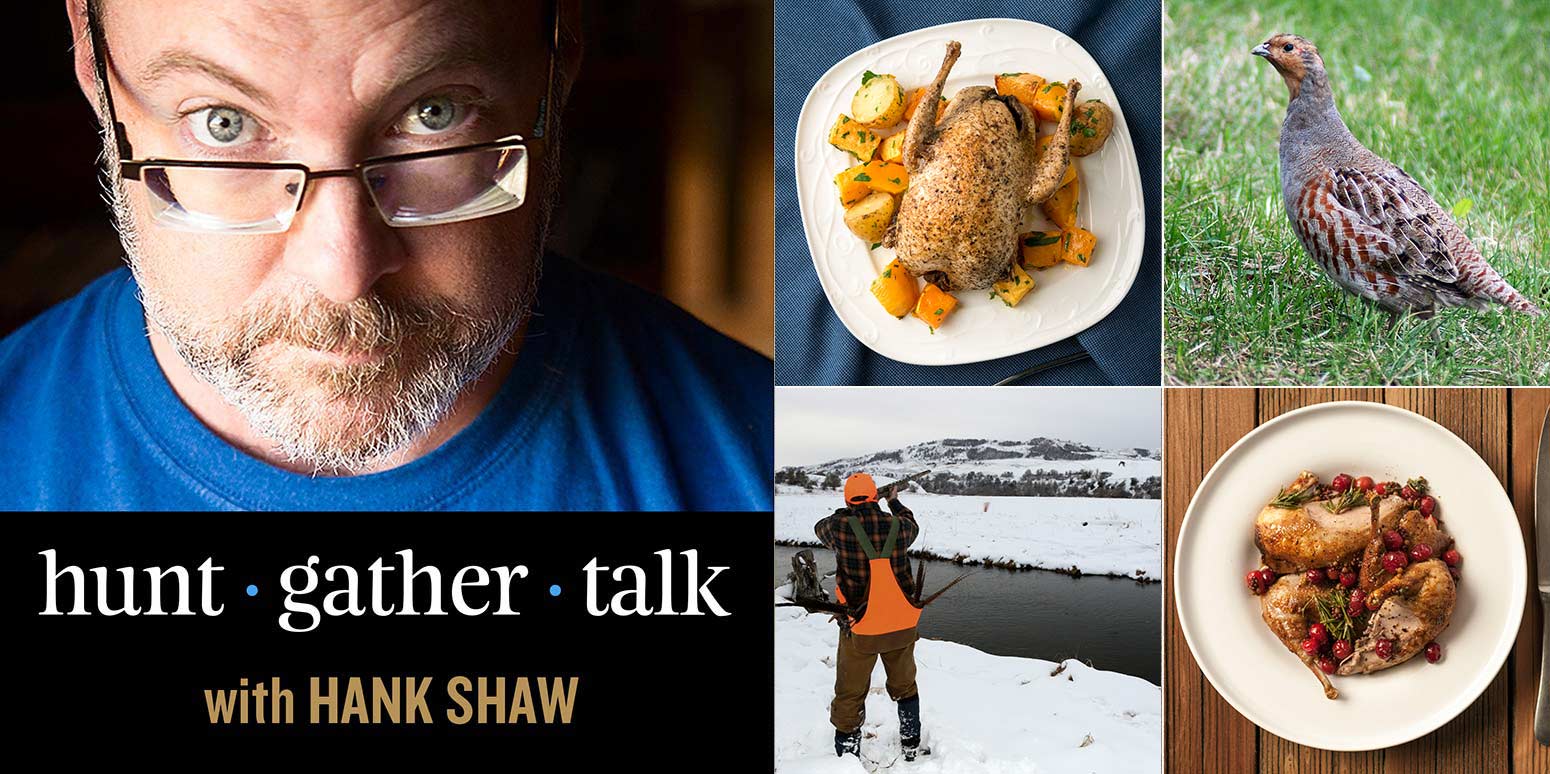

Hunt Gather Talk Podcast: Hungarian Partridge

December 23, 2019 | Updated April 30, 2021

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Welcome back the Hunt Gather Talk podcast, Season Two, sponsored by Hunt to Eat and Filson. This season will focus entirely on upland game — not only upland birds but also small game. Think of this as the podcast behind my latest cookbook, Pheasant, Quail, Cottontail, which covers all things upland.

Every episode will dig deep into the life, habits, hunting, lore, myth and of course prepping and cooking of a particular animal. Expect episodes on pheasants, rabbits, every species of quail, every species of grouse, wild turkeys, rails, woodcock, pigeons and doves, chukars and huns. And huns, the Hungarian partridge, are the focus today.

In this episode, I talk with North Dakotan Tyler Webster of the Birds, Booze and Buds podcast, all about the Hungarian partridge.

I’ve never hunted with Tyler, although we mean to change that next season, and I am not an experienced hunter of huns. But Tyler is, and it was fun to soak in the knowledge he’s gained over a lifetime of chasing these birds.

For more information on these topics, here are some helpful links:

- My adventures in Montana with Hungarian partridge, as well as a recipe using flavors of the prairies where they live.

- The ultimate method to cook a whole, small bird, like a hun.

- An overview on the biology of these birds, including what they sound like.

- A quick guide to hunting the Hungarian partridge, from Project Upland.

- Some of my favorite partridge recipes, including pan-roasted partridge with winter salad, partridge escabeche, which is like cooked, pickled Hungarian partridge, and of course simple roast partridge.

- I have several more recipes for snipe in my book Pheasant, Quail, Cottontail. You can buy a signed copy of that book here.

A Request

I am bringing back Hunt Gather Talk with the hopes that your generosity can help keep it going season after season. Think of this like public radio, only with hunting and fishing and wild food and stuff. No, this won’t be a “pay-to-play” podcast, so you don’t necessarily have to chip in. But I am asking you to consider it. Every little bit helps to pay for editing, servers, and, frankly to keep the lights on here. Thanks in advance for whatever you can contribute!

Subscribe

You can find an archive of all my episodes here, and you can subscribe to the podcast here via RSS.

Subscribe via iTunes and Stitcher here.

Transcript

As a service to those with hearing issues, or for anyone who would rather read our conversation than hear it, here is the transcript of the show. Enjoy!

Hank Shaw:

Welcome to the Hunt Gather Talk Podcast sponsored by Filson and Hunt to Eat. I’m your host, Hank Shaw. And today, we are going to talk about the wily gray partridge, which many of you know as the Hungarian partridge. It’s an introduced game bird brought here by European settlers as far back as the 1700s. But its real history here in the United States is only about 120 years old. It is thought of as the Quail of the North. They are fast flying and a challenging bird to hit in the field and they make for a great hunt, and even better eating at the table.

My guest this week is going to be Tyler Webster. He is an expert Hungarian partridge hunter from North Dakota and he runs the Birds, Buds, and Booze Podcast. Let’s get right to it. Welcome, Tyler. I am very glad to have you on the Hunt Gather Talk Podcast. It has been a long time coming. You and I have spoken before and we have not yet hunted the wily Hungarian partridge, but that is going to be the topic for the day.

Tyler Webster:

Well, it’s a good one. It’s one of my favorite birds to hunt. Even though we haven’t got to do it yet, I know it’s on the agenda for both of us for next year, hopefully.

Hank Shaw:

This podcast, the whole season, the purpose of it is to really super geek out on whatever the given animal of the day is. In this case, it’s the Hun. I’ve asked around and looking for … I’ve asked around looking for people who are the most insane Hungarian partridge hunters. There are a couple guys in Canada but your name popped up over and over again as one of the most hunt hotness guys out there. I figured it would be a really good opportunity to really geek out about the Partridge. This particular weird non-native Partridge that has been part of American game bird hunting history for several hundred years now. You are aware. So tell us where you are and what your background is and how you got started hunting the Hungarian partridge.

Tyler Webster:

Sure, yeah. So first of all, thank you very much for having me on. I appreciate you also coming on my podcast here a couple weeks ago, it was very kind of you. I am talking to you from northwestern part of North Dakota. I’m 35 years old, I’ve lived here my entire life. I started hunting when I was eight years old, sort of carrying a gun when I was eight years old with my grandfather. Back then, that would have been about ’91 or so. We were at an all-time record high for Hungarian partridge in the area that I live in. When I mean all time record high, you could drive down the road in any corner of a wheat field that you drove past, there would be a covey of Huns. Every single one.

You’d go out and it was not uncommon to see or move 15 to 20 coveys of Huns day, if a person was actually out there trying to actively hunt them. And then we kind of went through a little bit of a downspout in the ’90s when I was kind of getting my feet underneath me and kind of figuring out what I wanted to be when I grew up. Then all of a sudden, I got involved with pointing dogs in the mid-2000s and I found out that the Hun behaves pretty well for pointing dogs but they’re a real challenge. It takes a dog with a lot of manners.

Then as the Hun population came back, I started getting more and more away from pheasant hunting and other things and started getting more and more into Hun hunting. And in the last four or five years, that’s been pretty much my targeted species of choice. They’re an incredible little bird. They’re startling when they get up. They will absolutely scare the crap out of you. They will punish you. They will make you look like a genius one day, they will make you look like you’ve never held a shotgun in your life the next. They’re just a fantastic, fantastic game bird.

Hank Shaw:

The way I have described Hungarian Partridge, which is Perdix perdix for the Latin inclined out there, is that it’s the quail of the North. About 14 ounces is an average size bird and the feather. Males are a little bit bigger than the females but not a whole lot. And they covey exactly like bobwhites. It’s like a big blast and they explode and you … Either you get on them or you don’t. The cool thing about the times that I have hunted them, and I’ve only hunted them in Montana, is that they will fly and then because it’s Big Sky Country, you can see pretty much where they’re going to land so you can walk after them.

Tyler Webster:

You can, but they will also … They have this habit. One of the reasons that I love them as much as I do is because it seems like they’re always flushing just a little out of range, just a little out of range, just a little out of range and just like you said, I mean, up here, you can see forever. And they have several tricks that they’ll try to play on a guy. They’ll try to get some terrain between you and themselves, but generally you can kind of get a pretty good idea of where they’re going to go. I’ve, myself, followed a covey through nine flushes.

Hank Shaw:

Nine?

Tyler Webster:

Nine and not got a shot at them. Nine flushes, for those of you who haven’t hunted up here, that’s about five miles. Generally, they’re not going to just keep on going in a straight line away from you. They have a home territory that they’re comfortable with.

Hank Shaw:

I’ve heard it’s about 200 acres. It’s kind of like [inaudible 00:06:08].

Tyler Webster:

I think it varies based on population density. They’ll be in their same areas year after year, but they have … Eventually, you’ll start seeing a pattern. So you can push them to a point, I’ve done it a number of times in my life where they just don’t want to go anymore in one direction and all of a sudden, you’ll be walking up and the bird slosh away ahead of you and then they make a big swing around you and head right back to where they started from which is it’s almost like they have a home base. It can be super frustrating but they’re just an incredible game bird.

And when you say the quail of the North, I want those of you who do hunt quail, whether it would be Mearns quail or actually a fairly decent comparative as well, because of the way that they flush and how tight they hold. And when they get up, just like bobwhites. They’re almost twice the size of a bobwhite, really close to it, it seems like anyways, so when there’s 18 of them and they all go up at once, think of 18 bobwhites times two, that all go up at once. I’ve seen them make complete idiots out of some of the best wing shots in the world just because they just can’t focus and they’re so rattled by the sound. They’re just a really, really cool bird.

Hank Shaw:

Hey, I’d like to take a minute to thank the CC Filson Company for sponsoring this podcast. Filson is the original Alaska outfitter. They started in 1897 outfitting miners for the Gold Rush and the Klondike. And ever since then, they have been committed to making the best equipment available. I know, I’ve worn Filson for 20 some odd years both in the field and just around town. I am committed to their upland game gear. I think it’s the best, it stands up to everything and it lasts forever.

Be sure to check out Filson’s holiday gift guide at filson.com for all your hunter and/or gatherer gift needs. They have awesome stuff, not only for upland but for walking around town gear, travel stuff, as well as really good stuff for deer and duck hunting. So check them out at filson.com. Perdix perdix is native to Eurasia. We call it the Hungarian partridge. The initial plants were from Hungary in there but the Gray partridge is its other name.

Tyler Webster:

Right. The European gray partridge, yep.

Hank Shaw:

So it’s not a chukar. Basically, it’s the chukar’s pleasant cousin is the way it’s said.

Tyler Webster:

Well, at least the ones in my neighborhood are a lot more accessible for the average person, we’ll say. In fact, I’m going to be recording a podcast myself with a fellow that chases chukars. He’s 75 years old, he’s still getting up mountains, chasing those birds. But for most people that think of chukars, they’re going to think of the ones you shoot at a shooting preserve or a pen raised bird. Those are not what we’re talking about. But with Huns, they’re a little bit more closely associated with agriculture or at least they are around here. It tends to be not as unforgiving of country as the chuckar would generally like to live in.

Hank Shaw:

For sure. I mean, that’s one of the beauties of hunting the Hungarian partridge, is that you’re in this wide open, rolling, grassy area, you’ve got draws, you’ve got wheat fields, they seem to hang out in any kind of combination of small grain fields, pastures and fallow areas. It’s just a pleasant hunt. I mean, yeah, you could walk five, six, seven miles but that’s kind of a-

Tyler Webster:

Or a 12 or a 13.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, but it’s still, that’s the point. It’s not 13 miles at 10,000 feet chasing ptarmigan.

Tyler Webster:

Nope. It feels very civilized. I do it with the dogs and I’m sure we’ll get into that in a little bit. You can walk with another person and you just kind of walk around on these big expanses, whether it’s … In fact, one of my best spots that I found this year is literally half a section. So 320 acres or so, a half mile by a mile wheat field. Just a barren wheat field that was cut. There was six coveys of birds in that particular field but you just literally walk across it with a friend sitting there talking just like you and I are doing and then all of a sudden you look up and a dog standing and point and that’s when everybody starts getting a little bit twitchy.

He walked up there, you got your … Everybody’s walking up there, a little bit like Elmer Fudd, and all of a sudden, this group of birds that doesn’t seem like there’s any cover there for them to hide in explode out of nowhere. Then there’s usually four to six shots ensue and most the time no birds fall. It’s a very relaxing hunt. The country that they live in is so beautiful. They like old farmsteads. When you talk about draws and wheat fields and stuff like that, you can find them in old farmstead’s edges and sluice and such. So you don’t actually have to be … You’re not going to be pushing through super thick cover like you will for pheasants. You’re not going to be gaining and losing 5,000 feet of elevation like you will for chuckar, and you’re not going to be running into rattlesnakes like you will for quail.

Hank Shaw:

The one trick though is finding places that actually have Huns over the last four or five years now. I haven’t gone to your state, but I have gone to several places where I thought there would be Hungarian partridge hunting and there just wasn’t. They’re like, “Well, we’re not here anymore.” I looked up, and apparently they, much like rabbits, are extremely cyclical. Like you were saying, when you just started our conversation a few minutes ago that when you were a kid, they just were on every corner and then sometimes they’re not. I’m not entirely sure what causes the cycles. I know that they do not like wet springs. They’re an arid bird and they typically do very poorly if you have a bunch of rain in say March, April, May.

Tyler Webster:

Up here where I’m at, they are the last birds to nest and the last birds to hatch. Our Hun population is pretty much directly tied to if we have inclement weather in late June, early July.

Hank Shaw:

That late?

Tyler Webster:

Yeah. Our peak pheasant hatch in North Dakota according to The Game and Fish is June 15th. Generally, if the pheasant hatches June 15th, sharp-tails are a week after that and Huns are a week after that. So it’ll be right at the end of June or the first part of July. Generally, at that time of the year or at least the pattern has been over the last 15 years or whatever, we get most of our rain in May and early June. So the later in June you get you’ll start getting those warmer days. But it’s not even really so much the rain as it is if you get a really cold wet weather for a prolonged a period of time because the mom and pop partridge, they can have anywhere from 12 to 22 eggs or something like that.

So they have these giant clutches but they’re like the size of a ping pong ball when they’re born and they don’t get their flight feathers for 14 days. So they have to have warm weather. They also get hypothermic and die. The problem with that is, is that Huns won’t re-nest, at least, this is what I’ve been told from biologists who should know, but there’s no money going into Hungarian partridge research in this country, none at all. What they say may be right, it may be wrong, who knows, but they will not re-nest if a single chick survives.

Say, probably 14 eggs would be an average clutch, if one survives and the other 13 die, then there’s going to be a covey of three birds. So that’s the difference between a good year and a bad year, is if they have a pleasant warm, dry temperatures end of June, early July and it’s really only about the first two weeks of July that it’s really super important, then you’ll have the big coveys, kind of like we had this year. So now this year, I keep pretty … I’m very protective of my coveys. I know exactly where they are …

Hank Shaw:

It’s funny, [inaudible 00:15:05] mountain quail here in California.

Tyler Webster:

Right. And I’ve been hunting the same coveys for … There’s one covey that I’ve been hunting for 15 years. I just know it’s there, it sits there every year. It’s in this one particular area within, pretty much like you said, within a couple hundred yards, you’re going to find them generally. They could be a little bit farther one year, but this year, my average covey was about 14 birds. We’ve seen some coveys that were as big as 20 and we’ve seen a few of those sevens and eights. So our general rule of thumb with anybody that I hunt with is I asked them one favor, and that’s, “If you see a small covey …” When you’re walking up to a dog on point, you don’t know how many birds are there.

If it’s a small covey, say, seven to 10 birds, shoot the covey rise and then leave them be. Don’t go chasing them, don’t go and watch where they go and try to get up there and get on them again. Just shoot them on the covey rise, leave them alone. If it’s a big covey where it’s 18, 20 birds, if we knock, say, there’s me and one other guy and we knock three birds down out of the covey rise, we’re going to be watching that covey to see where it goes and we’re going to keep on chasing it and try to get a couple more out of it. But then we only hunt two coveys one time per year. After that, I won’t take anybody back into those fields. We’ll just leave them be.

Hank Shaw:

I just recorded a podcast with a quail scientist. And this guy named Dwayne Elmore of Oklahoma State University, he …

Tyler Webster:

[crosstalk 00:16:36] a couple months.

Hank Shaw:

There you go. He notes that at least quail … Now, partridges can be different. Quail coveys are very dynamic in the sense that the covey is not the covey is not the covey. So, the covey composition is fluid in the sense that if you shot out that seven birds, the four that are remaining will join another covey. And any given covey in any given spot can … It’s not always the same 14 birds in other words. I don’t know if that occurs with a partridge. It would be something that would be good to know because then whether or not your style of hunting Huns is actually beneficial or does it not matter.

Tyler Webster:

Sure. It probably doesn’t. The reason that I do it, and I think that it probably has a little bit to do with the time of the year as well. Our season here in North Dakota opens up … It’s always the second Saturday in September, so it’s the eighth, the 12th, the 14th, whatever it is. When that opening day comes, they’re absolutely still in their true family units. You’ll see a very discernible difference between the adults flushing and the little ones flushing. And sometimes if it was cold in early July and they had a failed nesting … I mean, I’ve seen young birds that can hardly fly September 14th that you don’t shoot. I just leave them because I don’t have any desire to shoot little itty bitty ones that can’t fly because there’s no meat on them anyways.

Hank Shaw:

[inaudible 00:18:09] veal.

Tyler Webster:

Exactly. But later in the year as it gets colder up here, for those of you who haven’t been to North Dakota, yes, the rumors are true, it does get pretty damn cold here.

Hank Shaw:

Really?

Tyler Webster:

I know. Today was actually beautiful. It was 45 degrees today, that’s probably pretty normal, but it’s going to get cold. You can bet on that. But as it gets colder and some of those birds do get … Whether it’s killed by hawks or owls or hunters or hit on a road or whatever it may be, they will start moving into bigger and bigger and bigger groups. So if there’s several coveys in the area and there’s a bunch of little five, six, seven, eight bird coveys, all of a sudden they’ll move all together and there’s going to be one big covey of 30 birds. That does start happening later in the year with Huns. And we started calling them super coveys. We’ve seen coveys as big as 40 birds before.

When you do move a covey like that, it’s very, very interesting because if you move them more than once, they’ll actually split back up into their original family groups and go different directions. It’s really bizarre. All of a sudden, first time they’ll go up, it’ll be 30, 40 birds and then 20 will go here and 20 will go here. Then when you hit one of those other groups, all of a sudden they split up into little groups of five, six, seven, and eight and they kind of go back to their old … It’s almost like they have a recall point, almost like quail do. And that seems to happen late October, early November, depending on the weather. They’ll start moving up, grouping up into those bigger groups.

Yeah, I would assume that they probably have to. I know that assumptions are bad, but I’m not a biologist, so what the hell do I care? The covey dynamics would have to be fluid just for genetic diversity, I would assume. I’ve often wondered, in a covey, what, say, this time of the year in mid-November, what the diversity of genetics would be if they would all, if there would be cousins and second cousins, or if it would still be mostly brothers and sisters. I mean, who knows exactly what that would be, but it would be interesting to know.

Hank Shaw:

Well, the churn is interesting. A study I read, it says the churn rate is 78% per year. That means 78% of them, don’t make it much past a year. And a typical Hun is two years old, typical that’s maximum lifespan. Then they haven’t recorded a Hun older than four, so they don’t live very long.

Tyler Webster:

Yeah. That would be pretty consistent with most game birds. I remember one of my favorite statistics I’ve ever read is that the average lifespan of a rooster pheasant is seven months. It’s like, well, if you’re going to be reincarnated as something, that would not be high on my list to be of being reincarnated as.

Hank Shaw:

You want to be waterfowl. The average age of a [inaudible 00:21:16] is seven.

Tyler Webster:

Right. Also, with Huns, they’re pretty aware that they’re at the bottom of the food chain. I mean, everything wants to eat them just like quail and everything else. So they’re being hunted literally morning to dark, and from sunrise to sunset and well past, all 24 hours a day for their whole lives. I’m sure that coyotes will take some but I don’t think they’re a major threat. It’s mostly avian predators, owls, hawks, falcons. Everything wants to eat them because they’re delicious.

Hank Shaw:

Hey, I’d like to take a moment to say that Hunt To Eat is a proud sponsor of this podcast, which makes sense because I own and wear a lot of their shirts, hats, and other gear. When you reach into your drawer to grab a shirt to wear to a barbecue or a conservation event, you always grab the same one, right? Well, you’re about to find your new favorite tee, head over to hunttoeat.com and check out their line of hunting and fishing and lifestyle hats, hoodies, tees, and more. They’re super soft, they’re a great fit, and they’re designed and printed in Denver, Colorado. Be sure to check out the new line of Hunter Angler Gardener Cook apparel, and use the promo code Hank10 for 10% off your first order. That’s Hank10, H-A-N-K 10 and you get 10% off any Hunter Angler Gardener Cook merchandise that you feel like picking up and wearing to your next event. Thanks.

So I did a little research on why we have them. The earliest recorded introduction of a Hungarian partridge was in the 1790s in New Jersey of all places. I mean, obviously New Jersey in 1790, it looked a lot different than it does now. But I’m from there, and there are places in the south of that state where I could see that you could have Huns there. And it didn’t take for probably the reason because they’re they do get cold but they have very, very wet springs and, and gray Partridge is primarily a step bird. It’s native to very arid, wide open spots.

So they tried it in Virginia in 1889 and then that failed. They tried it a whole bunch of other places, east of the Mississippi, like Michigan in 1910, Oregon in 1900 and that actually took because they put them in Eastern Oregon, which is exactly like a step. Then 1905 in Iowa, Minnesota in 1913 and the south western part of that state. So you started to get these good introductions starting at around 1893. I think they introduced something on the order of 200,000 birds as kind of the seed crop. Then now you can hunt them in 12 states.

Tyler Webster:

And some Canadian provinces, too.

Hank Shaw:

Right. The three plains provinces, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. The only place I know of where the entire state holds Huns is yours, is North Dakota.

Tyler Webster:

You can pretty much bisect the state of North Dakota in half, really, going north to south.

Hank Shaw:

Well, as a Dakotan, that the Dakotas were improperly divided. Probably North and South Dakota should be East and West Dakota.

Tyler Webster:

100% because there’s a huge difference between East and North Dakota, West and North Dakota, Eastern South Dakota and Western South Dakota. And it pretty much the Missouri River is the divider. So you can pretty much follow the Missouri River where it comes up through Bismarck and go straight north through mine and all the way to Canada. And if you go east, it’s flat agriculture, prairie pothole. If you go to the west though, it’s not very far to the west either, you start getting into a little bit more rolling country. And obviously down in the southwest part, you start getting into the badlands as well. But it becomes a little bit … There’s still plenty of agriculture in the West, don’t get me wrong, but there’s a lot of cattle production as well. It’s nice cattle country, there’s pastures and pieces of prairie that’s still virgin, never been broken prairie.

Hank Shaw:

I also got a chance to hunt sharp-tailed grouse on a piece of virgin prairie in North Dakota once. It was amazing.

Tyler Webster:

You come here next year and we’ll … I love chasing sharp-tails, too. Sharp-tails are my second favorite bird and it’s one and one B for me. They’re a fantastic bird. But right here by where I live, there’s lots of virgin prairie and where I’m at is it’s either the first or the second depending on the year as far as harvest of sharp-tailed grouse and always first or second for the harvest up Hungarian partridge in the state.

Hank Shaw:

Wow. You’re a lucky guy.

Tyler Webster:

I live in the right spot.

Hank Shaw:

Can you remember the first time you hunted Huns and what lit the fire for you?

Tyler Webster:

Well, I can. In fact, I know exactly where I shot my first one. It was that first season that I was hunting. I was eight years old. I was carrying a single shot 410. It was just a quarter mile north of the family homestead. So it’s still in the family. My best friend Mike lives there and farms for my uncle and my cousin now. They’d be the fourth generation farming that same piece of land. When I was growing up, we hunted birds but we did it kind of like you do, we were bushwhackers. I guess, it’d be a good way to put it. We didn’t have dogs, we walked them up. But we also spent a lot of time in the fall trapping fox and coyote.

This particular day, I had missed God knows how many birds by this time because this is October. But we saw this covey, we were driving down this prairie trail going to check traps actually, and we moved to covey upon off the prairie trail and they flew out to a rock pile about 100 yards away. My grandpa, he was probably only in his early 60s then, a very good shot. He shot a beautiful Browning Sweet Sixteen semi-automatic, that I still have. He put the truck in park and he’s like, “Tyler, grab your gun.” I said, “Okay.” We walked out there in this covey got up 10 yards, maybe. I was shooting 410 with eight shot and he was shooting 16 gauge with sixes. We had to do, what’s the right word? Necropsy, I guess, on the birds afterwards to figure out if I’d hit it or not.

And sure enough, one of the ones that had fallen was one that had H out of it. I think we got three. He only shot twice so he was pretty sure I got one. I was less sure than he was. I just knew that I’d shot once. But later on that evening when we’re cleaning birds, we did find little H pellets in one of them. That covey is still there. They’re always right there within … They’re descendants of that same covey that I was hunting then and he probably hunted them before that. We still go out there and chase them every once in a while.

Hank Shaw:

I wonder about that. In my own home turf in the Sierra Nevada, the California with the mountain quail, I wonder if some of those coveys are ancient. Having been there decades, even 100 years or more that occupy the same space.

Tyler Webster:

Sure. First of all, I was very flattered when you said that you talk to a lot of people and they said that I was one of the most Hun crazy people around. I got my fire from that. But I learned everything that I know about Huns from a man by the name of Ben Williams from Montana. He’s got a fantastic book called Huns and Hun Hunting. He’s got a story in there about what he calls the Keystone covey. In that book, he talks about hunting the same covey of Huns in the same farmstead for 50 years. They’re always in the same farmstead that he hunts. He goes there every year.

If they move ahead of him and his dogs, he doesn’t even shoot him hardly anymore. Ben’s in his 90’s, I think. Still out there. I think he still has 12 dogs. He’s just an insane man. But he said that having hunted them for as long as he has, when he moves them, he can almost tell where they’re going to go before they do. He knows them that well. He said that every year, you move them, they go to here and then you move them from there and they go to here. Then about the fourth time, you’re going to find them right back where you found them the first time. It’s built into their genetics, I suppose, from the escape routes from ancestors past, I would imagine. But, like we said earlier, who knows exactly what the makeup of all that is. It’s kind of romantic to think that it would be descendants of that same covey that he’s been hunting for 50 years, I guess. I kind of like to believe that.

Hank Shaw:

It’s pretty amazing. I mean, you hear about goose flocks and they’re all family groups. A big giant flock is a bunch of different family groups and so you definitely do have very long lived social birds. I think it’s a slightly different deal in the sense that you have long lived social birds whereas Hungarian partridge are short lived social birds, so there must be just a very … It sounds like their lives are stressed. They’re stress-y birds. When I’ve hunted them, they’ve always seemed super stress-y because of all the things that are trying to get them. I can imagine the mom and dad teaching their chicks like, “Okay, you go here. If anything goes there, you go there. If anything goes there, you go there.”

Tyler Webster:

If we get split up, we meet back here.

Hank Shaw:

Exactly.

Tyler Webster:

Yeah. I like to believe that. I mean, I know that there is at least some truth to that because, like I said, there’s coveys that I’ve been hunting myself for 15 plus years, and there are discernible patterns in where they’re going to head to. It’s like they have a pre-determined escape route that their parents probably showed them and their parents showed them and their parents showed them. But once you hunt them enough and you start figuring out their patterns, it can be really fun because when you’re taking people out there who don’t know these birds …

For example, I was walking not very long ago with a guy who had never hunted the spot, never actually hunted Huns before. I was like, “All right, so here’s the deal. We’re going to walk up this little draw and about a half mile up there on the left hand side, there’s a bush. Underneath that bush is going to be a covey of Huns.” And he’s like, “What?” I’m just like, “Just believe me. When you get up there, be ready because there’s going to be Huns there.” I said, “Watch your dog and just be ready.” He kind of looked at me like, “You’re full of it.” I was like, “Okay, well, you don’t have to believe me if you don’t want to, but I know that I’m going to be walking that direction.” He’s like, “Okay.”

Sure enough. We got up there, dog went on point. Covey of Huns gets up. He’s not paying any intention. They fly away and he’s like, “Oh my God, I can’t believe you’re right.” I was like, “I’ve been hunting these birds for a long time. I know where they’re going to be. For the last five years, the first time I hunt this particular draw every year, they’re always in this bush.” They can really make you look almost like a savant of some sort. He’s like, “How can you know that?” I said like, “Well, I’ve been doing this for a long time and I know these particular birds.”

Hank Shaw:

So if somebody is going to start hunting Hungarian partridges, if I live in the Dakotas, Nebraska, Iowa, Idaho, Nevada, wherever there’s a huntable population and I say, “Okay, I would just listen to this podcast, I need to get started doing this.” What would you tell someone who wants to get started pursuing these birds?

Tyler Webster:

Well, I tell them several things. I tell them to buy really good boots because you’re going to be walking a lot. When I mean a lot, an average day of Hun hunting in early October, which is my favorite time to chase them, is going to be between nine and 11 miles. Even in good years, this was a particularly good year, in fact, one of my statistically best years I’ve ever had. I keep track in a journal, you’re going to be … There’s a lot of distance between coveys. Like this year, if you put on a 10 mile day, you’re going to move close to a covey a mile on average. But just because you move them doesn’t mean you’re going to get on them. Eventually, they’re going to evade you. They’re going to lose you, they’re going to go behind the hill and disappear like they just seem to do. They just evaporate sometimes. It’s fascinating. So you need a really good pair of boots.

You need a big running dog. That is absolutely key. My dog’s tip, I have a little year and a half old English setter and this one right here next to me right now, she pointed to a covey of Huns, she was 400 yards away from me when she went on point. You need a dog that can cover some ground because they’re … If you want to think about a scent cone for a covey of Huns, it’s probably 20 feet wide by 30 yards long. We’re in a country that is enormous. And if you don’t have a dog that can get out there and actually range like that, you’re really putting yourself at a disadvantage to the point where you almost kind of have to get lucky to find them.

Well, listening to this podcast, hopefully some people will pick some tips. I haven’t chased a ton in other states so I guess, I can speak as sort of an authority on the birds that are in North Dakota. I do know a little bit of … I mean, what I’m saying is going to be correct in a general term but they’re a bird that likes edges. They thrive right where the prairie and the agriculture meet. I find lots of in the middle of a big wide open wheat fields or canola fields like I was talking about earlier but they’re still going to find an edge. It’s going to be the edge of a slew or a fence row or some sort of terrain change or a draw that goes through there. Those are going to be spots that are going to be priority spots. You will occasionally just find them out in the middle of pasture or out in the middle of a wheat field, but they’re generally going to be fairly close to some sort of an edge.

Hank Shaw:

There’s a lot of game birds that are like that.

Tyler Webster:

Right, right. So you can kind of eliminate a little bit of the country before you even start. Say, there’s a decent draw with some grass and bushes and stuff like that, that run through an agricultural field. That’s going to be a pretty high priority spot for me, that’s going to be a spot that I’m going to try to work on. At least push through there and see if the dogs get interested at all. Then also while I’m out there, I’m looking for different sign. When you get to those bushes, like I was referring to in those draws, if you look underneath them and you see a bunch of scratching or places where birds have dusted, there’s kind of like a little depression, loose dirt there.

Or, just like with quail, you’ll find a … Well, I mean, it’s a pile of poop is what it is, but I mean, it’s going to be very concentrated in a small area. That’s going to be one of their recall sites or one of the spots where the coveys spent time and they literally will just sit in one spot. So if you start seeing that, you know there’s birds in the country, then you’re really going to start trying to explore it a little bit further and seeing if you can locate them.

Hank Shaw:

This sounds a lot like Mearns quail hunting.

Tyler Webster:

It really is. It’s very similar. That’s why I’ve really, in the last couple of years, I’ve become really infatuated with Mearns quail because they’re like the Hungarian partridge of the South. They act very similar. I mean, if you can do those things, that’s a start. The other thing that a person needs to do is … The internet’s a wonderful tool, the Game and Fish in whatever state you’re looking in, they’re going to have some information on there on where the … Like I said, I mean, like in North Dakota, I know that they break it down with harvest reports based on counties. You’re going to want to spend a little bit of time and dig into the numbers a little bit and see which counties are the most birds being harvested in because obviously there’s going to be the more birds in those counties.

I wouldn’t go out on a limb and say that there’s probably at any given time in North Dakota, probably between one and five people that are actively out hunting Huns and the one is definitely me. They’re not a bird that many people focus on. They’re a bird that a lot of people shoot as almost as bycatch. They’ll be pheasant hunting or sharp-tail hunting. They’re kind of a bird of opportunity for most people. So when you-

Hank Shaw:

It’s a little weird when you consider it. Because we’re going to get into to the cooking and eating part at some point, but of every game bird that lives in North Dakota, I think with the possible exception of the prairie chicken, which I don’t think you can hunt anymore in North Dakota, the Huns is the best eating bird out there.

Tyler Webster:

I agree. I 100% agree. But there are people, there’s just a lack of … Okay. I’m going to say something that’s going to offend some people and I hope that nobody gets real pissed off.

Hank Shaw:

Because they’re fat, lazy, and they won’t [crosstalk 00:39:35]

Tyler Webster:

That’s exactly it. I’m fat, don’t get me wrong, but I’m not lazy. They’re a boot leather bird, you need to put on miles to find them. Then a lot of people, they’ll find them one time and they won’t pay attention to the … They won’t try to replicate that situation. So if I’m walking across a field and I started seeing a particular type of weed and all of a sudden a covey erupts, I’m looking at what that weed is. I’ll guarantee you that if I happen to see another patch, that I’m going to go and look. There’s patterns that people just don’t pay any attention to. So they’ll be walking all of a sudden, and covey goes up when they’re on their way to a cat tail so they go shoot pheasants or whatever, and they’ll shoot them and then they won’t pay any attention to where they found them at.

It really does come down to the fact that a lot of people nowadays are really lazy. And you’re not going to have one of those days where you can’t let … Like you can in here in North Dakota where you’re going to see 500 pheasants in a day. You’re not going to see 500 Huns in a day. I don’t care how many birds there are in the state, you just don’t have the time and there’s not enough hours in the day to walk far enough to see 500 Huns. If you can see 100 in a day, that is a fantastic day. And people just don’t really have a lot of time for that.

Hank Shaw:

If they’re on the east side of the river, they need to go watch either the Vikings or the Packers and if they’re on the west side of the river, they got to go see their Broncos.

Tyler Webster:

Pretty much. I’m on the west side of the river. I’m going to be watching the Vikings regardless. The Broncos, who cares?

Hank Shaw:

There’s quite a number of Western Dakotans who follow the Bronx.

Tyler Webster:

Well, they had last week go for them. They were up 20 to nothing. The Vikings still end up beating them.

Hank Shaw:

That’s kind of hilarious. Let’s talk a little bit about dogs. So I don’t hunt with a dog. That’s because I travel so much, I feel it would be unkind to the dog for me to actually have one. The other thing is I have so many different kinds of birds that I’m not entirely sure if I got a dog what kind of dog I would get. I mean, ultimately, if I do end up getting one, it will be a dog that haunts quail well, because that’s where I live. So you mentioned already a wide ranging dog. So beyond that.

Tyler Webster:

So you need to have a dog with manners. It’s going to be important because it doesn’t do any good for you to have a dog that will run 400 yards away from you if they won’t go point, right? If you don’t, it’s just going to become a rodeo. You’re going to be mad, you’re going to be yelling at your dog, it’s going to be really unpleasant for everybody that you’re hunting with. It’s going to be unpleasant for you, it’s going to be unpleasant for the dog. Huns are a bird that does not take pressure well. A dog has to be able to point them from distance. So you need a dog that …

My dogs, they grow up chasing these birds. So their first instinct is if they smell something, they’re going to stop. Whether it’s there right at that second or if it’s a little bit older since most birds have moved, that’s secondary for me and for them. Because they understand that if they smell it, they’re not real sure if it’s there or not, they err on the side of caution a little bit.

Hank Shaw:

What breed do you run?

Tyler Webster:

I got two different breeds. I got two English setters. Rusty is my oldest, he’s six. CJ is my youngest, she won’t be two until the first of February, I think. Then I have a German shorthair as well that’s just about two and a half.

Hank Shaw:

Okay. So you’ve got a wide ranging dog that has manners.

Tyler Webster:

Yep.

Hank Shaw:

I assume your pointers are pretty much the … You got to go with a pointer.

Tyler Webster:

Yeah. Well, I don’t think that they … If they do make a wide ranging flushing dog, it probably isn’t a good thing.

Hank Shaw:

I have seen them.

Tyler Webster:

I have, too, and it’s not a good thing.

Hank Shaw:

In fact, funny story. So I am in Colorado and we’re chasing Colombian sharp-tails. And a friend of a friend puts us on this spot where he thinks that there’s going to be Colombian sharp-tails. I’m like, “All right, cool.” So he and his new dog, let’s just call the dog Dipshit. So Dipshit and this guy are on the left and it’s a young dog and he’s like, “Dipshit’s a real energetic dog.” And so we’re on the right with our dogs. So we’re working this hill and we’re going up. And all of a sudden, Dipshit just decides, “Who wants to go for a run?” He goes carrying off into this field that’s right in front of us, maybe 200 yards and 60 Colombian sharp-tail grouse get up and fly away, never to be seen again.

Tyler Webster:

When sharp-tails get up, you don’t find them again. They’re gone.

Hank Shaw:

I was livid. Because this was dawn, dude. This was like 30 minutes after dawn and we did not get our sharp-tails until the sun was going down. We walked all day long.

Tyler Webster:

I do it a little bit [inaudible 00:44:59] people do with my dogs, I only put one of my dogs down at a time. Because that way, I can pay attention to them. I can watch their body language, I can make a correction if I need. By correction, I mean with a collar. My dogs know very few commands. There’s several that are important. “Whoa,” is very important, especially when you’re hunting wild birds like Huns or sharp-tails. I need them to stop if I tell them to stop and they do know that command. And they also need to know, “Here.” They need to know how to come back. No matter what it’s for, those are the two most important commands that I teach a dog and that’s really mostly it.

Other than that, I kind of let my dogs … I let the birds teach the dogs more than me. They’re going to learn more from the birds, at least a good smart well-bred dog is, than what a trainer can teach them. I’m a firm believer in that. I think birds make a bird dog, it’s not a dog that’s trainable. They have to learn from the birds themselves. They have to learn what the birds will take, what they won’t take. I got a pretty interesting anecdote about my young shorthair that I got right now. I got him almost a year ago, actually, as a giveaway from a friend of mine. My friend’s a breeder in [inaudible 00:46:26] just to the east to me a little ways. He sold this puppy as eight-week-old dog to a person who got into a car wreck and couldn’t hunt no more.

And so the guy gave him back to my friend, the breeder, with the hopes of just finding him a place to go where he could hunt. Well, my friend George has seven dogs already and he’s like, “I just don’t have time for another one.” He said, “I know you hunt more than anybody I know, would you take them?” And I said, “Yeah, I’ll give him a shot.” This dog was 14 months old. I don’t think he knew his name. I know for sure he’d never been outside. So I worked with him all last November, December, January, and I shot plenty of birds over him in North Dakota, Kansas, Arizona, everything from Mearns, quail, pheasants, Huns, some sharp-tails, but not many.

And then this summer, he went to a trainer over at Montana. A friend of mine named Todd Laner who put a really good foundation on him because he was kind of … He was behind the curve. He was almost two years old and he’d had no experience at all in the first year of his life. So I wanted to get him kind of caught up to where the rest of my dogs were. And when he came back in August up here, we have what we call a training season where you can go out and you can run on wild birds. So it’s going to be young sharp-tails and Huns and pheasants. Can’t carry a gun obviously, it’s basically like practice for the dogs.

Hank Shaw:

And the birds.

Tyler Webster:

And the birds too, yeah. It really is a little bit of that. So what we do is as soon as you move a bird, you get any kind of dog work on it, you get the hell out of the field. Basically, it’s like my scouting season. It’s very, very valuable for getting the dogs into shape, getting myself into somewhat less of a round shape, getting my legs a little bit warmed up. When you’re not paying attention to shooting anything, you can really pay attention just to the dog, and you can make the corrections at the appropriate time. The shorthair came back from the trainer, his name’s Bo. The dog, not the trainer. The trainer’s name is Todd. But Bo, he was struggling a little bit. He wanted to take one more step. He’d smell them, he’d stopped for a second, he’d want to take a step, he take a step and the bird would go.

And you could see, every time he’d start kind of moving it back just a little bit, and then he’d stand a little bit longer and stand a little bit longer and it came all the way down to opening day. Opening day this year was the 14th of September and he still wasn’t doing it right. It just seemed like he just couldn’t make himself … It was almost like he didn’t believe his nose. And opening day this year was like 85 degrees. So we hunted a little bit in the morning with my three dogs. I have a rotation that’s set in stone. I never vary from my rotation. I hunt my dog Rusty first, CJ second, Bo third. The rotation stays the same. So if CJ finishes one day, Bo gets the first on the next. It’s the only fair way to do it, in my mind.

Bo is the last dog to go. We had to wait until about 5:30, six o’clock in the afternoon and I had one spot that I wanted to go and chase Huns in. We’ve been chasing sharp-tails during the morning. This dog literally hadn’t done anything right during the training season. I mean, he found birds but he flushed them. I mean, whether it was within range or not, it’s inconsequential to me. I mean, he hadn’t put it all together yet. So we’re walking across this field towards this little draw that’s kind of run through this egg field and it’s got a, the draws got nice brush in it. This covey of Huns kind of flushed really wild for whatever reason. I don’t know if they were just going back to cover after they were done feeding or if they saw us or hurt us or whatever it was. Usually opening day, they don’t do that.

Anyways, they went into this spot, just past this big cottonwood tree. And I watched the short hair. He was kind of working, working, working and he’s probably 200 yards ahead of me and all of a sudden he locks up. I have some friends up from Michigan that were up here to hunt. I mean, they were hunting sharp-tails but they wanted to shoot some Huns and I was like, “Oh God, this dog is going to screw this up.” I watched this young dog, he slammed on point and he never moved a muscle. I mean, not a single muscle. We’re walking up and two deer get up in front of him, take off running, and I was like, “Was he really pointing deer?” We saw those Huns go in there. There’s no way that he stood through those two deer running. I just knew that dog wouldn’t do that.

So he stood there and then the other guy’s dog got in front of him and went on point and Bo never moved. Then we walked 20 yards past him and he never moved and a covey of Huns went up and we shot five out of the covey and he went retrieved all the birds. It was like a game time moment where he’s like, “I know what I have to do. I’m going to stand here, I’m not going to move. If the birds go, they go, but I’m not taking one more step.” The instance …

Hank Shaw:

I was going to ask you that. I was going to ask you because a lot of times, especially with chukars, you’ll get a dog that will go on point and then the birds will run away. So you’ll get up to the dog and then the dog will have to re-establish a point because [inaudible 00:51:50] 100 yards. Do Huns do the same thing?

Tyler Webster:

Huns will move a little bit. A long ways for Huns to move is probably 50 yards. Their defense mechanism is not running like pheasants or chukars. Their defense mechanism is going up in a massive ball and in the confusion, getting away. Their number one defense mechanism is that. They will move a little bit but it’s not going to be very far. So if you see where they go down at and you get up there, if they didn’t re-flush and fly away, they’re going to be in that area really, really close. I mean 30 yards is a really long ways for them to run, really.

Hank Shaw:

Got you. So as far as a shotgun is concerned, you pretty much want to shoot at 10 gauge with number nines, right?

Tyler Webster:

Pretty much. Three and a half is nine shot. That’d be the best. [crosstalk 00:52:41] open choke.

Hank Shaw:

It’s probably open choke.

Tyler Webster:

I shoot a semi-automatic 20 gauge. I’ve never liked double guns. And I know there’s a lot of people out there that will shame me but screw them. I’ve always shot semi-automatics well and I like them to carry. So I shoot a semi-automatic 20 gauge and I move on my shot size through the years. So for starters, opening weekend, I’m shooting seven and a half low base, a good low base shell and I’m shooting improved cylinder for choke. As the season goes on and the birds get a little touch more wild and they start getting a little bit more plumage and denser feathers and they start feathering up for the cold weather, I start moving to sixes. I’ll go from shooting seven and a half’s and improve cylinder to sixes and a modified.

I’ve never shoot anything tighter than a modified. I think that full choke is water fall choke. If I can’t shoot them with a modified, then I don’t need to be shooting at them. But they will take a little bit more punishment than say even a sharp-tail will. Sharp-tails, they have a way of like if you hit them with a pellet in the toe, they’ll just lay over and die or wait for you to come up and kill them.

Hank Shaw:

[inaudible 00:54:02] do that, too.

Tyler Webster:

Yeah. Huns are a little bit more like pheasants in that respect, where they take a little bit of punishment to bring them down and then when they do get down, if they’re not dead, they’re not going to sit there and wait for you to come and find them. They’re gone. They’ll run when they’re wounded. Yeah, absolutely. You need to get out there as fast as you possibly can and get a dog there if you don’t think it’s dead. The other thing that happens occasionally on the covey rise is you’ll shoot multiple birds and then you’ll kind of lose track of where they are or how many birds come down. Because there’s so much confusion, everybody’s like, “I got two, I got two, I got two,” and there’s only like four birds that went down because everybody shot the same two birds.

Hank Shaw:

But at the end, it’s scar face then.

Tyler Webster:

Yeah, and it does happen. So I carry these little, they’re pieces of orange flag with a clip on them. And when I walk up, I put that orange flag with a clip on the first spot that I find the first bird or where I think that first bird went down, just to give me a place of reference, and then I start working out from there. Shot guns, 20 gauge, modified or improved cylinder. You never really have to shoot anything bigger than sixes. A good ounce of shot out of a 20 gauge is pretty good medicine for Huns.

Hank Shaw:

I would not have guessed that you would have necessarily needed to go down to sixes. But I found that that was very similar too where if you shoot doves, you’re shooting eights and sevens. But if you shoot pigeons, you need fives and sixes. Because a pigeon is a much, much meaner, doubter, tougher bird than a dove is. It sounds like the Hun is kind of like the armored quail because quail go down pretty easy, too.

Tyler Webster:

Yeah, they do. I think that they just get a little bit more densely feathered. So they live in a little bit touch colder climate.

Hank Shaw:

It makes sense. I mean, they can snow nest.

Tyler Webster:

Absolutely.

Hank Shaw:

Bobwhites and pheasants can’t snow nest, but these guys can snow … They’re the only introduced bird that can snow nest.

Tyler Webster:

Right. And you’ll see them January, February. You’ll be driving around and you’ll look out in the field and they’ll just be literally a basketball sized flock of Huns where there’s 15 of them and they’re … Just Google what snow nesting is if you haven’t seen, it’s really cool. They’ll actually rotate. The ones in the middle will get out to the outside edges and it’s a really cool process.

Hank Shaw:

Just like the penguins on the TV show.

Tyler Webster:

Kind of. They do take some punishment. The other reason I shoot six is I used to start shooting sixes about the first of October and shoot them pretty much through the rest of the fall. But once October gets here, I’m not just hunting Huns, I will also likely find sharp-tails on the walk, I’ll also likely find pheasants on the same walk. So when I’m out there, a stick … I’m a little bit of a shell snob these days. I shoot Prairie Storm sixes exclusively from October 1st. I think, that they put more birds on the ground where they hit the ground compared to a wounded bird. But whatever kind of premium shell you shoot, it does make a difference.

Hank Shaw:

I shoot Prairie Storm a lot, too.

Tyler Webster:

I like it. I mean, it kills them. The number of birds that are dead where they fell is way greater than they are with the cheaper crappy shells. Shells are the cheapest part of a hunting trip. You’re not going to Argentina and shooting cases and cases and cases of Prairie storm at doves. But if you’re going to go on a trip to North Dakota, bring four boxes of shells and just splurge and spend the extra $10 a box, it’ll be worth it.

Hank Shaw:

I was just on a sea duck hunt. And a buddy of mine brought these Boss shells from Michigan and they were two and three quarter super high base number finds in Bismuth. That was money on these birds.

Tyler Webster:

I shot a couple of them this fall. One of my friends from Wyoming, West Larrabee, was shooting Boss shells. Actually, it was the opening day of pheasant season this year. And we were hunting in a blizzard. It was weird. It was a very abnormal October, it’s very wet. But we took off right from my house. We didn’t drive anywhere. I think there were six of us. We just made it like a four mile loop right around my farm here and I didn’t bring enough shells because there was not a lot of birds. I ran out of my Prairie Storm and I had to borrow some of those Boss 20 gauge shells from him because he was the other one shooting 20 gauge. This rooster got up out of this bush at 50 yards and I just stoned him with those Boss shells and I was like, “Wow, these are decent.”

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, I was a believer. I mean, I whacked a blue bill at 50 yards as a kind of an open field tackle and I like it, okay. All right.

Tyler Webster:

You and I might need to start talking to Boss about a sponsorship. [inaudible 00:59:11] some free shells.

Hank Shaw:

So what are the gear do … I was just wearing blue jeans, boots and I mean, I wear that little Filson web vest because I’m usually hunting or …

Tyler Webster:

In warm weather.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, I’m usually hunting in the warm weather. So other than that, you don’t need brush pants. I mean, I know …

Tyler Webster:

No, you really don’t. If you’re hunting in a spot where you need chaps or brush pants, you’re probably hunting in the wrong spot for Huns. It’s probably too think and too nasty. When I was talking about the opening weekend this year in September and that group of guys that was up here, there was actually … The group of guys was actually Brent Pike from Pike Gear. He brought me up a pair of his new Pike Gear Kiowa hunting pants. They’re super lightweight.

Hank Shaw:

[inaudible 01:00:00] Dickies?

Tyler Webster:

I used to buy those Dickies or cheap Scheels Outfitters or Cabela’s pants or whatever and they’re tight in the thighs and are uncomfortable and they always rip, always. Every single time. I’d go through five pairs a year because in this part of the world, we cross a lot of barbed wire fences and when you’re fat, you can’t get over them very easily. You end up snagging the crotch on them and tearing the crotch out.

Hank Shaw:

I get nimble, man.

Tyler Webster:

I know, right? I mean, I’m nimble enough to walk nine, 12, 14 miles a day but …

Hank Shaw:

That’s not nimble. That’s just belligerent.

Tyler Webster:

That’s just me being stubborn is exactly what that is. But these new Pike gear pants, I actually say that they’re, it’s almost like wearing a pair of poplin yoga pants. They’re super comfortable and they’re very flexible and they dry really quick so I recommend them or at least take a look at them anyways. I’m not sponsored by them or anything else, I just really like this shit. Like I mentioned, a really good pair of boots. There’s a million different boot companies out there but you need something that’s lightweight. The best time of the year to have Huns, in my opinion, is right around the first of October so it shouldn’t be super, super hot. But you’re going to want a really good pair of lightweight boots.

I wear the Q5 Centerfire vest. Dan Priest makes out of Arizona. They really market it as a bird hunter’s daypack, really is what it is. I carry it because I can carry a lot of water. Up here, we do have quite a bit of water around. It’s most least safe for dogs to drink. We do have some concerns about blue algae some years, so you need to be a little bit careful. But even in October, usually the first week of October, I suppose the average temperature is probably about 60, 65 maybe, but it’s really quite comfortable to walk in.

But when you’re walking miles and miles and miles like that, for every one mile I walk, I figured that my dogs probably put on five to 10. So if I’m going to put on 10 miles a day, they’re probably going to go close to 70, 100, 50 at least. So you need to be able to carry enough water to keep them hydrated so they don’t get heatstroke and you get yourself into some trouble. So that’s really important, is to have a vest so you can carry enough water in. As far as other gear goes, you really don’t need a ton.

Hank Shaw:

I mean, it’s mostly like snacks, ammo, and a hat.

Tyler Webster:

Right. And then beer for the night.

Hank Shaw:

While you’re sitting in the truck and it depends on the season. So if it’s in September, you want some Hamms or like a Coors Light or something.

Tyler Webster:

Coors Light, yeah. Something nice and white.

Hank Shaw:

And then as soon as it gets colder, you’re moving to better beers and then finally …

Tyler Webster:

With scotch.

Hank Shaw:

That’s a December hunt. So speaking of scotch and things to drink, how do you eat your Hungarian Partridge?

Tyler Webster:

Well, you can make them a million different ways and pretty much any way that you’re going to prepare them is going to be good. I am not a world renowned wild game chef but some people are. I don’t even play one on TV or on the radio. I save everything off the ones that I possibly can but gizzards are fantastic. I always have a bag of gizzards floating around somewhere.

Hank Shaw:

How do you cook it?

Tyler Webster:

The gizzards? I just bread them and deep fry them. They’re fantastic.

Hank Shaw:

You’re so North country. First time I ever saw that, apparently they do it the South, too. But the first time I ever saw that I was in Choteau, Montana. I was with my friend Tim and we were deer hunting. This is the night before. We had just pretty much almost died because I was driving my … I used to have a Toyota Tacoma and so it’s a blizzard, and I’m driving up over an overpass and there’s a dually coming down the overpass as I’m going up. I thought, “I should slow down a little bit.” So I just go … On the brakes and the Tacoma goes broadside of the dually.

I can see the sweat on that guy’s forehead as I go right in front of the dually, we go over the overpass. And I remember saying to my friend Tim, “This is it.” He’s like, “Ah.” It’s like that scene from Planes, Trains and Automobiles. But I managed to steer the truck between the fence posts and go through the barbed wire and go boom, boom, boom, boom, and we’d land to stop at a disk field. Coffees everywhere. I look at him, he looks at me and then we listen to the truck and we get out of the truck and it seems okay.

Yes, seriously. I guess we’re okay. So we got back in the truck, got out of the field, because it was a four-wheel drive, thank God, and then went right to the bar. It’s like, “We’re not going to hunt deer right now. That was a sign.” So we got, of course, a couple of Budweisers when we got in there, and then the first thing we saw on the menu was fried gizzards and red beer. Like, “Wow, we are not in Kansas anymore.”

Tyler Webster:

Well, you probably could find that in Kansas, too, but …

Hank Shaw:

You could, actually.

Tyler Webster:

Deep fried gizzards are fantastic. Hearts, you can, I mean, same thing with … I don’t think you can mess up hearts or gizzards, to be real honest. There’s a lot of people that don’t save them and it’s really kind of a shame. People don’t know how to clean gizzards, which are really kind of a nice little treasure inside that little bird. I save them out of sharp-tails, I’d save them out of pheasants and ….

Hank Shaw:

I say not every bird because I mean, here’s a case in point, a snow goose. Pulling gizzard out of a snow goose and hold it in one hand. Now hold the [crosstalk 01:05:51] in the other hand, they’re the same weight.

Tyler Webster:

Really? I’ve never pulled the gizzards out of a goose. I don’t hunt a ton of waterfowl, I’m more chasing upland. But I believe it.

Hank Shaw:

Do you pick your birds or do you just skin them all?

Tyler Webster:

I’m guilty of skinning. Huns would actually be … In fact, I have three of them out in the garage right now that I’m aging a little bit. I should try it on them. I bet they have pretty nice fat on them actually. A lot of times, they’re pretty plump little birds and I bet their skin’s really good. I’ve never done it before. So one of my favorite things to do with them is once you get the breasts out, I take all my legs and I put them in a bag and I got my leg bag out in the freezer. I just keep on adding to it over the year.

Hank Shaw:

I do that [inaudible 01:06:44].

Tyler Webster:

Yeah. But with the breast, one of my favorite things to do is just marinate them in a lemon pepper marinade for 40 minutes or whatever. And in fact, I’ll actually put them on a really hot grill and just grill them on each side for literally like a minute and then cut and slice them up decently thin and put them on top of a salad, almost like a chicken salad with some apples and cashews and walnuts and black olives and everything else. That’s really good. But you can really do pretty much anything with Huns that you’d want to do with chicken or pheasant or whatever. I mean, whether it’s sandwiches or … I mean, God, there’s so many recipes. I put them in a crock pot occasionally and shred them up and make barbecued sandwiches out of them. That’s fantastic.

Hank Shaw:

Should I tell you my story about crock potted pheasant?

Tyler Webster:

Sure. I’m all ears.

Hank Shaw:

This is not in North Dakota. This is in South Dakota. We were at a media hunt and these very, very nice people wanted to do like a special pheasant meal for the end of this trip. And we’re like, “Oh, yeah. Cool.” So what they ended up doing was throwing a bunch of skinned pheasants in a crock pot with cream of mushroom soup until they dissolved. Basically, we were served the whole pheasant partially melted in a brown stuff. It looked almost exactly like the last scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark where their faces are melting. We dubbed that Pheasant Apocalypse. Please, don’t ever do that with any bird ever.

Tyler Webster:

I love my crock pot. In fact, right now, I got two deer roasts and potatoes and carrots in a crock pot right behind me.

Hank Shaw:

Much better use. Let me tell you about plucking Huns. So I know a bit about working with Huns from the ones that I’ve gotten from Montana. So, readers or listeners, readers of Hunter Angler Gardener Cooker, listeners to this podcast will know that the trick with all upland birds is to let them sit whole and in the feathers for three days. You can do two but the worst time to pick an upland bird is when everybody wants to pick an upland bird, which is to say the night after the hunt or the morning after the hunt. The feather stick like glue in that period. Even I have a hard time picking them and I’m very good at it.

After 48 to 72 hours … You can let them go even a little bit more if it’s cool, obviously, you live in a cool place, the feathers relax and they will come out easier. The trick is just it’s all finesse. Everything about plucking an upland bird is finesse. You can actually manhandle a duck and the skin is so thick that you’ll be okay.

Tyler Webster:

I believe that.

Hank Shaw:

You can’t manhandle anything upland. Especially the smaller gallinaceous chicken like birds like a Hun or a quail or a chuckar. So they have two different kinds of feathers, there’s the little teeny under feathers and then there’s the display feathers that make them look pretty. So all of those feathers that make them look pretty, typically it’s on the left and right edge of the breast, then it’s the flank feathers. Imagine if you were a bird, it would be like where your jeans pockets are. So those are places where it’s going to rip. The side of the breast is where it’s going to rip. And then the neck is where it’s going to rip because the neck has …

If you grit your teeth like that, the kind of the veins or the tendons stick out on your neck, well, the bird has the exact same thing. Where the tendons stick out when you grit your teeth is the same structure that a Hungarian partridge or really, any gallinaceous bird is going to have, that’s going to be the feathers that’ll rip. So in between the high points are the darker, easier feathers. The way that you pick any bird, there’s a lot of Zen to it. You have to be calm, you have to pay attention, you have to … You can’t rush it. You can make it go quickly but a lot of this is being nimble with your fingers. And a lot of times, you’re picking one feather at a time. You can go pick, pick, pick, pick, pick but it’s still one or two feathers at a time.

The biggest mistake everybody makes is to grab four or five feathers and try to pluck and then you’re just going to ruin it. And always work with an ungutted bird because if you have a gutted bird … The exception is a wild turkey because of thermal inertia, but that’s another story. But for these small birds, they don’t stay warm that much and you’re going to be fine especially if they’re in refrigerator. The surface tension of the skin and you use your off finger finger a lot of times to keep the surface tension on the skin to pick that bird, once you get it, you can …

I mean, just follow my Instagram feed. I mean, I will take a picture of more or less every pluck bird I take to show people that it can be done. Once you get the hang of it, you’re … Basically, you’re welcome. Like you’re going to talk to me in a year and you’re like, “Oh my God. I thought I loved Hungarian partridge and now I really love Hungarian partridge.” The difference between them is this. Have you ever had a rough grouse with a skin on?

Tyler Webster:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah, it’s fantastic.

Hank Shaw:

It’s funky and fantastic and amazing.

Tyler Webster:

It tastes nutty, almost.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah. If you take the skin off, it’s like, “That’s okay.” Same deal with a pheasant. A three or four or five day old pheasant that’s been plucked and cooked is amazing. A fresh pheasant is a boring chicken.

Tyler Webster:

Yeah. And also fresh pheasants … I age all my birds and I’ve been doing it for several years for many reasons, but part of it’s because there’s a little bit of me that’s kind of lazy. I don’t really want to clean birds.

Hank Shaw:

It’s a good lazy.

Tyler Webster:

It really is. I got an aging table in my garage. This time of the year, my garage stays about 40 degrees. I have nine roosters and three Huns in there right now that have been aging for about four days and tomorrow I’m going to clean them. But the difference that you’ll notice just in the toughness and the, well, I guess it’d be the tenderness of the meat by aging them seems to, it’s night and day difference. If you clean them the day that you shoot them compared to four days later, it’s a totally different piece of meat.

Hank Shaw:

It really is. It’s dramatic. I mean, one way to you can tell, and I’ll put a picture of this up in the show notes of this episode is you could put a fresh picked pheasant … Pheasant’s probably your best example because everybody has access to them. A fresh pick pheasant and the legs are going to stick up in the air. A four day or five day or six day old pheasant picked, the legs are going to rest like you would see on a chicken in the supermarket. Everything is relaxed. You’re still not going to … I mean with a pheasant, you’re still going to have to deal with the tendons and the legs because they’re running birds. Cool thing about Huns, like I said before, they don’t run so much.

Tyler Webster:

But thighs, specifically in Huns are fantastic.

Hank Shaw:

Oh my God. Of course, they are. I mean, it’s just the partridge recipes, so if you’re looking for inspiration … I mean, obviously Hungary because they’re from Hungary but look for, really, any European partnered recipes. So the English have them, the Spanish haven’t although the Spanish recipes, really they’re dealing with chukars but they’re interchangeable in the kitchen. There are slight differences in flavor between chukars and Huns but they’re mostly, on the basis of diet, there is no reason you couldn’t use a chukar recipe or really a quail recipe for Hungarian partridge. They’re within three or four ounces of each other, no matter what kind of bird you’re taking.

Tyler Webster:

I’m starting to experiment a little bit more with cooking. When I was growing up, pretty much everybody from this part of the world, all the wild game was always cooked well done. It was usually put in some sort of gravy or something. Nowadays, I can’t even … My grandma still likes to make a country gravy with birds in it and put it over … I can’t do that anymore. It’s fine …

Hank Shaw:

I’m going to defend your grandma actually. A squirrel gravy, like the old school squirrel gravy, I mean, there’s a place for that. I mean, artfully done, slow cooked pulled meat with a broth made from that animal turned into an amazing gravy, all put over grits or up in your part of the world, mashed potatoes or even just served with bread, that’s damn good. But everybody who is listening to this has had a really horrendous version of that.

Tyler Webster:

Sure. I mean my grandma’s cooking is great but there are a lot better uses of a lot of these birds. I mean, if you want to do that with pheasants, by all means. But pheasants to me are just they’re kind of like the fowl version of walleye. Yes, it’s fantastic, but it’s going to taste exactly whatever you season it with. I don’t think there’s any real taste of pheasants. It tastes a lot, like you said, like a boring chicken. When you get into the darker meats, Huns aren’t dark, dark meat, but they’re somewhere in the middle. They’re not white meat like a pheasant, they’re not dark meat like a sharp-tail. But there’s so much better uses of that kind of meat than putting it into gravy. You can cook it medium rare and literally just eat it like a piece of meat. I mean, it tastes fine. It’s great. You can do any kind of like a stir fry or whatever. There’s so many different things that you can do with it without having to cook it for hours in the oven and gravy.

Hank Shaw:

I mean, one of the cool things about these birds is that they don’t live very long. So that does give you the opportunity to treat them much like a cottontail, in a sense. Hungarian partridge and chukars and quail and cottontails are really some of the only wild game that you can chicken fry. I don’t know, I don’t care who you are, fried chicken is amazing if it’s [crosstalk 01:17:51]. Really good fried partridge? It’s to die for.

Tyler Webster:

Yeah. When our mutual friend Janno Doe was up here earlier this year, he got pretty preoccupied with picking a bunch of choke cherries and it got me thinking about trying to make [crosstalk 01:18:09]

Hank Shaw:

As it should?

Tyler Webster:

Yeah. It got me really excited about making some sort of like … All the way until you come up next year and you can teach me the ways. But making some sort of like a choke cherry sauce to put over top of the Huns I think would be a pretty nice pairing.

Hank Shaw:

I’ll walk you through it right now. So Sean Sherman, he’s known as the sous chef, I actually interviewed him in season one of this podcast. He’s from the Oglala Sioux reservation but he’s a great chef. I met him in Montana when I was on book tour in 2011 for Hunt, Gather, Cook, my first cookbook. And one of the dishes that he did, he had a choke cherry sauce and it’s super easy. As you know, choke cherries have a big pit in them. So you need a food mill or some way to separate the flesh from the pits. I do it in a food mill. So what you do is you take your choke cherries and you put them in a pot and you just barely cover them with water. So you almost don’t cover them with water, you need a little bit of extra water in there.

Bring it to a boil, turn off the heat, let it come back to room temperature. Run that through a food mill and then that’ll loosen all the meat off the pit and then you’ll get all of the good stuff in the bowl underneath the food mill. And then from there, you can do any number of things. If you want a super clear sauce, you want to get chef-y with it, then you run it through a fine mesh strainer and da, da, da. But if you don’t, one cool thing is to just add sugar to taste because it can be super sour. And my advice, if you’re going to make a sauce for a Hungarian partridge or any other bird, is you add a little bit of sugar and salt so you make it kind of salty savory. You have to go a little bit by a little bit and only you are going to know when it’s right. Then buzz that in a blender hard and it will stay emulsified for your meal.