As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

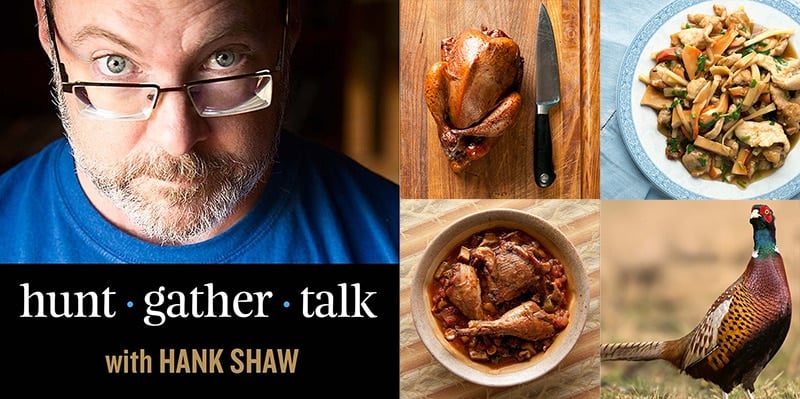

In this episode of the podcast, we’re talking all about pheasants and pheasant hunting, with two good friends of mine: Bob St. Pierre of Pheasants Forever, and the guy who got me into hunting almost 20 years ago, Chris Niskanen.

Every episode of Hunt Gather Talk digs deep into the life, habits, hunting, lore, myth and of course prepping and cooking of a particular animal. Expect episodes on pheasants, rabbits, every species of quail, every species of grouse, wild turkeys, rails, woodcock, pigeons and doves, and huns. Thanks go out to Filson and Hunt to Eat for sponsoring the show!

I’ve hunted pheasants with both Bob and Niskie, and we talk in depth about the history of this bird in America, its conservation status, how to hunt them both with and without a dog, which sort of dog works better for pheasants, where to hunt them, and of course how to cook them.

For more information on these topics, here are some helpful links:

- A good overview about the biology of the pheasant, from Cornell University.

- A primer on how to hunt pheasants by Project Upland with a dog… and without a dog.

- The story of my sharp-tailed grouse hunt with Niskie that we refer to in the show.

- How to hang pheasants safely.

Recipes

- You can find all my pheasant recipes here.

- But start with simple roast pheasant.

- Here’s the dirty rice recipe we mention, and here is the General Tso’s pheasant recipe we all love.

A Request

I am bringing back Hunt Gather Talk with the hopes that your generosity can help keep it going season after season. Think of this like public radio, only with hunting and fishing and wild food and stuff. No, this won’t be a “pay-to-play” podcast, so you don’t necessarily have to chip in. But I am asking you to consider it. Every little bit helps to pay for editing, servers, and, frankly to keep the lights on here. Thanks in advance for whatever you can contribute!

Subscribe

You can find an archive of all my episodes here, and you can subscribe to the podcast here via RSS.

Subscribe via iTunes and Stitcher here.

Transcript

As a service to those with hearing issues, or for anyone who would rather read our conversation than hear it, here is the transcript of the show. Enjoy!

Hank Shaw: Welcome, welcome back to the Hunt Gather Talk Podcast. Chris Niskanen and Bob St. Pierre, this is one of the rare instances, where not only do I know both of you guys, but I’ve hunted with both of you guys. And it’s maybe one of the very few podcasts where I have actual long-term good friends. So this is going to be a fun show, I think, or at least I hope. Welcome to the show. Chris, tell me a little bit about what you do, because up until recently, you worked for Minnesota D N R, and you are in a new situation now, aren’t you?

Chris Niskanen: Hey, Hank. Yeah. Chris here. Yeah, I was the communication’s director for the Department of Natural Resources for about 10 years. And decided I just wanted to try a new path in my life. I’m really interested in food sustainability and staying in communications, climate change and I’m employed at the moment, and looking forward to going hunting with Bob and Matt tomorrow morning at 6:00 AM.

Hank Shaw: We’re going to talk about our imminent hunting plans, because we’re going to pass like ships in the night in the Dakotas very soon. So Bob St. Pierre, I think most people know that you are the genius behind Pheasants Forever.

Bob St. Pierre: Well, it’s already going to get thick here, isn’t it?

Hank Shaw: You’ve been working at… You’re a vice president for communications, is that what it is?

Bob St. Pierre: Yep. Yeah, vice president for marketing and communications. I started working here with Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever when I was two, so 18 years later I’m now in my twenties, right Hank?

Hank Shaw: Yeah, you look good for 74.

Bob St. Pierre: So yeah, I’ve been with the organization since 2003. My role includes marketing the organization at a national level, membership recruitment, social media, media relations, our publications, as well as corporate partnerships, the National Pheasant Fest & Quail Classic. I was trying to remember exactly where you and I first connected. I got to believe it’s, when you follow the string all the way back to inception, it was National Pheasant Fest & Quail Classic, probably more than a decade ago. Do you remember better than I do?

Hank Shaw: I do. I remember the place. It was at the, I can’t remember the exact name of it but you guys will know, it’s the old school bar in Saint Paul that serves the really good fried walleye, and they served it to Gorbachev.

Bob St. Pierre: Huh. Is it Tavern on Grand?

Hank Shaw: I think, yes, I think it’s Tavern on Grand.

Bob St. Pierre: Okay.

Hank Shaw: We had lunch there. It was you and me and the Ray Han. And we all know, because Ray Han is probably listening to this, is Ray Han, Nana, which is, he now works for Garmin, but he is also an inveterate quail Hunter actually. And I’m going to have to chase those birds down in Missouri with him. But yeah, that was just a lunch meeting. And I don’t remember the year. I’m pretty sure I was already living in California at the time. And I think it might have been when I was on book tour in 2011.

Bob St. Pierre: That makes sense. Because the first time you appeared on a National Pheasant Fest and Quote classic stage was in Kansas city, which our first trip to Kansas city was 2012, because I remember talking to you about, you got any barbecue recipes to go with pheasant for the Kansas city stage? And so 2011, as we were planning that, makes a ton of sense. Time flies, doesn’t it?

Hank Shaw: Yeah, it has. It has. And so Chris, you sold yourself short a little bit, so yeah, I actually didn’t know you’d been working at D N R for 10 years. It seems like it’s only been a couple, but Chris is an outdoor writer of the Old School Order. He has worked as an outdoor writer off and on for basically your whole career, right?

Chris Niskanen: Yeah. Actually my first outdoor writing, outdoor writer job was in 1988. Went to the university of Minnesota journalism school and got an article published in fins and feathers magazine, which is kind of what started my whole journalism career. Decided I never wanted to ever cover a school board meeting or a city council meeting in my life. So 23 years later, I had accomplished that. Worked for three different newspapers, including the Reno Gazette Journal, not just over the hill from you there, Hank, and then spent 17 years as the outdoor writer at the St. Paul Pioneer Press, which was a real gem of a job.

Hank Shaw: And that’s how we met. I tell this story over and over and over again because people always ask me, I’m just going to start right now because it’s the first time I’ve ever had you on the air, when I tell this damn story, which I’ve told for 4,000 billion times, because every person who interviews me is like, “well, so how’d you get involved in hunting?” The story, as I tell it is, so you and I were working together at the Pioneer Press and I was an investigative reporter, and you were the outdoor writer and we’d been fishing. Because I moved in late spring or early summer of 2001, I think. It could have been 2002, but I think it was 2001.

The fall came as it does, and you had started to hunt and you invited me on, of all things of puff pheasant hunt. So it was perfect for this episode, right? And it was a pheasant hunt in Aberdeen, with the greatest gun dog of all time Finn. And of course Bob’s going to argue, because Trammel is the second best gun dog of all times. And we went out and I always tell the great story, “So, you hadn’t shot a shotgun before, right?” “Nope, never shot a shotgun before in my life.” So Chris whips out this, I think it was a 12 gauge over under it. Might’ve been a 20 gauge over under I can’t, you probably still have it. And you threw up like milk jugs and like some field. I remember we parked some random spot. There’s some trees on the left, I’ll never forget the scene.

And we pulled out the gun and we loaded it and you throw up some milk jugs. I think two or three times I hit one. And you were like, all right, we’re good. I proceeded to not hit anything on that trip. But the story that I tell that really hooked me and created the monster, which is why, by the way, if any of you guys out there have the book, Pheasant Quail Cottontail, which is my latest book, and it’s the book that accompanies this podcast season, the dedication is to you, Chris. And it’s basically says short and simple, it’s all your fault.

Chris Niskanen: I’m blushing Hank, right now. I remember that day. Can I continue the story?

Hank Shaw: Yeah. Yeah.

Chris Niskanen: I remember that day because we went out to Sand Lake National Wildlife Refuge, and it’s only open, I think from mid December, to the end of the pheasant season. And it was a really hard day of hunting. It was cold and super windy, perhaps probably the worst pheasant hunting conditions you can be in. And you were a great sport and a great companion that day. Complained only mildly.

Hank Shaw: Oh yeah, because I got a cattail in my eyeballs. It was-

Chris Niskanen: And I’ve done that before, when you’re going through cattails and you get one underneath your glasses, is horrible. Your eyes are watering, the tough part of that day was, walking through deep snow and there were lots of pheasants back then. We had quite a few opportunities, but walking through deep snow and then trying to shoot a bird that’s coming out super fast and your hands are freezing. It’s also happens to be my favorite type of pheasant hunting, because it’s hard and that many people do it, but you were a great sport that day. We slept in a horrible, horrible motel, I think in Britton, South Dakota, and the next day got only worse. So yeah, thanks for going on that trip. And the rest is history, I guess

Hank Shaw: Well, there’s one more piece of that hunt that I’m never going to forget. And that is, so Chris is really super nice when he’s in a house, but if you’re actually hunting pheasants with Chris, he can be a little bit sort of drill Sergeanty. And I didn’t fully understand, because I don’t know anything about hunting at this point. So he’s like, keep up, keep up, don’t, keep up with me. And he’s walking super fast, right? And Finn, the dog, Finn is the lab. She was kind of coursing back and forth and back and forth and back and forth. And while we were walking in a line on this field, he’s like, keep up, keep up. Because what he knew that I didn’t know at the time, is that there’s any number of disco chickens running in front of us that we can’t see. And so Finn’s going, getting birdier and birdier and birdier .

Hank Shaw: And I even, I can tell as a never before hunted guy, like, Oh God, the dog is getting super excited. And we’re nearing the end of this field and this brurururur, like a billion roosters come up and Chris shoots one, I miss, of course, because I flock shot like duh. And so Chris dings one, right? And it hits the ground, at the end of the field and there’s no more cover. So this pheasant immediately jumps up and does the chicken dance, imagine like a really freaked out pheasant with its head up looking super nervous, running for its life because a black lab is chasing it.

So Finn is chasing it, Finn is chasing it, Finn is chasing it. And then there’s a rock, a big old rock probably about the size of, oh, I don’t know, I don’t know, two feet by two feet. And this pheasant runs around the rock and Finn chases it three times, it’s like cute Benny Hill theme music. And then finally Finn catches the pheasant and then the game was over. But I’ll never forget that scene of Finn the dog was a little slim black lab, chasing around this, [Benny Hill music] and finally grabs it. Grabs the pheasant and then there we go.

Chris Niskanen: It’s funny you remember that so well, because, first of all, you nailed it. I remember that field, it was really thin cover and we were coming to the end and we were just pushing everything to the end. And it was just going to be a complete mess because everything was going to come out at the same time. And when Finn hit that ground with that pheasant, chasing that around, it was a rock pile actually. It was fairly sizable rock pile.

I remember we stood there and we just watched the dog go around and around the rock pile chasing this pheasant. And I knew she would catch it sooner or later, but it was one of the things that I remember that I love about dogs is just, they never give up. They’ll go to the end of the day and then they’ll go to the next day and the third day, and if you have a really good pheasant dog, they understand the bird better than you do. I know Bob, you know what I’m talking about and I’m sure we’ll get to that somewhere down the road, but thanks for that memory, Hank, because that was a great day.

Bob St. Pierre: Well, this is Bob and I do want to just attack on one little bit, because obviously I wasn’t there for the origin story, but there’s another story that Chris wrote featuring Hank. And this is back in the Pioneer Press days. And it was a North Dakota sharp tail hunt that you two did together. And you wrote the story about the hunt and then later that day, I think it was rose hips, Hank harvested, and then created a sauce if I’m recalling correctly, that you’ve just cooked up a sharp tail dinner with the birds and the rose hips on the prairie. And the year had to have been in the 2000 and let’s say eight or nine range-

Chris Niskanen: Sounds about right.

Bob St. Pierre: And to me, so obviously I knew Chris as a Pioneer Press writer and I was the media relations person at Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever at the time, but I didn’t know Hank.

I don’t think that the Prairie to plate, knowing where your food comes from, sort of ethos had really gained momentum. And that story, that friendship, that hunt, the combination of using everything you harvested that day on the North Dakota Prairie was a watershed moment for me. It was something that I read, and it resonated and ultimately led to, a lot of the ways that I think about marketing to one of the audience, is that, you know what? We want to engage in conservation, it’s that quote unquote, foodie automate audience, the locavore audience, the prairie to plate audience that we want to be engaged in wildlife habitat, in conservation, through the connection that’s so natural to many of us.

And that’s the land, to the birds, to hunting, to what hits your plate. And we can date it back to all the Leopold and his comments about food. Food, not coming from the grocery store, it comes from the land. And that, I’d read Leopold and that resonated with me, but Chris Niskanen and Hank Shaw brought it home. So that, on behalf of a whole generation, thank you. That was a, that’s just a really, really life-changing story.

Chris Niskanen: That was, it’s a hell of a hunt too. That’s where I learned that sharp tail grouse really ought to be called top of the hill grouse. Because every single, there’s, gazillions of sharpies everywhere. It was pretty much limits all around, but you think about the Dakotas is not being super flat and yeah, apparently not. So every single time you’ll be walking, huffing and puffing up a hill, and you’d be pretty sure there’d be sharpies up there somewhere. But you knew, well, at least I figured it out pretty quickly that they’re not going to be at the front of the hill, they’re hearing you come up the hill, and they’re like, “I don’t know.” And they’re like, “I still don’t know.” And then as soon as your head breaks the top of the hill they’re like, “Oh my god, hairless monkeys.” And they fly. And so you got to get, you got to stop before your head breaks the top of the hill, catch your breath, because the evil chickens are going to be flying the second your head stops it.

Bob St. Pierre: I’ve never heard of compared with a Wizard of Oz voice before, but that’ll stay as Chris mentioned, we have a departure about 5:45 AM tomorrow morning to, we’re going to the Southern Dakota in search of sharpies. So, there’s still time for you to join us if you want Hank, but otherwise we’re, I’m going to have that soundtrack of hairless monkeys in the back of my head now.

Hank Shaw: I actually have a normal departure tomorrow and I’m driving the 2000 miles to go to North Dakota. And it’s going to take me a couple of days and I’m going to be hunting with the guy I did the Hungarian partridge episode with, was Tyler Webster. And I am hoping, hoping, hoping to actually shoot a bunch of Hungarian partridge for the first time ever. I have hunted them a few times and I find them maddening. And they’re, unless you get a bunch of cubbies and you’re on the right hand side, because, quick side note, Hungarian partridges flush like bobwhite quail, which is to say all at once, and it’s always windy where they live. So they’re going to tip one way or the other way. And if you’re on one side of the line, you get a shot. And if you’re on the other side of the line and you don’t get a shot. So they are delicious birds too, so I’m pretty stoked about that. And we’re going to be hunting sharpies too, and-

Chris Niskanen: TIS the season. Bob’s story reminds me of why pheasant hunting is one of my first true loves. And that is the pheasants are a maddening bird as well. And the act of pheasant hunting always for me was an act of storytelling. And it was, it’s the combination of the environment, the bird, your companions, and this part of America that is largely ignored the kind of the fly over part of America and the fields and the prairies. And you put all those things together, and you kind of mix it up and it’s a perfect recipe for great storytelling. So thanks Bob for remembering that story. And thanks Hank for being on some of those adventures, because as Hank, you know, a good story is only as good as the companions you have along with you.

Hank Shaw: Let’s start talking about the bird itself. So most people know that pheasants are not native to North America. If you didn’t know that, now you know. They’re native to Manchuria. They are a distant relative of the actual chicken, which is from Southeast Asia. And they are known by any number of names. I prefer disco chicken. Some people call, some people like ditch parrot, but they’re, they were brought here by the American ambassador to China in, I believe 1871.

Bob St. Pierre: 1892.

Hank Shaw: Okay. And they came over and they were first set down in the Willamette Valley in Oregon. And they did so well in Willamette Valley, Oregon, there was a hunting season very shortly thereafter. And this was a time where fishing game departments and societies and such were like, yeah, there’s this awesome game animal halfway across the world. Let’s just put it here and see what happens.

And they did that with a whole bunch of things. But what they found out is that the pheasant, actually liked it here and did quite well here. And the episode I did on Hungarian partridge was a story where that didn’t work. As you can guess by its name, a Hungarian partridge is not also native to the United States. They used to put them in upstate New York. But they didn’t do, they didn’t do very well at all where the pheasant did.

The other funny thing about, when you look at the books about wing shooting and upland hunting from the 1890s and early 1900s, you will see all kinds of hate raining down on the poor pheasant. Because all of these old school wing shooters, more than a century ago were used to things like rough grouse, quail especially, and other birds that are a bit more skittish and a bit more fast flying. So there’s like, well, yes, it’s a pedestrian bird that has gory in it’s looks and blah-blah-blah. So there is to this day, and it’s usually people from the Northeast who have patches on their elbows and smoke pipes, a looking down upon, on our beloved disco chicken. So Bob, defend the, how do you put it? The non-native slightly invasive-

Bob St. Pierre: Our beloved ring neck. And so I’ll correct myself, but so the very first attempted introduction was 1881. So you’re right. I was a slightly earlier. The very first hunting season was 1892. And the ring neck pheasant, I see it every day, whether it’s Twitter, Instagram, the trolls out there, kind of holding their noses up over this migrant species. But the reality is, the ring neck pheasant has captured the passion and the love of millions of bird hunting, conservationists. And has been the centerpiece of, it kind of a conservation movement across the native prairie. The bread basket of America, which Chris articulated earlier, fly over country. And we have habitat on the ground and we’re going to focus very specifically at the conservation reserve program, We’re presenting 27 million acres of habitat. [crosstalk 00:22:01]

Hank Shaw: So, stop you for a second.

Bob St. Pierre: Yeah.

Hank Shaw: Tell the listeners exactly what the C R P is. Because there’s a lot of people who don’t know what it is.

Bob St. Pierre: Yeah, yeah, so every say four to five years, the federal government creates what’s called, The Farm Bill. And the farm bill covers policy from food stamps, to crop insurance, to conservation and the signature program within the conservation title of the farm bill, is the conservation reserve program. Bird hunters know it as C R P. And it fluctuates in the total number of acres, you’re, based on the farm bill.

However, the moral of the story is, this program was created in 1985 under the Reagan administration. And has been re-authorized through every farm bill, through both Bush’s, Clinton, Obama, and now it’s under the Trump administration. And represents anywhere from 20 to 40 million acres of habitat based on the given farm bill. And it was originally created to kind of prop up commodity prices.

But very quickly, the government and land owners saw benefits for soil health, benefits for water quality, benefits for rural economies, oh, and all this habitat that’s created, generated tremendous wildlife population responses, chief among them, well, chief among them from my point of view are red necks pheasants. And so the habitat that’s been created through C R P benefits more than just pheasants though. It’s waterfall ducks, mule deer, pollinating insects, monarch butterflies, but the ring neck pheasant through the efforts of primarily bird hunters, duck in upland hunters has become sort of the signature component of C R P, which is, has the recognition as being America’s most effective conservation program.

Hank Shaw: All right. So let me stop you for again, for a second. I’m going to tell people what C R P actually is because you know too much about it.

Bob St. Pierre: Okay.

Hank Shaw: So C R P and you tell me if I’m wrong, is so it’s a federal program that says a landowner, typically a farmer, can set aside for, this is the reserve portion of the C and the R in the C R P, part of his or her land and not farm it because typically it’s going to be marginal land anyway, it’s not going to be your best ground to grow on. So you just let it be what it’s wants to be. And then in return, because the federal government has recognized that there are benefits to having this kind of fallow land. We’re really not messed with land. You get some money, so you’re, you’re compensated for it.

Bob St. Pierre: Yeah. So I think you’re accurate in the creation of C R P back in 85, where it was termed set aside and it had a passive approach. Over time, both the federal government, state governments and landowners, as well as conservation groups have taken a more active approach to C R P, where it’s not just, let it be what it wants to be. It’s very specifically, managing those acres that 100% right. It’s environmentally sensitive, it’s not the best farm land, but you can do prescribed burning on it, seeding it with pollinator mixes. So it doesn’t just become, after three or four years of being quote unquote set aside, become a monoculture.

Hank Shaw: Got you.

Bob St. Pierre: We really actively want to manage it as wildlife habitat that cleans water, that improves the health of soils and creates a place for a wide menagerie of wildlife species. So it has evolved since its 1985 beginnings.

Hank Shaw: So we’ve referred to it a number of times already in this podcast as the ring necked pheasants. So there are lots and lots and lots and lots of different kinds of pheasants. So does, do either of you know why the ring neck and not say the golden or the green or whatever, whatever? What’s special about the ring neck pheasant versus all the other varieties?

Bob St. Pierre: Silence, which means, I don’t know the answer to that. I grew up in Michigan in a time that the state of Michigan tried to introduce the Sichuan pheasant. State of Michigan tried to introduce the Sichuan pheasant to more wooded areas of the state of Michigan, because like many places the prairie’s were being taken over by more forestation because you really truly have to actively manage grasslands. That’s what the buffaloes did, that’s what fire on the prairie did and if you don’t actively manage, it becomes early successional forests. So Michigan had this idea to release session-one pheasants in the late ’80s and it failed miserably. Ultimately state of Michigan had money that… They saw that this wasn’t going to work and they took the rest of that budget and allocated it to Pheasants Forever to do habitat work as opposed to releasing any other Sichuan birds.

Just releasing birds in general, but session-one in particular is not an effective way of augmenting wild populations and in fact, it can become a very big detriment because you have the potential for introducing disease into a wild population. Just look at what’s happened with deer and CWD. The same thing could potentially happen with released pheasants and introducing an avian influenza into a wild population. So I’ve long-winded answers to, I don’t know a lick about the other species Hank. I know that when it comes to releasing birds with the ring-neck is the one that worked and habitat is the name of the game for keeping them here.

Hank Shaw: How about you Chris?

Chris Niskanen: Well let me just say, I want to ask Bob if he reconsidered renaming his organization Disco-Chickens Forever?

Bob St. Pierre: Ditch Parrots was considered-

Chris Niskanen: Ditch Parrots Forever.

Bob St. Pierre: Ditch Parrots Forever was considered, but DPF was not the acronym we wanted to run with.

Chris Niskanen: There’s a couple of other funny names, Stubble Ducks. You ever heard that one?

Hank Shaw: No, that’s a great one.

Chris Niskanen: I love Stubble Ducks, and Rudy is a good one. Now, I want to get an official ruling on this. I’ve heard pheasants called thunder-chickens, but I’ve also heard ruffed grouse called thunder-chickens, Bob-

Hank Shaw: Turkeys are thunder-chickens. If you use thunder-chicken anywhere probably except for Minnesota, it’s a Turkey.

Bob St. Pierre: I would have sided with Chris, but I immediately thought of the ruffed grouse because of the drumming and the flush that sounds like a chainsaw, but when you bring up turkeys, you can certainly see the connection there.

Chris Niskanen: Let me take a stab at your question Hank, about why the ring-neck pheasant, and you might want to… This is purely speculation, no basis of fact here, but if you think about other animals that were introduced to the United States like the common carp, the Brown trout, these were fish and other animals that were really popular in their native countries and the idea that, well, if they’re popular over there, certainly they could be popular in the United States.

My guess is that back in the late 1800s, there probably wasn’t a lot of science that went into something like this. It might’ve been as simple as, well, what are the things that we could capture and keep them alive long enough to get the United States and what’s popular over there and what would be popular here? That’s just my speculation.

Hank Shaw: It makes some sense. I mean, it really makes some sense because… You know, survivability is a big deal because as we know our grouse species tend to be super nervous birds, and this is why you don’t have pen raised grouse really because they don’t withstand it where the pheasant does. So the other thing that people should know is that, well, why? Why did they bring these pheasants in? So they brought the pheasants in because market hunters had put the wood to prairie chicken so bad that the whole region, the whole upper Midwest, central Midwest was seeing a drastic decline in game birds period and unlike the sharp-tailed grouse, which doesn’t really like to hang around farms. He likes actual real grasslands of prairie’s. The prairie chicken didn’t really mind being super close to farms and so when they killed so many prairie chickens that their numbers had declined, they’re like, well, we’ve got to fix this.

We’ve got to put something different, and it’s the pheasant that’s stuck and one of the things that’s interesting about pheasants is their proximity to agriculture and there are very few upland game birds that I cover in this season. In fact, there are very few upland game birds period that really like farms. You know, most of them stay as far away from it as possible. Like the bobwhite hangs out around farms and cottontails hang out around farms and jackrabbits hanging out around farms, but the pheasant is almost always tied to agriculture and I can think of a couple of places where it’s not right on farms or on their marginal land, but that’s the exception that proves the rule.

Bob St. Pierre: I think that’s a 100 percent right and the other thing to think about is for the purists out there, the sharp-tail and the prairie chicken purists, and I love both of those birds as well, but if you don’t have pheasants and you don’t have Pheasants Forever fighting for CRP, fighting for WMAs grassland habitat, prairie chickens, and sharp tails go away a hell of a lot quicker without pheasants in their corner, because there’s just not enough people that loves sharpies and chickens.

There’s two million people that love pheasants and raise the voice to US senators, US representatives, the US department of agriculture and if you do license counts of how many people hunt prairie-grouse, you’re talking in the… It’s a few thousand. You maybe get into 20,000 people across the country that buy licenses to hunt prairie-grouse. There’s two million people in a good year that are going to buy [inaudible 00:33:56], to hunt Pheasants, and they carry the weight to protect the prairie that benefits sharpies and chickens as well.

Hank Shaw: So here’s a question for the people who don’t live in pheasant country, which is to say the center of the country. Everybody listening to this who hunts these birds has a story about, well, there used to be eight trillion pheasants in insert place here and there are not that many pheasants here or any pheasants here. So I’m thinking primarily of the old Midwest, like Pennsylvania and Ohio and New York and New Jersey and I’m also thinking though about the West as well.

I mean, I can tell you and I’ll start this conversation by saying, I know exactly why there aren’t any in California and as late as 20 years ago, there was buckets of pheasants here in the central Valley where I live because it’s agriculture and there’s lots of habitat for them and that’s the key with us, is that California is very, very efficient agricultural state and they pioneered the row-to-row kind of farming where your nearest row in whatever your crop is, whether it’s an orchard or a row crop is like three feet from the road and so there’s no more hedgerow and there’s no more… There’s nothing to put into CRP because everything is used because they’ve gotten so good at pulling everything out of the available land.

So there’s one County in the Valley that still hasn’t and that’s Yolo County, and they have consciously kept hedgerows and such, but it’s all private land and good luck getting on it and then there’s one public area that’s well-known for pheasants where I live and that’s the Klamath River Basin. So the Klamath Refuge and the Tule Lake Refuge up where Oregon and California meet that has buckets of pheasants and that’s just because you have a different kind of agriculture there. It’s more ranching and field crops rather than expensive stuff like fruit trees and row crops. So that’s why there, but there used to be pheasants or more pheasants in places like Ohio or New York or Pennsylvania. So what’s their problem there?

Bob St. Pierre: Well, when you talk about pheasant populations, and this is going to be true of any upland game bird you’re talking about, they’re two primary factors, habitat and weather, and that’s the simple… The simple answer is you need quality and quantity of habitat and you need favorable weather. For the most part, we can’t control the weather, right? The harsh winters, wet cool springs that limit reproduction, that’s a bit out of our control. Habitat is where it all comes back to and it’s… You know, you can talk about private land and public land, break it up into two slices, at the end of the day we’re losing habitat. Particularly if you dial us back to 2007. 2007, not that long ago, 13 years ago we had modern highs in bird numbers.

You know Minnesota harvested 600,000 roosters. Minnesota hunters did in 2007-ish, South Dakota two million, North Dakota a million, Iowa was a few years back, a million birds and that’s fallen off dramatically and the number one cause is a loss of habitat primarily driven in the 2010 timeframe by the advent of ethanol. Ethanol conversion of grassland CRP native prairie to corn fields for the purpose of creating ethanol really fueled the loss of habitat in a quick way and then precipitously wildlife populations particularly pheasants declined, water quality issues came in to being. We saw the commodity prices take a hit as well. So as you look out [inaudible 00:38:27], the next couple… In the last decade things are trying to balance out again. You know, the swing back to the CRP has gone from back in that 2007 timeframe about 36 million acres, it went as low as 20 million, and now is back up to 27 million and that is because very specifically land owners, farmers, ranchers want more CRP on the ground.

It got a little out of balance with that transition in the late 2000. So no matter where you’re talking in the country, Pennsylvania, New York, Iowa, the Dakotas or all the way out to California, the answer’s got to come back to habitat. The very specific reasons within the habitat is going to change a little bit. Some of it is loss of the fence rows. Some of it is there just not enough quantity, so it makes predators more efficient. You know, if all you have is roadside ditches and buffers, well, predators can hunt that linear cover really effectively.

You really need on a landscape to have quality bird numbers. You need a mosaic and a mosaic includes big blocks, it includes linear strips, buffers ditches connecting those big box together. It needs pollinator plots to add diversity in insects for Pheasants when they’re raising broods because when the summertime is happening, pheasants are not eating seeds, they’re a 100 percent eating insects. So you need pollinators to generate those grasshoppers and the beetles and the bugs, and it also relates back to what I talked about earlier where CRP isn’t a set aside program. We really have to actively manage that habitat so it is diverse, it’s not a monoculture of brome. Just one singular type of grass that’s only good for spring nesting and then it becomes virtually worthless.

So we really, truly need a mosaic on the landscape of all sorts of different things including agriculture and that’s where habitat and harmony with production agriculture is the sweet spot for Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever to work, to find the places they are saying is farm the best conserve the rest. So it’s… You know, we know that the country needs to produce food, fiber and fuel, but it’s got to be done in balance with water, quality soil and wildlife and rural economies that are propped up based on the Ag industry and based on the tourism industry that pheasant hunters and quail hunters bring into to places like Aberdeen, South Dakota, or Albany, Texas, or Albany Georgia.

Chris Niskanen: Can I just jump in there and add a little bit having [crosstalk 00:14:34], a lot? Bob’s absolutely right. I’ll take it up just a little bit higher level here for your listeners Hank, and it’s really about the change in agriculture and the industrialization of agriculture and you touched on it earlier, Hank. You know, how California had really invented this sort of row-to-row agriculture. You look back at all the old pictures of pheasant hunters in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s and farmers in Minnesota we’re living on small farms and they had what would be very primitive equipment for what we would look at right now. A farmer could make a living on 400 acres and wasn’t able to farm with the kind of efficiency that they started to see in the ’80s.

Even in my lifetime and even in my last 20 years, I’ve seen such an efficiency in farming. Even 20, 30 years ago you’d go to the most efficient farm and there’d still be that corner that had fence rows and that little piece that had foxtail and stuff, that’s all gone now and farmers are looking for the incentives to farm more efficiently and so really, what Bob was talking about is habitat has to sort of plug into the industrialization of agriculture in America and the efficiencies that our farm economy is always looking for that it’s not friendly to wildlife, and Bob’s also absolutely right. Conservation and agriculture need to work hand in hand and these sorts of ups and downs of pheasant populations are really tied to the farm economy. Last thing I’ll say is that pheasants are really dependent upon private land conservation.

You know we cannot buy enough public land to keep a pheasant population at a level that sportsmen and women would be satisfied with. Minnesota has probably bought more public land than any other state in the country at least in the pheasant range and as one of the reasons I would argue that Minnesota is emerging as a really strong pheasant state because we’ve made those investments, but it’s still not enough. I mean, the amount of public lands in pheasant country, Minnesota, ranges between two and maybe six percent in a good County of land base in those counties. So I just wanted to throw that in there to kind of give that bigger perspective. Bob and I, and Hank, we all love farmers, but they’re driven by the market to be as efficient as possible and they got to make a living. So that’s kind of the big picture view of that.

Hank Shaw: All right, let’s kill some pheasants. So-

Chris Niskanen: Sorry about the little detour, but I wanted to throw the farmer back in the discussion here because she, and he are really important here.

Hank Shaw: Absolutely. Absolutely. So mechanically, this is a… It’s a different style of hunting for the most part than any other upland bird hunting. Maybe some people will bobwhite quail hunt this way, but the signature pheasant hunt… And obviously there’s many different ways to hunt them, but the signature pheasant hunt is virtually military. It’s sort of a football like where you’ve got big lines of people walking across fields and everyone’s talking and there’s dogs coursing in front of you and the pheasant hunt in that is in most people’s minds eye is a group thing especially in the early season.

So there’s a communal aspect to it that is… The only thing that I can think of that is equivalent to that is dove hunting, where in the South, you’ll get 50 guys in the field shooting doves and I have been part of 25, 30 man lines for pheasant hunting and again, this is that pageantry of that opening week of pheasant hunting, where the whole world comes out to Southern Nebraska or South Dakota or Kansas, and it’s like a big party and it’s one of the things that sets pheasant hunting apart from say ruffed grouse hunting, where you’d never have 15 guys in the woods chasing ruffed grouse, all connected to each other in some way.

I mean, apparently they do have big giant grouse hunting but that seems weird, whereas it does not seem weird for pheasants. Now, once the season goes further than a couple of weeks then it starts to break into… Looks more like what you and I have done Chris and Bob, which is to say like there’s three of us, or there’s four of us and I actually like that big group hunt in the beginning of the season for the same reason everybody else does. It’s all folks’ homes. Like everybody’s back, you see your friends. You know the birds are less important because they’re going to get shot, somebody is going to shoot one, it is fine. It’s less about putting three birds in your bag than it is to see people you haven’t seen all year and then you put your serious bird weight in your bag for the next month and a half. Am I right?

Chris Niskanen: I’d say yes. I’d like to ask Bob if he thinks pheasant hunting is moving away from those big lines of people. I’ve done that before, I absolutely loathe it. My idea of a great opening day is maybe four to six people pheasant hunting in a line with dogs coursing in front of you. I’ve done the big stuff, where you got long lines of people in South Dakota, and it’s just awful. I hate it. Other people are shooting your birds for you. You never know who shot what bird, and it’s just… It’s dangerous and I kind of have a bad attitude about it.

Bob St. Pierre: Well, I think Hank is right that, that is the opening day sort of tradition particularly and you mentioned it Chris, South Dakota. You know the visual pageantry that you see in photography and in outdoor television shows in South Dakota is clearly the pheasant capital of the country. I mean, they harvest the most birds by far and the opening day group march that Hank refers to is the signature sort of way to do it, but I’ll agree with Nisky, I loathe that style of hunting as well. You know it’s fun for the comradery, but it completely takes most of the dog work out of the mix, particularly if you’re… I guess, here comes the point, the sensibilities in me. You know if you’re running pointers and flushers together with a march of people, the pointer is just at a disadvantage completely and it takes a lot of the enjoyment.

Given all the options of pheasant hunting, I am a solo a Hunter, just me and my dog, but I certainly do it in small groups. But I think that does make part of the beauty of pheasant hunting in that you can do it in a variety of ways and be successful and we’re going to see that this year, the year of the pandemic because I think you’re right, there’s going to be a lot of marches out there this year because the license sales are through the roof no matter what state you’re talking about. So there’s going to be a lot of group gatherings and the solo hunters are going to probably be hunting later than normal this year.

Hank Shaw: You kind of both alluded to it in a bit, but before we talk about dogs because there is an important part of this. What are your tips on dogless hunting pheasants? Because I am a dogless hunter and I’ve killed any number of pheasants and I have some tips, but I want to hear your guys’ advice because you have hunted collectively pheasants way, way more than I have. So if you don’t have a dog and you’re trying to kill some pheasants, what do you do?

Chris Niskanen: It’s actually a great way to learn how to pheasant hunt. I think what you’re going to do is you’re going to learn how pheasants behave and where they hang out, which is going to be different at different times of the day, but you really want to… And again, I think it depends on the time of the day, but early morning, you’re to want to be along those field hedges where there’s food and the thickest cover possible I would probably focus on, and then in the evening is the same thing, in the afternoons they’re going to be in the corn or they’re going to be in other places. I don’t know Bob, what do you think?

Bob St. Pierre: Yeah, I think your prime times are morning, whenever you’re shooting hours begin and your golden hour, the end of the day and walk in the edge of crops and generally you can catch birds moving out of their feeding time into their roosting areas. If you’re hunting midday, think like a coyote, hunt linear cover, hunt ditches, hunt buffers. A pheasants survival instinct is not to fly, a pheasant survival instinct is to run around you. So with the dog component is getting the pheasant in the air, pinning a pheasant to a location til they have to flush. If you don’t have a dog, you need to get that pheasant into the air.

So you’re hunting linear cover, you might be hunting in circular routes and thick cover like Chris talked about, but your goal is to figure out how to get that bird into the air that’s… And then I would just say, be an excellent shot if you’re going to hunt without a dog. Pheasants are tough SOBs, you got to whack them really hard to drop them dead if you don’t have a dog to help you recover them. So don’t take those 50 yard shots and just wing a bird because pheasants are survivors and without a dog and without a good shot, you’re just going to cripple a lot of birds.

Hank Shaw: That’s some good advice, especially about the shooting aspect of it. You might also if you’re dogless, bring gnarlier shot like Bismuth or like… Prairie storm is actually quite good, but bring like fives or even fours and it has put that bird down. My other piece of advice for dogless hunters is to hunt small cover. So if you’re in the pivot zone, hunt those weird triangular hedges of the pivot, because typically the triangular hedges that are not in the circle are overgrown and they have birds in them and a single person can work through those little spots and if there’s a bird there it’ll get up because it doesn’t have anywhere else to go because typically on the circle part there’s nothing there and then there’s often a road or a dirt road or a path on the other sides of it.

Little sinks, so if you’ve got a big old giant field of something and you know those little sinks that you’ll see in those fields, there often be cattails in those and sometimes even actual water in the center of them, but they’re isolated, right? Because the farmer has farmed around it and those little weird patches that are otherwise in agriculture, those I have found would have held dozens quite a bit and you see that a lot in Klamath up in Northern California where I hunt.

Bob St. Pierre: The pivot is a wonderful example of where to hunt without a dog. And it’s also a terrific example, those corners for wildlife, where the farmer and the hunter intersect, and they both get a benefit. Conservationists, a farmer gets paid on those corners for wildlife program and the hunters get some extra habitat for those birds. Those are places you got to be ready, not only for pheasants, but there are terrific places to find bobwhite quail in states like Nebraska, Colorado, and Kansas. So those pivot corners are terrific examples for places to hunt without a dog.

Chris Niskanen: Hank, can I talk a little bit about footwork?

Hank: Yes.

Chris Niskanen: And this is something that I think a lot of beginning bird hunters don’t think too much about. It’s something I’ve talked to a lot of new hunters about. You’re hunting pheasants and you’re walking across uneven terrain and you’re carrying a six to eight pound gun, and your natural tendency is going to be looking down at the ground to make sure you don’t fall on your ass because you do it a lot. And what you need to do is train yourself to be looking up all the time and anticipate the terrain in front of you and be able to walk in a way that you can always have a stable shooting platform from. So you see the pheasant flesh and then you stand and you shoot.

Talking about the dogless hunter, you want to take that shot as soon as possible. When that bird flushes, you got to identify it as a rooster, you got to estimate its distance and you got to make a good clean shot as it’s either flying away from you or maybe banking. And there’s nothing more important than having a good stance and not falling over, having your feet tangled up in some brush or whatever.

And I just think beginning hunters and even experienced hunters, just pay close attention to where your feet are all the time. And if you do this enough, you will start to be able to walk without ever looking down at all, your feet just know where to go. I think it’s just true of also hunting and thick cover in the woods. I’ve seen a lot of beginning hunters walk through the woods and they’re falling over all the time. And frankly, if you’re a beginning pheasant hunter and you’re not falling over a little bit, you are probably looking at your feet too much. So, I don’t know, Bob, what do you think?

Bob St. Pierre: It definitely resonates with me when I think I just got done ruffed grouse hunting and the seasoned vets are thinking about their foot work, carrying the gun, port arms, looking for shooting lanes. It’s pretty intuitive when it comes to ruffed grouse, but it’s often overlooked from a pheasant hunters perspective and you’re walking those uneven WPAs and WMAs, and you’re walking through willow thickets, that’s the cover that pheasants are going to key in on certain times of the year. So just like a center out of basketball team, footwork’s awfully important for the pheasant hunter.

Chris Niskanen: Yeah, no kidding. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve been ready to shoot a rooster and I step in a badger hole, or I’m trying to untangle myself from some really thick weeds, or I have a cattail in my eyeball.

Hank: Can I just stop you for a second and say, go Badgers?

Chris Niskanen: Go Badgers.

Hank: I know you guys are both Minnesotans and I went Wisconsin. [crosstalk 00:57:48]

Chris Niskanen: -a house, so I’ll send you a picture of my stuffed Badger, Hank.

Hank: I know, it’s the closest Minnesota is ever going to get to beating the Badgers.

Chris Niskanen: Ooh.

Hank: I can see the chagrin on both of your faces right now, it’s pretty epic.

Chris Niskanen: Well, we have a Gopher, and we have a Badger, and we have a Wolverine on this call. So we could seriously have a discussion about.

Hank: It’s true. I think we have to give the nod to the Wolverine as the nastiest of the three animals.

Bob St. Pierre: That’s true, fitting for my personality.

Hank: All right. Dogs. So this is a good one because Niskie runs flushers and you run pointers, Bob, fight, fight, fight.

Chris Niskanen: I’m envious of Bob, because in my darkest part of my heart, I’d love to have a really good pointer right now.

Bob St. Pierre: Well, you’re not going to get the fight you want Hank. But if I lived in Minnesota, Iowa, and exclusively hunted pheasants, I’d own a Labrador, where pointers for me or the right fit is the traveling diversity of birds that I hunt. If I’m going to run big in Montana, the grouse woods, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where I’m from, quail across Nebraska, Kansas, and pheasants in all those states, that’s where I gravitate towards the pointer, because the Canada Swiss Army knife of the Upland world, if you wanted to just pound those cattails and get roosters in Minnesota or South Dakota, then you should own a Labrador.

Hank: Really, that’s a lot less of a fight than I expect, I’m disappointed.

Chris Niskanen: I’ve hunted with some really fantastic pheasant hunters. I’ll drop a name right now, Gary Clancy, he has a wildlife management area named after him. He was a Brittany guy to the very end, and he had such an incredible relationship with his Brittanys and to watch them hunt together, and Gary always hunted with a 20-gauge, sometimes with a 410. He was really an iconoclast and he was a healthy shot. If you weren’t on your toes, that rooster was going to be in Gary’s bird bag before you knew it. So, did you ever hunt with Gary, Hank?

Bob St. Pierre: No, I haven’t, but his stories are lore. He was ex-Vietnam I believe, and he would hunt through the toughest weather and he survived, he hunted with cancer for many, many, many years during radiation and chemo. And he just loved pheasant hunting so much that he’d knock them on his ass at the end of the day with all the chemo and the radiation, but it was also what kept him going. And that’s testament to how passionate you can become with a connection of the bird and the connection with the dogs that you mentioned with the Brittanys that he loved.

Chris Niskanen: I’ve hunted with [inaudible 01:01:15] and GSPs, and all different types of pointers, Munsterlanders, Brittanys, and all different types of flushing dogs, Springers. Some of the best hunting dogs I’ve ever seen, we’re none of those, they were a mix of them. I have a friend, Chris Winchester who always gets his Labrador retrievers from the pound and these dogs might not look like your classic Labrador retriever, but he has such a close relationship with his dog and he trains them so well that he just has amazing hunting dogs. I’ve learned so much from people like this about pheasant hunting who’ve just applied just real practical things. Mitch Keizer, I think hunts with Terriers, doesn’t he?

Bob St. Pierre: Yeah, he does. He has a couple of Terriers that flush the bird and they’re so small that they can’t retrieve it. So they stand on top of it.

Hank: Well, that’s like Smidge, Anthony Hauck’s dog. He’s like a micro Cocker or something.

Bob St. Pierre: Yeah. He’s got Cockers and Cockers are wonderful dogs. And there’s, Airedale Terriers, there’s a group that not a group, but a contingent of people that just love Airedale Terriers for hunting and Poodles, even Poodles have a long history of being hunting dogs. I know you wanted a little bit of a fist and cuffs here over birth dogs. And I’m a passionate lover of short hairs. I grew up with Brittanys. I grew up with Brittanys, my wife grew up with Labs. She wanted a bigger dog, I wanted a pointing dog and the merit of compromise was a short hair.

But there’s so many choices and they’re all wonderful. It becomes a very individual preference based on what you like to look at, because you’re going to have that dog 365 days a year, the style of hunting you like, and the type of birds you like and where you live and where you travel. It’s a pretty complex question. And also throw in, do you live in a house with acreage, or do you live in an apartment? And there’s so many variables and then it becomes a really, really personal choice. And it’s hard to pick a fight with anybody over their dog choice because the longer you’re in this, you see wonderful individuals out of every breed.

Chris Niskanen: Hmm, I’ve had it with some beautiful Vizslas, I’ve hunted with some goofy Golden Retrievers that totally got it done in this field. I think more importantly is not the breed, but the training of the dog. And I will say I believe in having good bloodlines, but if you have a dog that has an inclination to hunt birds, give it a shot, why not?

Hank: What about other gear? You guys both are familiar with Tinkerbell, the 20-gauge over and under that I’ve shot almost exclusively for almost 20 years now. I have switched to an A-400 for ducks, but the 20-gauge over and under, I swear by it. And I’m going to shoot led fives or sixes at pheasants or bismuth sixes. If I shoot straight up still, I think I’m going to go with just fives. Fives are always good and definitely high base and definitely three inch and 20-gauge. I’m not going to shoot a two and a three quarter inch shell out of a 20-gauge, but I would for a 12. And, hey, I want to actually just a side note, I forgot to say, when you’re talking about dogless hunters, and this is a thing that I don’t know, Niskie you might’ve taught me this, but I’ve used it, and this works.

You get a radio like a transistor radio or some portable radio, and you turn it on at the other end of whatever the cover is that you’re going to go for. And I like to turn it to Rush Limbaugh because bird’s hate Rush Limbaugh. And I think it’s his tone of voice or whatever, but talk radio is what you want. And you put that in, you turn it on and you sneak over the other side of the field and then you walk towards your radio. And then that radio becomes a blocker so that the chickens don’t run away from you, and it never takes it the air because once they’re running, running, running, and all of a sudden they hear Rush Limbaugh, and they’re like, “Oh my God, I hate Rush Limbaugh.” And they fly, and then you get the chance to shoot. I don’t know if-

Chris Niskanen: You didn’t get that from me Hank. But it is pretty original, I’d have to say.

Hank: It works.

Bob St. Pierre: This segment of pheasant hunting tips brought to you by Spotify. Well, I do want to mention in that to make this into a commercial, but you bring up Prairie Storm, I shoot Federal Prairie Storm Steel. I’ve gone pretty much non-toxic for all of my bird hunting. And, I think it is important for bird hunters to know that there are companies that support the habitat mission of the organization. And Federal is one of those that has contributed, and they see the long game to conservation. And that’s critically important in the midst of this COVID situation, where organizations like ours have lost all these banquets and membership is a challenge and companies. We really need the companies that stick with us and make a contribution.

And Federal is one of those that’s been with us since the mid ’80s. And I bring that up and tie it back to you, Hank, because your book; Pheasant, Quail, Cottontail is another example of… You’re not a corporation, but you’re a person that believes in habitat, wild birds in our organization’s mission. Not only are you a life member of Quail Forever and a member of Pheasants Forever, but every time somebody buys Pheasant, Quail, Cottontail, no matter where, whether it’s through our website, your website, Amazon, you give a contribution, a completely unattached contribution to our organization to fulfill our habitat mission.

And I want to bring that up at and publicly thank you on your own podcast for making that commitment, but also to reinforce the importance of… There’s an awful lot of companies that make a buck on wild bird hunting in public lands, but there’s an awful important group within that corporate world that also give back beyond just PR dollars, Pittman, Robertson dollars beyond that, they make contributions to Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever and Ducks Unlimited, and the Ruffed Grouse Society, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers. And that is so critically important. So first of all, thanks, Federal, and second, thank you, Hank Shaw. How about you, Chris?

Chris Niskanen: I would say that five is the best overall shot, and I want to just throw a big kudos to Bob for promoting pheasant hunting and the people who helped pheasant hunting. Because without that, pheasant hunting wouldn’t be here today. People needed to speak up for the birds, whether it’s in Congress or it’s at your local pheasants forever chapter or whatever fives I think are the overall best. If you’re shooting steel, I think most people are going to be shooting twos and fours. So Bob mentioned, non-toxic Bob, what size shot-

Bob St. Pierre: I do shoot the steel fives. But you got to remember I’m shooting over a pointer. And I generally shoot Prairie Storm Steel, which packs a wallop and a shoot skeet chokes to open up that pattern over a point. So I think it’s important for bird hunters. Too many folks just throw in the improved cylinder choke and go with fives and head out into the field and call it good. And it’s pretty important to pattern your gun. Think about the time of the season and the style of dog you’re hunting over, but yeah, fives, steel, ski choke.

Chris Niskanen: And to you, I would agree with that. I’ve not patterned my gun. The inevitable Vikings coach, Bud Grant used to say, “I don’t ever practice my shotgun because I want to be surprised when the bird gets up.” Famous quote from Bud Grant. I’m often surprised by the fact that I hit most of the birds. I have a friend, Bill Marshall, who says, “You should never miss a pheasant.” And by that he means, don’t shoot at a pheasant that you can’t hit. And also if you’re pairing the right shot with the right gun, and you’ve practiced with that gun, you shouldn’t miss. And I’ve thought about that a lot, and he’s right, you should hit 80% of the birds that you’re shooting at or more. As to the type of gun to use, Gary Clancy shot with a pump 20-gauge, I think was given to him by his grandpa.

He was lethal with that gun because he had shot at his whole life. And he knew how it worked. I wouldn’t say I’m as lethal as Gary Clancy with my old Benelli, but I really know how it works. And one of the biggest excuses maybe that I hear from pheasant hunters, I couldn’t get my safety often time. And I think that experience you know where your safety is and you know how to get it off, but being really super familiar with your firearm, how it works, how it feels in your hands, how to get the safety off in a split second will make you a really successful pheasant hunter. And it’s that kind of familiarity with your gun is always going to triumph, having a pretty. Hank, do you have a favorite gun that you’ve shot your whole life?

Bob St. Pierre: Yeah. I started like most kids with a pump. Mine was in Ithaca. I’ve grown to really become fond of rounders I love being able to crack the over-under open over my shoulder and grab the bird out of the dog’s mouth and not have to worry about setting the gun down and having a misfire. But yeah, you can’t really go wrong with most of the big brands. Find something that’s relatively light and you can carry comfortably for 10 miles and you’ll be in good shape.

Hank: Yeah. I think weight of the gun is important and I would strongly advise all new pheasant hunters to use a 12-gauge and then scale down as you get better.

Chris Niskanen: Yep. I would agree with that. And I think Bob’s right. Guns are designed now to be light. If you are going to carry your dad’s gun, that’s super heavy or grandpa’s gun, really do some research on that gun and make sure it fits you well, take it into a custom gunsmithing shop and have them make the stock that you, whatever wedging you might need for that. But also with any new gun, make sure it really fits you. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve hunted with my father-in-law and he had a gun that didn’t fit him. It was a beautiful gun, expensive gun, but it didn’t fit him well. And he would miss five, six birds in a row and it drove him bananas. And I finally said, “Take it into your gunsmith and get it fixed.” And when he did that, it was an epiphany for him.

Hank: Oh yeah. I mean, it’s one of the first things I ever did was get my Franchi fitted to me. And it changed things dramatically because you’re, right-handed, Chris, and all the guns I borrowed from you. I couldn’t shoot worth a damn because I’m left-handed cause they’re all canted the right way for me.

Chris Niskanen: Exactly. I don’t know how you ever did it.

Hank It takes a little bit longer. You lift the gun and then you torque your wrist a little bit. So, it makes me about a second and a half slower than with a gun that’s fitted to me.

Chris Niskanen: Yeah. And also the whole dominant eye thing and you did right-handed, really important things to consider when you’re a beginning bird Hunter.

Hank: So if I’m going to send a guy from the coast or from the South or wherever to pheasant Nirvana, I’m going to send him probably to either Nebraska or Kansas. I’m actually not going to send them to the Dakotas because I have found that there is a calmer hunting, as many, if not more birds, it could be like cloudy with a chance of bobwhite quail, which is always nice. And then if you go to Western Kansas, you also have prairie chickens that you can hunt. And I forget, I think it’s either Kansas or that actually gives you four birds, which is the only state in the union that does that. I know you guys are probably more partial to the Dakotas, or maybe even Minnesota as a destination. But if somebody was going to do a destination pheasant hunt, where do you send them?

Chris Niskanen: I think I would agree with you, Hank. If you’re sending someone from California, Oregon, Kansas, Nebraska are good choices. I know a group of guys in Oregon who drive to central North Dakota every year and spend a month there, an odd place to end up if you’re from Oregon, because you drive past some really good pheasant hunting. There’s fabulous pheasant hunting in Montana. If you’re in Washington, there’s some great pheasant hunting along the Columbia river there. It’s not just the Midwest anymore. Bob, I don’t know. I hear great reports from some of the Western States in Colorado. There are birds in Colorado?

Bob St. Pierre: Yep, they’re found in Colorado. Well, so to answer your question, Hank, if you’re purely going for a pheasant hunt, then I’m sending them to South Dakota. I mean, there’s no doubt about it. I’m sending them to Chamberlain, Mitchell area, maybe Pierre, if you’re just going to hunt pheasants. Now it gets to be more complex because you throw in cloudy with a chance of Bob Boyds. And if you want a forest and prairie, if you want ducks and then, or beautiful scenery, like if I want the most pitcher S pheasant hunting on the planet, I’m going to Montana, probably going to Lewistown, Montana and get a hunt in the shadow of the Rockies. If I want the best mixed bag, you know, chickens, sharpies, quail, and pheasants, I’m probably going to Nebraska. If I want another mixed bag and I can shoot four roosters, a quail, and prairie chickens then I’m going to Kansas.

If I want to do a morning duck hunt in an afternoon pheasant hunt, I’m going to North Dakota. If I want to do Prairie and forest combo, and try to shoot the ultimate mixed bag in my opinion, which is pheasants and ruffed grouse. I’m going to Minnesota. I was on the list for quail and pheasants too. But if you purely put the proverbial gun to my head to go on a pheasant hunt and I’m going to just purely chase roosters. It’s the pheasant capital of the country, 2 million roosters a year that’s the South Dakota.

Chris Niskanen: Can a guy or girl show up in North Dakota without a guide and find a place to hunt in South Dakota?

Bob St. Pierre: South Dakota, a hundred percent? Oh yeah. There’s actually a ton of public land in South Dakota because South Dakota has walk-in program. And that put you towards the James River crap. So follow the James River on the map from Aberdeen down and they have a walk-in program built on private land to create public access. So they got that, they got waterfall production areas, they got game production areas, which are state-owned lands. They have, like you mentioned the Sand Lake Wildlife Refuge, wildlife refuges for Upland birds are probably among the most overlooked places to go bird hunting. There’s some in Northern Kansas that you can get into this remarkable pheasant and quail hunts. So public lands, the Dakotas are terrific. As you mentioned earlier, Minnesota has permanent public lands, WMAs and WPAs in the pheasant range that are the gem of Minnesota. Minnesota is for sure the most underrated pheasant destination in the country.

It has the highest population of people in the pheasant range. So there’s a little bit more pressure, but it has more birds than people give credit for. So I think this is a weird statistic, but I believe Kansas and Iowa are two of the bottom three States in terms of public lands. So, 48th and 49th in terms of total number of public lands, which is really bizarre when you consider Connecticut, and Delaware, and Rhode Island. But thankfully they’re making some inroads there. Kansas has a million plus acres of WIHA, a walk-in program, and Iowa has IHAP, which is Iowa habitat access program, which is another access program built on top of private land.

And some of these walk-in programs, I think about Iowa’s IHAP, and Nebraska’s open fields and waters, incredible properties. They’re private lands. The state governments are paying those landowners to improve the habitat on the property and they open it up to public access. Again, it’s another intersection with the landowner, the farmer, and the Hunter, and I’ll call up those two in particular, Nebraska and Iowa, their access programs are off the charts when it comes to terrific hunting opportunities and wildlife species. I’ve hunted on both extensively and you can get into just terrific pheasant, quail and Prairie grouse numbers.

Hank: Hmm. Well, before we stop, because we’ve been a long time, we can’t leave without talking about eating pheasants. So this is my area of expertise, but obviously I want to hear from you guys as well. And I always start the food talk with the issue of, hashtag give a pluck. So few pheasant hunters actually pluck their birds. And I think that’s a serious shame.

The advice I give for pheasants is the advice I give for any of the grouse species, which is to let the bird chill out in the refrigerator for several days before you attempt to pluck it. If you try to pluck a pheasant, when everybody wants to pluck a pheasant, which is that afternoon, or the next morning, the feathers will still be so strongly attached to the bird that you’re going to tear the skin virtually every single time. They age really, really well. Most of the meat science done on the aging of birds has been done on pheasants because you can buy wild pheasants in England and in Australia. So there’s a bunch of science on it, and I’ll put a link to hanging pheasants in the show notes. The general takeaway has been that most people who eat aged pheasants prefer them aged for five days, at 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

And that is a perfect window for a wild rooster. You’re going to hear, “Oh, well, other group of people here hang them until their heads fall off.” And it’s actually a myth. It’s a rural myth, it’s not an urban myth. It’s because nobody does that. Nobody does that. They always talk about somebody else doing that. And what really people do is, I’ve seen them as aged, as long as 10, I heard 14, but you’re starting to get into some gnarly area there. Bacteriologically, if your temperature never goes above 55, you’re always in good shape. But the short version is, get your birds as cool as possible from the second that they hit the ground. If you’re hunting pheasants on a hot day, which happens, consider clipping a duck-style game strap to that little loop that’s in the back of your game vest.

Because every game best has a pouch in it, but it’s got a little loop on the outside as well. And consider attaching a duck-style game strap to that loop, so that you can hang your pheasants from the neck while you’re still hunting, and they’re not stuck in your pouch, which is very, very hot and closed place. It can actually damage the birds significantly, if you’re hunting in 75 or 85 degree weather. And then when you get home to the truck, don’t stack them up, line them up so that they can continue to cool that way. And if you don’t have a cooler, if it’s over 60 degrees when you’re hunting out, you need a cooler for your drive home, or for your drive to the hotel. And then, just keep them cold from then on end for at least three days, and then pluck them. And they are going to be perfectly fine.

And no, I’m not gutting. Everybody’s like, “Well, your gut the first, right?” And like, “Nope, you don’t got them [inaudible 00:02:57].” The only animals that you need to gut before aging are bigger than pheasants. So turkeys are one, geese, especially. And then you can just kind of go from there. You’ve heard it from the horse’s mouth. I mean, I’ve done this a billion times, and it works really, really well for me. What’s also good is a lot of people like us, like we’ve been talking about at the beginning of this podcast, will travel. So they’re like, “Well, what do I’m doing? I’m staring at a hotel!” Keep them cold. I have stocked untold numbers of upland game birds, holding onto the feathers, in hotel refrigerators. And the only thing you need to do is just, don’t be a jerk, and pick all the stray feathers, and clean up any blood that’s in there before you leave the hotel because it’s kind of a dick move if you don’t do that.

But I have kept birds on a 10-day road trip, perfectly fine. And you end up plucking them four, five, six days after you hunt them. By the way, I’m a plucking Jedi. So I can do this in a hotel room and leave no feathers. It’s a skill. But if you don’t have that kind of skill, find a place where you can pick into a garbage bag, if you’re on a longer trip. But most people are just like, “You just do it when you get home.” Or if you’re in South Dakota, like you were saying before, it is such a pheasant-friendly place. There’re cleaning stations all over the place.

Chris Niskanen: Yeah. Well, Hank, you are to bird plucking, what Gary Kasparoff is to chess. You are a grand master, and I’ve watched you pluck. You have inspired me, and I’m sure you have inspired thousands of other bird hunters to stop pulling the breast out, and pluck that bird. I have a whole bunch of woodcock in my freezer right now that I would not have ever plucked if it weren’t for you so … Now I’m thanking you. I’m sure there are lots of spouses all over North America who probably hate you because now they’ve got pheasants hanging in there, bleeding all over their car, hanging from the garage for five days and … What spouse does it love that?

Hank Shaw: Oh, my favorite is while you’re putting them in the refrigerator, you can put them heads out at your children’s eye-level.

Chris Niskanen: Perfect. Next to the pizza that you’ve also put in there. That’s-

Hank Shaw: Exactly.

Bob St. Pierre: I’ll definitely agree that plucking is the way to go if you are a Jedi master like Hank. Fundamentally, I’ll just implore people, because I see it every year where, they’re just saving the breasts, and throwing the rest away. If we could get pheasant hunters to take one step, and that’s to save the legs.

Hank Shaw: Yes.

Bob St. Pierre: Ultimately it’s illegal, because that’s wanton waste, but you’re throwing away an absolute gem. If you don’t have the time to pluck, and I get it because, I’m not a Jedi master. Honestly, I pluck one or two birds a year, but I never ever throw the legs away. The legs are just terrific in tacos, and soup, and pulled pheasant sandwich. I mean, there’s so many things you can do with them, and they taste incredible, and it’s so easy. So the very minimum, save the legs.

Hank Shaw: 100%. To add to that, save the legs skinned or plucked, and take shears, and as you collect pheasants, separate the drumsticks from the thighs. So you have a packet of drumsticks and, a packet of thighs, because with the exception of the wild turkey, there is no bird that I’m aware of, that has nastier, tendons and sinews in its drumsticks than a pheasant. I mean, we’ve been talking this whole podcast about how a pheasant is likely going to run away from you, and not fly. They have big, strong, powerful legs. And by separating the thighs from the drumsticks, you have a whole packet of things with only one bone, which is the thigh, and then you have a whole bunch of things that you can then slow cook. You throw them in a crock pot, and then you pull the meat off the tendons.

Now, there is a trick that sometimes works. And I mean, it’s not a hundred percent, but you can partially sever the foot at the knee with a knife. You don’t want to do this with the sheers, because you’re typically going to go right through. So if you imagine all birds, their knees like a square, there’s four points on it, and there’s two points above the foot, and there’s two points below the foot. You know I’m talking about? Two are attached to the foot, and two are attached to the thigh. So you run your knife in the center of that square, and that will open up that knee, right at the joint, you won’t touch bone at all.

Now, you almost totally sever it. And now, you take the foot, and you twist it around, over and over and over and over and over again, maybe four or five revolutions, while holding the actual drum stick with your off hand. I’m pantomiming it right now and a since I’m left-handed, I’ve got the foot in my left hand, and it’s been twirling around, and I’m holding that drum stick tight with the right. So when you’ve got two or three revolutions, you hold onto the drum stick for dear life, and you yank, and that will pull virtually all of the tendons out of the drum stick.

Chris Niskanen: Amazing.

Hank Shaw: It’s doesn’t always work, because sometimes the Achilles of the bird just breaks. But when it works, then you have a drum stick that you can eat with virtually, no problem.

Chris Niskanen: Cool.

Hank Shaw: Yep. See?

Bob St. Pierre: Yeah, you got to do a video on that because-

Hank Shaw: I will.

Bob St. Pierre: There’s an old outdoors show guy that did a video on that, on the sidewalk, and it needs to be updated Hank Shaw style.

Chris Niskanen: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Hank Shaw: Giblets are another thing that I implore people to keep. The gizzards of a pheasant are large enough to work with. The hearts are very easy to get out. Livers, I will keep them if the livers are light colored. So the light colored liver is an indication of fat. So if you buy chicken livers in the store, you’ll notice they’re tan, and not burgundy. You will get pheasants that will have tan livers. And that means there’s fat in them, which means they’re going to taste way better than say, a sea duck liver, which is going to be as burgundy as you get and very strong flavored. I also collect them by giblet, packet of livers, a packet of gizzards and such, and as you collect them and, virtually all of these giblets tastes more or less the same, species to species to species.