As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

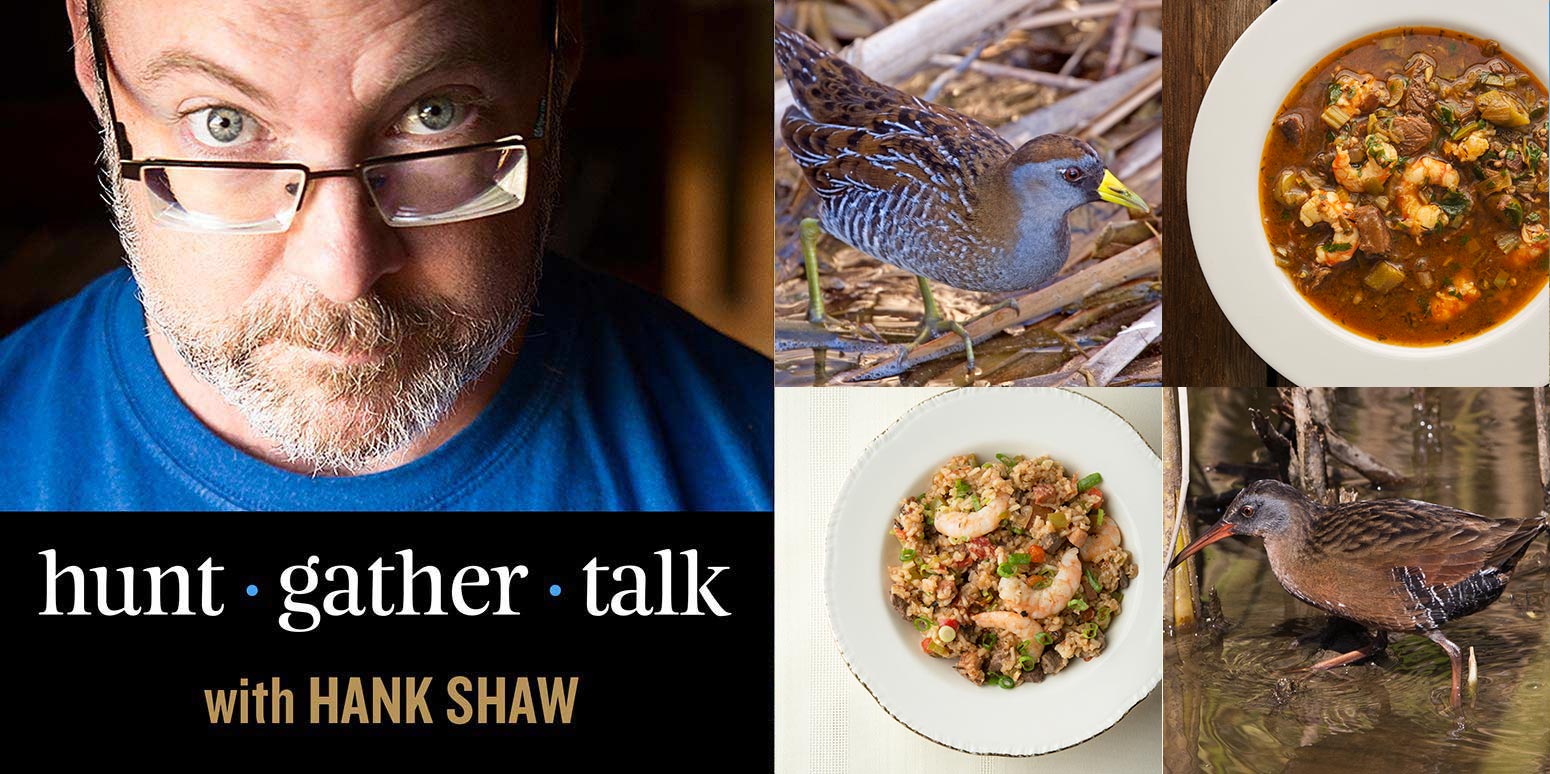

Welcome back the Hunt Gather Talk podcast, Season Two, sponsored by Hunt to Eat and Filson. This season will focus entirely on upland game — not only upland birds but also small game. Think of this as the podcast behind my latest cookbook, Pheasant, Quail, Cottontail, which covers all things upland.

Every episode will dig deep into the life, habits, hunting, lore, myth and of course prepping and cooking of a particular animal. Expect episodes on pheasants, rabbits, every species of quail, every species of grouse, wild turkeys, rails, woodcock, pigeons and doves, chukars and huns.

In this episode, I talk with University of Illinois biologist Auriel Fournier, who specializes in rails, as well as Dave DiBenedetto, editor of the magazine Garden & Gun, who is also a serious rail hunter in South Carolina.

This is an unusual episode in that I have never successfully hunted the true rails, although I have hunted their relatives, the coot and the moorhen. The four huntable rails — sora, king, clapper and Virginia rail — are the biggest gap in my gamebird experience.

For more information on these topics, here are some helpful links:

- Learn more about sora rails, and you can hear their cool “whinnie” on that page (bottom right). Here’s a short video of a sora eating things in a marsh. And here’s a cool research project tracking the migration of soras on the East Coast.

- Information about Virginia rails, plus the sounds that these rails make.

- A species account of clapper rails, plus their vocalizations.

- Finally, learn about the king rail, the largest huntable rail, and what it sounds like.

- My story about hunting pukekos in New Zealand. Pukekos are a rail, similar to our purple moorhen.

- Some good rail recipes: Lowcountry perloo, in honor of Dave DiBenedetto, and my take on the venerable popper, which works great with sora rails.

A Request

I am bringing back Hunt Gather Talk with the hopes that your generosity can help keep it going season after season. Think of this like public radio, only with hunting and fishing and wild food and stuff. No, this won’t be a “pay-to-play” podcast, so you don’t necessarily have to chip in. But I am asking you to consider it. Every little bit helps to pay for editing, servers, and, frankly to keep the lights on here. Thanks in advance for whatever you can contribute!

Subscribe

You can find an archive of all my episodes here, and you can subscribe to the podcast here via RSS.

Subscribe via iTunes and Stitcher here.

Transcript

As a service to those with hearing issues, or for anyone who would rather read our conversation than hear it, here is the transcript of the show. Enjoy!

Hank Shaw:

Hey, there. This is Hank Shaw with the Hunt Gather Talk podcast, sponsored by Filson and Hunt to Eat. I am so glad you have joined me for another episode, and this episode is special. It’s special for a couple of reasons, not only because it’s the first three-way podcast I have ever done, so we have two guests today, but it’s also special because this may very well be the only episode of the entire season where the subject is something that I have not directly hunted. Now, it’s not entirely true to say I have never directly hunted rail birds, which is what we’re going to be talking about today, but it is correct to say that I have never actually successfully hunted rail birds. I’ve tried it in Texas and I’ve tried it in a few other places, and I have hunted their cousins the coots, the moorhens, and the gallinules, including the wily pukeko all the way out in New Zealand.

But as far as the four huntable rails, the Sora, the Virginia, the Clapper, and the King Rail, it’s all a mystery to me, which is why I wanted to have two different people on the podcast today. Not only do we have Auriel Fournier, who is a rail expert and a biologist at the University of Illinois, but we also have Dave DiBenedetto, who some of you may know as the editor of Garden & Gun magazine, which is one of my favorite magazines. I always read it whenever I see it. Dave is also a really good rail hunter in the South Carolina Lowcountry, where rail hunting is actually a thing. So between the two, I figure we can get a really good grounding on these crazy birds.

Now, a lot of you, and myself included, are like, “Rails. I know you can hunt them. I see them in the regulations. But where are they and where do you go and how do you identify them and not shoot the wrong bird? And do they taste good, and are they worth my effort?” And all of this stuff is stuff that we’re going to go into at length in the next hour. I hope this episode lights a fire under everybody to try and seek out those crazy rails that are probably living in a marsh near you.

Welcome, welcome, welcome, Auriel and Dave. This is my first ever three-way podcast via Skype. And Auriel Fournier, you are calling me from the University of Illinois, right?

Auriel Fournier:

Correct.

Hank Shaw:

And Dave DiBenedetto, you are calling me from the great city of Charleston, South Carolina, right?

Dave DiBenedetto:

That is also correct.

Hank Shaw:

Awesome. So today’s topic is an unusual one for me because I think, in fact, it is the only episode of this season of the podcast where I have not actually hunted the animal that we’re about to talk about, which is one of the reasons why I wanted to get two of you onto the show today, because you guys have different areas of expertise. So Auriel, you’re a rail biologist, among other things. And Dave, you are a hunter and eater of rails, and you also live in an area where rail hunting is actually a thing, where in the rest of the country, rail hunting is almost as bad as snipe hunting, where it’s like, “Really? Do these birds actually exist?” And yes, they do.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Correct.

Hank Shaw:

So we’re going to take as much time as we need to demystify the mysterious rail birds. So let’s start with Auriel. Tell me a little bit about A, why rails? What’s your area of expertise? And we’ll take it from there.

Auriel Fournier:

Sure. So I got hooked on rails in high school. I was very outdoors-oriented and very interested in birds more generally, and got involved with an organization called Black Swamp Bird Observatory in Ohio, who at the time was running a rail project. So they were trapping rails to band them for scientific research during the spring migration. So I got to go out and help with that, and that’s where I really fell in love with wetlands and trying to understand wetland management and bird migration. Then I went on throughout my higher education and ended up doing my PhD studying the autumn migration of rails in Missouri and trying to better understand how we can manage public wetlands for water fowl and also provide habitat for migrating rails, focusing mostly on Sora, but also some on Virginia Rail and Yellow Rail.

Hank Shaw:

And was Yellow Rail one of the huntable rails in the United States?

Auriel Fournier:

It no longer is. It used to be, but not anymore.

Hank Shaw:

Got you. So Dave, how did you get started on the whole rail train?

Dave DiBenedetto:

It was a Boykin Spaniel. So I grew up in Savannah, Georgia, and I was a river rat, through and through. My family weren’t big hunters, much hunters at all, so I think I knew about rail hunting, but until I came back to the Lowcountry in 2008 to work at Garden & Gun, but when I did, I got a Boykin Spaniel. And at that point, I was looking for any way I could get out and hunt more with her. And the Boykin Spaniel’s tagline is, “The dog that doesn’t rock the boat,” which is kind of perfect for rail hunting because you want a small craft, so you’re either pushing it or rowing it, pushing with a pole. And it was the dog. I met a fellow Boykin owner who said, “Come join me.” And I went once and I fell in love immediately.

Hank Shaw:

Is it the law that every hunter in the South must own a Boykin?

Dave DiBenedetto:

Well, I can tell you that my Boykin is 11, and now I have a two-year-old Lab, so I’ll let you infer from that.

Hank Shaw:

I can tell you that I don’t know … I can’t count even on two hands the number of people I know who do not live in the South who run with Boykins.

Dave DiBenedetto:

There’s pride in place, and the Boykin is the Southern breed. I know this isn’t about Boykins, but that idea that you could have a pocket retriever, a 35-pound dog that could do essentially everything a Lab could do, except handle the real cold stuff. And I bought in big time. And thankfully, because of that, I’m a rail hunter.

Hank Shaw:

Well, we’re going to get into dogs a little bit later. Let’s start with habitat. You know what? Let’s not start with habitat. Let’s start with the birds themselves. So it’s as easy as, well, what is a rail? And this is an Auriel question.

Auriel Fournier:

Sure. So, you can answer that question a couple different ways. I usually answer it pretty broadly, which is that they’re members of the family Rallidae, which is a taxonomic group of birds, so that includes the gallinules and the coots and the true rails, birds that have rail in their name. But the problem with sticking with just the true rails is that they’re not all taxonomically similar, like Black Rail, Virginia Rail, and Clapper Rail are not all that closely related when you compare them to things like Sora and King Rail and stuff like that. So anyway, not to go down too much of a taxonomy rabbit hole, but broadly speaking, it’s anything in Rallidae. So they’re webless birds, they’re often called chicken-like, and many of them certainly fall into that category. Most of them are very cryptically colored, with of course exceptions like purple gallinule.

Hank Shaw:

They’re just so cool. [crosstalk 00:07:43]

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, they’re beautiful birds. Rallidae are globally distributed, so they’re found on six continents. The only one they’re not on is Antarctica. And they’re also found on many islands around the world. So they’re a family of birds that has over and over again evolved to be flightless when they encounter habitats where there aren’t many mammalian predators. So there’s a lot of different individual rail species on islands, like in the South Atlantic and all over the South Pacific. So it’s just a really interesting group of birds from a biological perspective, as well.

Hank Shaw:

Wasn’t there this trippy rail on some island, maybe in the Indian Ocean, that evolved twice?

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, that information has been coming out over the past year. So yeah, there was a species that they found in the fossil record, and then it was wiped out. I’m not going to remember exactly why; by some kind of natural disaster. And then a species that is incredibly similar has evolved on that island again.

Hank Shaw:

That is so cool.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Wow. That’s amazing.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, so they’re very good at adapting to their local environment, which is pretty cool.

Hank Shaw:

I love the whole scientific word of cryptic, which basically means, “Yeah, they’re camoed.”

Auriel Fournier:

For the most part, yeah. And it’s a behavioral thing as well, right? I mean, with the exception of things like coots and some of the gallinules that will spend time out in the open, most rails don’t like to be seen or sometimes heard, so yeah.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Do most rails have that same call that the Clapper Rail does, which is that [inaudible 00:09:13], or not?

Auriel Fournier:

Many of the North American rails have some kind of variation on that, yes.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Got it. Okay.

Auriel Fournier:

Like the Sora has their whinny. The Virginia Rail has a similar call, as well.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Right, yeah.

Hank Shaw:

I’m going to put sound files to all the different rails. And everybody who is going to listen to this podcast who spends any time duck hunting is going to be like, “Oh my God, they’re everywhere. I’ve just never seen them,” because you hear them all morning long when you’re hunting ducks.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, absolutely.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, that was one of my favorite things. So, I did my PhD research on a bunch of state and federal land in Missouri. And I would run into duck hunters a lot. And they’d be like, “Oh, you guys don’t need to go out and survey. There aren’t any rails out here.”

Auriel Fournier:

And I was like, “Slam your car door.” And they’d slam it. And I’d be like, “Those, that’s all the rails. You might not have seen them, but they’re definitely out here.” So, that was-

Hank Shaw:

They’re super stealthy. Hey, here’s a question. Is it like a rooster and a hen, or a cock and a hen, or a drake and a hen? What’s the nomenclature?

Auriel Fournier:

That’s actually a really good question. I actually just call them male and female. I don’t know if there is a general nomenclature for it.

Dave DiBenedetto:

I’ve certainly never heard of one or used one, nor do I know that I’ve seen a difference [crosstalk 00:10:27]

Hank Shaw:

That’s another question. Is there dimorphism?

Auriel Fournier:

So for things like Clapper Rail, there isn’t any plumage dimorphism; on Soras you will, like the males get that really big, black neck and face. And there is some dimorphism and plumage on Yellow Rails. But for many of the others, there isn’t. But purple gallinule would be another example where there is some strong sexual dimorphism.

Hank Shaw:

They’re related to pukekos in New Zealand, aren’t they?

Auriel Fournier:

Yes.

Hank Shaw:

Actually, I have had the privilege of hunting pukekos, and [crosstalk 00:11:00] I went on national television in New Zealand, which is kind of like being world famous in Poland, just to cook pukekos. The TV station was like, “You can’t eat pukekos.”

Hank Shaw:

I’m like, “Well, why can you hunt them, then? I mean, of course they’re going to be eaten.”

Hank Shaw:

They’re like, “There not going to be delicious.”

Hank Shaw:

I’m like, “Hold my beer.” And they were amazing. I mean, just like a coot here in this country, they’ve got these big old legs with just mega sinews. And when we get into the cooking, that’s the biggest issue with cooking these birds. And I’ll only be able to speak from the perspective of cooking the non-rail-named gallinules. But they were just perfectly fine. And they’re huge. And by the way, they talk exactly like the Velociraptors in Jurassic Park.

Auriel Fournier:

That’s pretty awesome. Yeah, the pukekos are one of the bigger members of Rallidae, so yeah, they’re [inaudible 00:11:57]. There’s a lot of dimorphism.

Hank Shaw:

Do you guys know anything about the history of hunting rails in this country?

Dave DiBenedetto:

What I know comes from reading a little bit of Audubon. And when he was doing his travels, he came through Charleston, actually. And he describes a good bit of what it was like back then. And again, it’s not that very different than it is now, besides the fact that there were no limits, and probably a lot more rails out there, because it sounds like they piled them as high as they could. So again, not much has changed when you’re rail hunting now as opposed to rail hunting then.

Hank Shaw:

Hey, I’d like to take a moment to say that Hunt to Eat is a proud sponsor of this podcast, which makes sense because I own and wear a lot of their shirts, hats, and other gear. When you reach into your drawer to grab a shirt to wear to a barbecue or a conservation event, you always grab the same one, right? Well, you’re about to find your new favorite tee. Head over to hunttoeat.com and check out their line of hunting and fishing lifestyle hats, hoodies, tees, and more. They’re super soft, they’re a great fit, and they’re designed and printed in Denver, Colorado. Be sure to check out the new line of Hunter Angler Gardener Cook apparel, and use the promo code HANK10 for 10% off your first order. That’s HANK10, and you get 10% off any Hunter Angler Gardener Cook merchandise you feel like picking up and wearing to your next event. Thanks.

I’m fascinated by the concept of it, though, because … So Dave, just walk me through a typical East Coast rail hunt. What does it look like, for people who may not know?

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah. Well, the first thing you got to know is it’s all tide-dependent, right? And as Auriel has said here, these birds don’t want to be seen. So you need to hunt on a full moon tide or a new moon tide, what we call spring tide. But those are the highest tides of the fall. And those usually happen a couple of days every month. And while rail season, say, is open for the entire month of November, you’re not going to go hunting unless you’ve got that full or new moon, and even better if there’s a northeast wind blowing more water into the marsh, because what that does is they can no longer hide in that green Spartina grass, which is about two and a half or three feet high. And they then gather into little patches of grass that are still exposed, and that can be on the edges of creeks, which are a little higher, like little tidal creeks, or we call them feeder creeks off the main river, or they may be on a rack, we call marsh rack, which is some old grass that’s matted up.

So it’s really all about the tides. And if you’ve got the right tide, then you just need a boat. And in many cases, I’m an old school rail hunter. I use the jon boat. So I get on the oars, or convince someone else to get on the oars, and row. And I’ll row down just a tiny tidal creek not much wider than the boat. And you often want to go with that last bit of the incoming tide. And as you approach some of these areas of grass that are still exposed, you’ll flush them. And even then, a lot of times, they don’t want to flush. So you can get surprisingly close, which can also make you feel like a fool when you try to shoot and you totally whiff. It’s usually two guys, two hunters in the boat, and a dog.

Hank Shaw:

I mean, that’s got to be one of the real reasons why it’s kind of a limited entry thing, at least in the East. And we’ll talk about rails, because they’re all over the country. But in the East, it’s always this boat thing, and there’s a bit of an air of mystery behind it.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah. And there’s this … I don’t know if you’d call it a myth, because I’ve tried to cook them, and we’ll get into cooking. But I don’t know that many people have discovered the right way to cook them. So there’s that, right? There’s this myth. But they can be … I’ve eaten plenty, so I’m glad that that myth persists, because I certainly don’t want to see a crowded marsh. I mean, that’s one of the most beautiful things about rail hunting, is you’re out there in the fall on that high tide, the Spartina grass has gone from green to its autumn/winter color, and you’re just floating along in this true wilderness, really. It feels like you’re on a savanna. Usually behind barrier islands, so you’re a little protected from that wind. It’s truly one of my favorite things to do.

Hank Shaw:

So Auriel, let’s get into the four main rails. I think there’s only four that you can hunt in the country. And there’s lots and lots of things that are called rails. So as far as I know, there is only the King, the Clapper, the Sora, and the Virginia, are the four that have hunting seasons somewhere in the United States. Is that right?

Auriel Fournier:

Yes. I mean, you can also hunt American coots various places. And they’re in Rallidae, as well. But yeah, for the true rails, that would be the four. Yep.

Hank Shaw:

So imagine you are on the boat with Dave, how in the world are you going to identify these birds and not shoot the wrong bird?

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, I think some of that comes down to practice. It has a lot less to do with the specific kind of colors that you see and more to do with how the bird moves, and a lot of it is [inaudible 00:17:51]. So with Clapper Rails, it’s a little bit easier because they’re so much larger than Soras and Virginias that if you spend a little bit of time out in the marsh, you’ll pretty quickly be able to tell the difference because they’re an order of magnitude bigger. For the work that I’ve done for my research, we’re going out at night and trying to count them. So a lot of it has to do with looking at leg color and looking at the birds’ body position as they fly. So when rails just pick up and fly short distances, they fly with their legs down, and so you can-

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, that’s right.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, it looks really funny. A lot of the managers I work with don’t believe that the birds migrate because it doesn’t look like they can fly very far. But so they fly with their legs down for short distances. So you can get at those different leg colors. And with a little bit of experience, you can also see that Virginia Rails frequently hold their wings pretty differently than Soras do. I mean, depending on where you are in the country, like if you’re where I am in the middle part of the country, the main thing to look out for is going to be Yellow Rails. And in that case, you don’t want to shoot something that has a bright white wing patch. And it’s very distinctive.

Hank Shaw:

Got you.

Auriel Fournier:

I think-

Hank Shaw:

It’s like with snipe, when you flush a snipe, and it’s got a white butt, that’s a dowitcher. Don’t kill it.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Right.

Auriel Fournier:

Right. So I think it’s just spending time out there before you’re going hunting, and making sure that you’re comfortable with IDs. But yeah, it just comes with some experience.

Hank Shaw:

Are there habitat differences between the two, like, oh, this is only going to have Soras, or this is only going to have Virginias, or whatever?

Auriel Fournier:

To certain extents. More so during the breeding season than you would encounter during the hunting season. Virginia Rails will tend to be in places that are a little bit wetter, and they’ll tend to be in habitat that has more vertical structure. So they would be in something with more cattails and bullrush versus something that’s more millet and smartweed dominated. But there’s certainly a lot of overlap. You’ll find them in the same places.

Hank Shaw:

Interesting. So as a California duck hunter, the only rail that I ever encounter with any frequency are Soras, and there’s absolute mega Soras in some of the places that I hunt.

Auriel Fournier:

Certainly.

Hank Shaw:

But we don’t actually have a rail season in the West, and I don’t know if you have any idea why that might be.

Auriel Fournier:

I honestly didn’t realize that, so I’m not sure why. I mean, in most Eastern states and in several of the Canadian provinces, there’s a Sora season and a Virginia season. So yeah, I’m not sure what that’s a relic of.

Hank Shaw:

It could be a case of … For example, we don’t have a sandhill crane season because we’ve got the two different kinds, the lessers and the greaters. And the Pacific flyway population of … I’m going to get this wrong, but one of them, one of them’s not so great, and you really can only tell them in hand. So it could be a deal where one of the typical rails out here in the West Coast isn’t very common, so there’s not really a huntable population of them because of habitat loss. I’m just guessing, but that would be my guess.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, it may have to do … There are some different subspecies of Virginia Rail. And one of them is out on the West Coast, and so maybe it’s because of the status of that subspecies or something, too.

Hank Shaw:

So talk to me about … If a guy in Missouri or Illinois or Ohio or in the middle of the country … And there’s a guy I’ve been in correspondence with who hunts them quite avidly in eastern Oklahoma, so that’s going to be a very different-looking pursuit than boating on the East Coast marsh.

Auriel Fournier:

Certainly, yeah. So the folks that I’ve interacted with, yeah, described a very different experience than what Dave was saying. So they’re going out and walking through … In Missouri and I’m sure in eastern Oklahoma, these moist soil, smartweed, millet, very emergent marsh situations. Many of them are working with dogs. Some folks don’t, though. And they’re covering large amounts of ground on foot, and they’re flushing birds up that way. So my doctoral advisor, David Krementz, who’s an avid rail hunter, and he would say you’d get about a bird a mile. So it’s a pretty active method of hunting. But yeah, and the folks I’ve talked to have mirrored the same experiences I’ve had in going out and trying to count them, which is you want to look for these kind of habitat edges. So they don’t like to be out in the open, but they often like to take advantage of places where there’s high amount of food resources. And a lot of times, that’s at habitat transitions, so either a transition between vegetation and water or between different kinds of vegetation is where we’ll frequently find them in higher densities.

Hank Shaw:

Interesting.

Auriel Fournier:

So you’re not necessarily walking a straight line. You might be following a habitat transition.

Hank Shaw:

That’s interesting. So Dave and I, we both had an invisible light bulb go up above our head because more or less everything that human beings hunt or fish live on the edge of something.

Dave DiBenedetto:

They love an edge. That’s right.

Auriel Fournier:

Sure.

Hank Shaw:

Really everything. Deer are edge creatures, grouse are edge creatures, fish are edge creatures. It’s kind of fascinating how that works out. So habitat is one thing. You mentioned it just briefly a second ago, diet. What do rails eat?

Auriel Fournier:

So during the spring and the breeding season, they’re primarily eating invertebrates. We don’t necessarily have a great understanding at any more precision than that for some of the species, but we know for instance that Yellow Rails eat almost primarily snails during the breeding season. But then during the fall, they’re switching over to seeds. So yeah, I mean, that’s why it’s not surprising to find them in these big stands of smartweed and millet and other really heavy seed-producing plants in the fall. They’re in there, they can gain really ridiculous amounts of weight during migratory stopovers. We would catch some individuals that were so fat that they were unable to fly.

Hank Shaw:

Oh, so good.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, given the opportunity, they can really pack on the weight.

Hank Shaw:

Do they do the steatosis thing with their livers? Do they self-foie gras their livers?

Auriel Fournier:

I am not sure.

Hank Shaw:

I guess you’d have to open one up.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, which there are folks who have done some of the dietary work, but that’s not the kind of work that I’ve done, but it’s possible.

Hank Shaw:

Because from a cook’s perspective, where I interact a lot with science and biology is I am a great reader of anything that … This is a tip for anybody out there, is if you really want to geek out on a game animal that you’re pursuing, find its Latin name, go to Google Scholar, type that Latin name in quotes, and then type this phrase, also in quotes: food habits. So you combine those two, and then it’ll spit out all of the actual science that’s been done on the food habits of X or Y creature. And in the case of something like a rail, since it lives all over the country, you’ll see somebody somewhere may have done a food habits study about rails or ducks or grouse, whatever, whatever, in your region. And that gives you a very good indication of not only what they eat, but as a guy who’s done this for, God, almost 20 years, the things that the animal that you pursue eats, if they are also edible, go well with that thing in the dish that you create.

So in other words, the seeds that … So one thing that we have here in California is we’re the number two producer of rice. So you’re never going to go wrong doing duck fat fried rice with our California ducks. And very often you’ll find that, especially in the fall when a lot of our game birds are chasing seeds. I mean, virtually every bird in the spring eats bugs or something like that, because they need the protein for the eggs, and that sort of thing. Then in the fall, a lot of them switch to fruit and nuts and seeds, which human beings in general, we like things that eat that, because it creates flavors that we like. And that’s interesting to hear about the rails, that they’re …

Another side note is there’s two ducks that are very similar superficially: the bufflehead and the ruddy duck. So they’re both very little diver ducks that are considered trash ducks by a lot of people. But ruddy ducks, their food habits are 80% seeds and vegetation. The bufflehead is 80% inverts. So they might look similar and they might act similar, but they do not taste similar. And this is a really good window into whether something is going to taste good or not. I bring all this up because rails are kind of a mystery to a lot of us. And if we know what they eat, it’s a good indicator of really, even, as simple a question as do you pluck it or do you skin it?

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, so, very interesting. Auriel, it’s my understanding that the Clapper Rails eat a lot of fiddler crabs. Is that [crosstalk 00:27:11]

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, they definitely do. Yeah, fiddler crabs. There’s been some really interesting work down on the Gulf Coast about how Clapper Rail reproductive success is tied really closely to fiddler crab population size. So yeah, it’s a really big part of their diet.

Dave DiBenedetto:

So Hank, you’re going to have to serve a side of fiddler crabs when you cook your Clapper Rails.

Hank Shaw:

That sounds like a … I mean, it’s not as bad as mergansers.

Dave DiBenedetto:

You’re right.

Hank Shaw:

But that suggests that … Number one, my first thought is, skin that sucker.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yes, yes.

Hank Shaw:

Number two is if you didn’t skin it, you might want to go with a paella and just go with what nature gave you, and put either crab meat and/or shrimp in the same dish.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Right, right.

Auriel Fournier:

King Rails eat a lot of crayfish or crawfish, or however you choose to pronounce that. So they’re also very crustacean-focused, they just choose the freshwater variety.

Hank Shaw:

Interesting. Yeah, that’s [crosstalk 00:28:06]

Dave DiBenedetto:

Crayfish on the side would be good. [crosstalk 00:28:09]

Hank Shaw:

That would. Oh, I got the dish. And in fact, I created this dish not fully knowing what you guys just told me. But in my latest cookbook, Pheasant, Quail, Cottontail, I actually have a recipe for rail purloo that has shrimp in it.

Dave DiBenedetto:

There you go.

Auriel Fournier:

There you go.

Hank Shaw:

And it makes perfect sense. I mean, I actually made it with snipe because they didn’t have any rails, but it worked just fine.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah. I mean, and the rails that are moving through the part of the country that I’m in, most of them are going down to the Gulf Coast to winter, where they’re spending a lot of time in rice. So there’s actually a Yellow Rail and Rice Festival in Louisiana every fall, because the Yellow Rails use the rice fields, so they’ve got it set up so that primarily bird watchers can come in and ride on the combines while the farmers are harvesting the rice, and see the birds, because they’re flushed out of the fields as the rice is harvested.

Hank Shaw:

Interesting.

Auriel Fournier:

And King Rails spend a lot of time in agricultural rice fields, as well.

Hank Shaw:

What about Soras?

Auriel Fournier:

I assume that they do. I don’t know if anyone’s specifically looked at it. But I’d be really surprised if they didn’t.

Hank Shaw:

They seem awful small to eat inverts, unless they’re eating very, very small inverts.

Auriel Fournier:

Right, yeah. Over the winter, I’m sure they’re primarily grain- and seed-based.

Hank Shaw:

I was doing some research for this podcast, and I think I read a story, you’re featured in it, Auriel, looking for Black Rails.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah.

Hank Shaw:

It’s like the bird that apparently doesn’t exist, except it does?

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah. They’re very, very elusive. So it’s the smallest rail that we have in North America. It’s among the smallest of rails globally. And yeah, the Eastern population is being considered for listing under the Endangered Species Act. So they’re not overly abundant, and they’re extra elusive. If you think it’s difficult to get your eyes on a Sora or a Clapper Rail, you should try to find a bird that’s black and roughly the size of a sparrow, that basically refuses to fly. But yeah, I’m really fortunate to get to work with a great group of folks down on the Gulf of Mexico on trying to better understand how to use prescribed fire to manage their habitat.

Hank Shaw:

The guys at Quail Forever do that, too.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, yeah. Prescribed fire is a fantastic tool for managing a variety of habitats, definitely.

Dave DiBenedetto:

It’s interesting, this trait that they share of not wanting to fly, which is one of the things, when you’re hunting them here, and I mentioned sometimes you can get real close. The old timers sometimes carry a bucket of oyster shells to toss in the general direction, one or two, and get them going. But they certainly like to stay tucked in. And it’s shocking how you could have maybe eight or nine strands of Spartina grass, and a decent-sized Virginia Rail, or what we call marsh hen will be in there, and you don’t see it. You don’t know it until either it pops up after you’ve gone by or the dog jumps off a boat because he can’t take it anymore, and he knows it’s there.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, they’re really good at hiding in vegetation. And Sora and Virginia Rail are also really adept swimmers and divers.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yes, right.

Auriel Fournier:

So they’ll swim with just their head above the water or sit with just their head above the water, and they’ll also dive and grab onto vegetation and sit under the water and wait for … Well, they think we’re predator … I guess if you’re hunting you are a predator. So they’re waiting for the predator to leave. So yeah, they’re very good at using their environment to stay safe.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, the Clapper Rail does that swim where its head bobs forward as it moves, which I think a lot of them do, right?

Auriel Fournier:

Yep, yep.

Hank Shaw:

Like a coot?

Auriel Fournier:

Yes, it’s very coot-like.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, like a coot. Yep, very coot-like. Yep.

Hank Shaw:

So an interesting side note to all of this is that yes, coots, moorhens, and purple gallinules, they’re all basically rails.

Auriel Fournier:

Yep.

Hank Shaw:

Are they in the order galliforms? Are they actually water chickens, or are they something different?

Auriel Fournier:

They’re in the order gruiforms.

Hank Shaw:

Okay, so they’re not actually chicken birds?

Auriel Fournier:

They’re not actually chicken birds, they just look like chicken birds, yeah.

Hank Shaw:

Okay, because it makes sense, because to my knowledge, every rail is a red meat bird, right?

Auriel Fournier:

Yes [crosstalk 00:32:34]

Hank Shaw:

Because they all migrate.

Auriel Fournier:

Yes, they do. They might not look like they can fly very well, but they take off. And the little bit of work that’s been done tracking them during migration suggests that they can go a couple hundred miles in a night. So when they get up and move, they can really go.

Hank Shaw:

Well, and coots, I believe, you would probably know better than I do, I think coots are the highest-flying migrators of all water fowl.

Auriel Fournier:

I have not heard that particular statistic, but yeah, I mean [crosstalk 00:33:02]

Dave DiBenedetto:

The highest, you’re talking altitude?

Hank Shaw:

Altitude, yeah.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, okay. That’s cool.

Hank Shaw:

So once they get up, they get up.

Auriel Fournier:

That’s really cool.

Dave DiBenedetto:

And the Clapper Rail, are they a night time migrator?

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, to the best of our knowledge, all rails are nocturnal migrants.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, I knew coots are. So I actually taught myself how to so-called duck hunt by stalking and assassinating moorhens and coots. Because I started as an adult, and nobody really told me how to hunt ducks. So I just would go to public refuges. And I knew that moorhens and coots were legal game, and nobody else seemed to be hunting them. So I took it upon myself to see if I could actually hit things with them. And I wish there had been drone footage of me sneaking up [inaudible 00:33:59], like Elmer Fudd, and then with this huge raft of coots, like [inaudible 00:34:13], and like, “Surprise, motherfuckers.” I once killed nine with one shell. So the first time I ever did it, I brought back, I don’t know, maybe four or five of them. And they look like chickens, so I plucked them. And they have beautiful white fat. It looked great. So I popped them in the oven to roast, and oh my God, it smelled like low tide on a hot day. It was not fishy at all, it was pondy, like the algae at the bottom of a pond.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Like muddy, yep.

Hank Shaw:

Yes.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, it’s a real reflection of where they are in the food chain, so yeah.

Hank Shaw:

But yeah, I mean, for the duck hunters out there, they are the best confidence decoys, because coots are super wary. And if you are hunting in a patch of cattails or whatever, and you have a bunch of coot decoys around you, then all the other birds are like, “Oh, well, there can’t be a hairless ape with a gun in that particular set of [inaudible 00:35:19]. So let’s go there.” [crosstalk 00:35:25]

Dave DiBenedetto:

But you know, there’s a sculptor down here in South Carolina, Grainger McKoy, who does amazing, amazing work. And he’s probably in his 70s now, but grew up in the Lowcountry. And we did a talk together once, and he has done some beautiful rail carvings, just tremendous. Anyway, I asked him about rail hunting and he said, “You know, the best way to hunt rails is to go out with a .410.” And he said, “You put one shell in your pocket. And when the rail pops up, you take the shell out of your pocket and you shoot.”

Dave DiBenedetto:

I was like, “Okay, well, you’re a better shot than me, but I get it.”

Hank Shaw:

Is that because they flush so close?

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yes, exactly. Yeah.

Hank Shaw:

That’s funny. I tell all my friends who are just starting to hunt, and I try to mentor a lot of new hunters, so a lot of their first hunts are at these … we call it a pet and shoot, the preserve hunting?

Dave DiBenedetto:

Right, yep. Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Hank Shaw:

So I always tell them that when that fat, pen-raised pheasant gets up at your feet, you should say to yourself, “Look at the pretty bird, raise your gun, and then shoot.”

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, that’s right. Absolutely right, but [crosstalk 00:36:35]

Hank Shaw:

I didn’t know that they flushed so close. I like the tip on feet-down, because I actually tried to hunt them in Angleton, Texas this past September. And I know I saw a bunch of them because I know I saw a bunch of feet-down, not-coot, funny-looking bird things. But not being John James Audubon, I didn’t want to ground check them by just like, “Shoot that, and find out what it is.” Because that’s no bueno. So it took me a while to figure out that that feet-down was definitely a rail.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, that’s a strong signal of a rail. Soras have more of a yellowy-green leg to them, and Virginia Rails have got a little bit more orange. And they’re both a little bit more smaller than a robin, to give folks a reference point if you are well associated with American robins.

Hank Shaw:

They are small, then. So that means they’re-

Auriel Fournier:

Yes, Clapper Rails are quite a bit bigger.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, Clapper Rails are like-

Hank Shaw:

That means they’re like a dove.

Auriel Fournier:

Mm-hmm (affirmative), yeah.

Hank Shaw:

Then King Rails must be quite big, then?

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, Kings and Clappers are very, very similar in size. You’re looking at somewhere around 400 grams for a King Rail or a Clapper Rail, whereas most Soras and Virginias are going to be under 100 grams. I’ve caught a couple of Virginias that are over that, but they were obesely fat. I’m sure at a more normal weight, they might be 100.

Hank Shaw:

Speaking of weirdly, unusually, morbidly obese birds of Walmart kind of thing, I had the opportunity to hunt chachalacas just the other day.

Auriel Fournier:

Oh, cool.

Hank Shaw:

So if you’re not familiar with the chachalaca, not only is it the coolest bird to say in North America, it’s legit a chicken. It’s totally a chicken. So, they’re Cracidae, so basically, they’re chicken cousins. But most of the so-called chicken cousins that I encounter are really grousey. This is not grousey. It is chickeny. It has yellow skin and I don’t know how it got so fat, but they were morbidly obese birds. It was amazing. [crosstalk 00:38:46]

Dave DiBenedetto:

They sound tasty.

Hank Shaw:

They are amazing. I’m going to post the recipes for them very soon. And of course, the story I’m writing about the hunt itself has named itself. It’s got to be Boom Chachalaca.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, right.

Auriel Fournier:

But of course.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Well done, well done.

Hank Shaw:

Give me a story there, Dave. Tell me about a cool rail hunt that keeps you going out there after it.

Dave DiBenedetto:

I got to say, what I’ve found so great about rail hunting, one of the things I mentioned earlier, was how beautiful this area of the country is that time of year, on that high tide, the great color. You’re the only one out there. Sometimes on these rising tides, you can fish redfish in the marsh before it gets too high, so you’re casting and then you’re moving to the blast afterwards. But I’ll be honest, my Boykin, she was tough. And when you got her in a duck blind or in a dove field, if you were shooting and nothing was falling, or other people were shooting and you weren’t, she couldn’t control herself and I couldn’t control her, and she would either eat the duck blind or dig a hole as big as a … You could bury a man in it, in a dove field. And we got out onto the marsh. And for one, it’s less pressure. Immediately, it’s less pressure. There are a lot of birds, there are not a lot of people around at all.

And I just remember early on hitting a few, then they would drop a ways in the Spartina grass, and I would think to myself, “Oh man, I wonder if she’s going to get this.” And she was made for it. She has a great nose, and I think they have a definitive scent. And just watching her work in that Lowcountry marsh, I was as proud as you could be, and as happy as you could be. And also, I’m not a great shot, so I don’t have any problem with the fact that they don’t get up like a quail. So for me, it really was that this is the thing I can do with my dog. And that is special to me. That’s what keeps me … I love hunting, but I really love hunting with a dog. So for us, it was marsh hens.

Hank Shaw:

That’s good. It makes me want to go out there and do it. And to my knowledge, there are no … Maybe you know. You can’t just go rail hunting with a guide or anything, is there? It’s all just-

Dave DiBenedetto:

You can. So some of these flats fishing guys, they’ll use a flats boat. And in Charleston, I mean, there are a lot of light tackle guides, but there are probably two or three that you could line up a hunt with. I know similar up in the Myrtle Beach area, and probably same in Savannah. People are catching on. And the thing is, once you’ve done it, you get it, how cool it is.

Hank Shaw:

Are we talking September, October, or [crosstalk 00:41:59]

Dave DiBenedetto:

It’s a split. Here in South Carolina, it comes in for about a week in October, and then it comes in mid-November to I think late December. But again, you only have maybe four to six days a month where you can actually do it, because if the tide’s not … Let’s just say a normal tide is 5’8″ from the low water mark. If you were out there on that, there’s still about 8″ of Spartina grass exposed, and you’ll never get them to flush in that. You just can’t. Trust me, I’ve tried it, and there’s just no way. And they’ll just disappear into it. So you just need those tides. And like you said, that is a limiting factor. It’s a long season, but in reality, there’s only a few days that work.

Hank Shaw:

So they don’t migrate?

Dave DiBenedetto:

Auriel, correct me if I’m wrong, I think we have some full-time resident birds, and we also get some migrants during a cold winter. Is that true?

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, that is correct. So the Clapper Rails that are farther north on the East Coast, I think from probably roughly Delaware farther north, those are somewhat migratory, depending on winter severity. But our current understanding is that the birds on the lower part of the Atlantic coast that breed there, stay there year-round.

Hank Shaw:

I do know there is a very venerable, centuries-old New Jersey Sora Rail hunting tradition.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Huh, I didn’t know that.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, so very similar to what you guys do in the Deep South goes all the way up to Jersey. And I’ve even seen some evidence of punt boat and double-ender rail hunting in Long Island, back in the early 1900s.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Wow, I had no idea about Long Island.

Hank Shaw:

I could believe it, though. I used to dig clams there and tongue oysters when I was in college. And yeah, you could see, it’s all developed now, but you have a barrier island. It’s the Great South Bay.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, that’s right. Yeah, that’s a stunning piece of water.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, it would make perfect sense back in the day, but it’s all no habitat. The guys I’ve been talking to in the center of the country … I don’t know a single Western rail hunter, interestingly. Once you get to the Rockies, it kind of disappears. But the Midwest, especially the central Midwest, where you’ve done a lot of your research, Auriel, you get them. And there, it’s a migration thing. It’s a bit like woodcock.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, exactly. So I mean, the season here is pretty long. I believe it’s two months. And we’re not restricted by the tides. So peak rail migrations, they’re most in Missouri, is in late September, early October. And yeah, you could consistently go out many days and encounter really high densities of birds, but yeah, I’ve-

Hank Shaw:

But it seems like the hunting’s much harder.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, it’s not a light exercise.

Hank Shaw:

Because yeah, if it’s a bird a mile, and you’re not [crosstalk 00:45:13] walking in a field, you’re walking in a marsh.

Dave DiBenedetto:

You’re right. I heard that same thing and I thought, “My God, the number of birds that we have in a mile, if you’re in the right place, is mind-blowing compared to that.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, I’m sure if you hit migration right on, it would probably be a lot better than that. But there’s a lot of variation from day-to-day. They seem to come and make fairly long stopovers, individual birds, in this part of the country. But then they start to leave in early October when the cold fronts start rolling through. So there may have been birds stacking up here for quite some time, but then they start to take off as those winds start blowing.

Hank Shaw:

I guess they spend their winters in Louisiana, I would imagine.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, some of them probably continue farther south. We’re not really sure what proportion stays on the northern Gulf and what proportion goes down into Mexico. They have been found on oil platforms out in the Gulf of Mexico, so we know that some of them are crossing. But there are certainly large numbers that stay in the US Gulf states for the winter.

Hank Shaw:

I guess it makes sense, because Tamaulipas and Veracruz don’t look a hell of a lot different from Texas.

Auriel Fournier:

Sure, yeah.

Hank Shaw:

Hey, everyone. I’d like to take some time to thank Filson, the original Alaska outfitter, for sponsoring the Hunt Gather Talk podcast. As you know, I am rarely out chasing upland birds without my Filson jacket and Tin Cloth chaps. You should know that Filson was founded in Seattle, Washington, in 1897, when they started fitting prospectors for the Klondike Gold Rush. And ever since then, they’ve been committed to creating the best-in-class gear for the world’s toughest people, in the most unforgiving conditions. Right now is Filson’s winter sale, and you can save at least 35% on unfailing goods, including classic bags, outerwear, boots, and more.

How much is actually known about this group of birds? I mean, you talk to people who are grouse hunters and pheasants and quail, and there’s quite a lot of science behind those birds. And I get the sense that not so much with rails.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, so there was quite a bit of work done back in the ’60s and ’70s. Then it kind of dropped off. And part of it was technologically limited. So to do surveys for these birds here in the breeding season, unlike, say, for waterfowl, where you can chart them from an airplane, or songbirds, where you can go out and do point counts pretty easily, where you listen for them, for these birds, you have to go out, and to greatly increase your chance of detecting them, you broadcast their call to try and get them to call back to you. And that whole protocol was really designed in the late ’90s, early 2000s by a researcher who’s now at the University of Idaho named Courtney Conway.

So now that we have that protocol in place, monitoring for these birds has really expanded over the past decade. So we have a lot better idea of what kind of habitats they’re using, what their distribution is. We’re starting to get a handle on population numbers. And there’s a lot more graduate work being done trying to better understand their food habits and how to manage for them in different ways. So yeah, it’s really growing a lot, even since I started my graduate work eight years ago. So it’s really an exciting time to be working on them, but it’s very different than bobwhite or grouse, which we’ve had huge amounts of information on for decades.

Dave DiBenedetto:

The thing about that call, I love that, too. I mean, when you’re out there and one of them calls, [inaudible 00:48:45], and then the whole marsh just lights up-

Auriel Fournier:

It’s amazing.

Dave DiBenedetto:

… you realize how many are around you that you can’t even … You’re like, “Oh my God, they’re all over the place.” But good luck trying to see them. But that call-

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, and I would assume that they respond to a shotgun being shot. I mean, they certainly respond to car door slams and to ATVs backfiring. Any kind of a sharp noise can really set them off, so that’s pretty cool.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, that’s right. So when my son was young, I used to walk him in the morning down this park, right along the edge of this big stretch of marsh. And it wasn’t a word, but one of his first things he did was [inaudible 00:49:25], because-

Auriel Fournier:

That’s fantastic.

Dave DiBenedetto:

… I would always say, “Those are the marsh hens,” and I would do my imitation. So I was quite proud, as a dad.

Auriel Fournier:

That’s very cool.

Hank Shaw:

They’re like turkeys, like that.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yes.

Hank Shaw:

Turkeys will do the same thing.

Dave DiBenedetto:

That’s right.

Hank Shaw:

In fact, a crow call is my secret weapon with finding turkeys where I can’t find turkeys.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Right, a crow and an owl.

Hank Shaw:

Oh, that’s right. I heard about the owl. Part of this whole thing is I’m gathering information from you guys as I talk to you, because I am on a bizarre, quixotic quest to hunt, shoot, and eat every small game animal that has a season and a bag limit in North America. And the rails are the only major gap I have left in this whole thing of mine. There’s maybe a dozen species, maybe a shade more if you include some of the duck species, that I have yet to chase.

Dave DiBenedetto:

That’s sounds like an enviable assignment you’ve given yourself.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, it’s pretty cool, because you can-

Dave DiBenedetto:

Nice work.

Hank Shaw:

Because people have done the big game slam, but I’m like the anti-big game hunter. I mean, sure, I hunt big game, but Jim Shockey, I am not.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Right. Right, thank you.

Hank Shaw:

But if everybody’s going to try and go for that North American big game slam, you know what? I’ll zag. I’ll go for the … Sign me up for the rails and the snipe and the Arctic hares and the marsh bunnies. Marsh bunnies is another one I’ve got to go after, those crazy, big rabbits with the short ears?

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah. Well, that quest is going to take you to a lot of really cool habitats, too. The places that you’ll get to explore will be really fantastic.

Hank Shaw:

Exactly, like the chachalacas. I just knocked them off the list this year. And the only place that they live in the United States is basically Brownsville.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Really?

Auriel Fournier:

Which is a really cool area.

Hank Shaw:

It is.

Auriel Fournier:

I’ve spent a lot of time down there. It’s great.

Hank Shaw:

There were rails there, too. But again, I need to work on ID so that … I think that’s probably one of the biggest obstacles for somebody who wants to get into this is you really have to know your birds.

Auriel Fournier:

Yes.

Dave DiBenedetto:

I will say, it’s a little easier down here. We are generally Clapper Rails. You’ve got your smaller marsh bird, I don’t know what they call them, songbird-ish, the redwing blackbird. Then there’s a smaller heron, I think it might be the green heron-

Auriel Fournier:

Probably.

Dave DiBenedetto:

… that right as it gets up, you could make that mistake. But if you take a beat more, you realize. It sounds like you need to come to the Lowcountry, Hank.

Hank Shaw:

I’ll be there, man. What, so you think October is the time to go?

Dave DiBenedetto:

November [crosstalk 00:52:12]

Hank Shaw:

November, even better. November’s perfect because September and October are really big upland periods, and I’m often wandering through the Great Plains or something like that in that period. And November’s kind of terrible for ducks in California, so I think I’ve got a November thing [inaudible 00:52:32]. So, let’s talk about cooking them. So, I think we’ve already determined that there could be some circumstances where you might want to pluck them, but we’re not sure yet. Because if they’re eating crustaceans, chances are even if they are morbidly obese, they’re going to be kind of stinky.

Dave DiBenedetto:

That’s my take. I once tried to parboil them. I’ve tried every which way, and my wife and I tried that. And as soon as the little carriage house we were living in at the time started to smell like an old mullet, that didn’t go over so well.

Hank Shaw:

And not even a young mullet.

Dave DiBenedetto:

No, an old, musty mullet. Yes. Skinning, for sure. We’ve also drenched them in butter, soaked them in buttermilk overnight. The things that I come back to are what you’d expect. And if I was a better cook, this repertoire would probably be more expanded. But your poppers, certainly I’ve fried them and they’re good. I’ve heard people talk about, as you mentioned, a purloo or a fricassee. But the joke is down here, pay someone to clean them and pay someone to eat them, which is fine with me, because I hope people believe that. The less people hunting, the happier I am, to be sort of selfish about it.

Hank Shaw:

Have you ever eaten them, Auriel?

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, I’ve had them in gumbo, which is really good. And I’ve also had them, yeah, in poppers or bacon wrapped. That’s been Soras and Virginias. I haven’t had a chance to try Clapper Rail yet.

Hank Shaw:

So I can tell you my experience with the non-rail rails. So I have hunted, cooked, and eaten coots, moorhens, purple gallinules, and pukekos. If they’re anything like the true rails, they are often fat, but yeah, the skin’s not so good, and the breast meat’s fine, but it’s small.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, especially on Sora or Virginia, because you’re talking about a much smaller bird.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah. I mean, coots are [crosstalk 00:54:42] big.

Dave DiBenedetto:

And the Clapper Rail is so thin. It’s amazing how they can compress them. They are a thin bird.

Auriel Fournier:

And depending on who you believe, that’s where the phrase thin as a rail comes from.

Hank Shaw:

Oh, what’s [crosstalk 00:54:55] theory?

Auriel Fournier:

The other theory is that it has to do with fences, which is just a rail fence, which that’s just a very boring explanation, because obviously, the bird is awesome.

Hank Shaw:

I would think it’s the bird.

Dave DiBenedetto:

I’m in the bird camp. And honestly, I hadn’t thought about that, but now I love that phrase.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, they’re laterally compressed, so they’re compressed in from the sides, which helps them to wiggle through the vegetation and not be seen.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yes, right. Right, yep.

Hank Shaw:

Are there any other myths and lore and legends involved with rails? Do you know anything, Auriel?

Auriel Fournier:

I’ve been told that the name rail comes from a Norse word, [foreign language 00:55:31], which means to rattle. And the water rails in Europe make a rattle sound. But yeah, other than that, there’s many different indigenous people around the world who have different stories and relationships with different rail species, but I can’t remember any of them off the top of my head.

Hank Shaw:

I suspect that there was a rail hunting tradition in Europe prior to Europeans showing up here.

Auriel Fournier:

I would guess so, but I’m not familiar with it.

Hank Shaw:

Because if you think about it, prior to a shotgun, how would, say, the indigenous groups in the United States chase rails, if they even did?

Auriel Fournier:

They might have been able to build traps for them. Walk-in traps, even without the audio lures that we use today, can be quite effective if you set them up correctly. And they could have easily built them without the metal that we use now.

Hank Shaw:

Have you ever heard of the old story about the Native groups would … I’ve talked to some friends of mine who are tribal members, and half of them say it’s horse shit, and half of them say it’s true, that they would cut out a jack-o’-lantern, and they’d stick it on their head, and they would get in the marsh, so you got the eyes in the jack-o’-lantern, so you can see where you’re going, but basically, it’s a freaking pumpkin head just over the thing of water, right? And ducks, being super curious, are like, “Hey, what the hell’s that pumpkin head in the middle of the swamp?” So the Native guy who’s looking through the eye holes of the pumpkin would get closer and closer and grab them by the feet and be like, “I got you.” So I heard this story, and I want to believe it’s true.

Dave DiBenedetto:

I’m calling horse dung.

Hank Shaw:

I really want to believe it’s true, but I have my doubts.

Dave DiBenedetto:

That’s your Halloween costume for next year, a rail hunter.

Auriel Fournier:

There you go.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Wow. I believe they could have caught them, I do. During a low tide, do they travel paths in that Spartina, or-

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, there definitely seems to be some repetition to the paths that they take. There are some folks who have had good luck putting up trail cameras and actually getting some really interesting photos even of Black Rails and Yellow Rails in tidal wetlands.

Dave DiBenedetto:

What’s also amazing is the way they nest, at least the Clapper Rail. I’ve only seen one nest, but it’s sort of mind-blowing how it’s up on the Spartina and above the tideline.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, they’re really clever, how they build it. And they do the same thing in freshwater, even when they’re not dealing with tidal forces. They build these little platforms, or at least the true rails do. The coots and the gallinules more nest on mounds on muskrat huts, and stuff like that. But yeah, they’re quite adept. The Virginia Rails will often have an overhanging roof to them. I know some of the other rails do that sometimes, but Virginias do it pretty consistently. And they’ll sometimes even have a little ramp built so they can run up and …

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, it’s amazing. It’s amazing, though, to think that they survive … A storm, a super high tide, a rough day when the waves are coming in the marsh, it’s just hard. You look at that nest and you’re like, “Wow, how does that” … Yeah, it’s [crosstalk 00:59:01]

Auriel Fournier:

It is remarkable. It probably helps that they have what are called precocial chicks, so just similar to ducks, their chicks can get up and move around in the world pretty quickly after they hatch, unlike with songbirds, or something, so they’re not in the nest as long.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Got it. Okay, I didn’t know that.

Hank Shaw:

I’m pretty sure every single game bird … Well, maybe the doves. Maybe not the doves and pigeons. But every other game bird that we hunt has precocious young.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah. I’m running through stuff in my head. That sounds about right. But yeah, you are correct, doves and pigeons don’t have precocial young. They’re born with the ugly little featherless chicks that get cuter over time.

Hank Shaw:

They take a while to get cute.

Auriel Fournier:

They do. They really do, whereas rail chicks pop out and they’re just these adorable little cotton balls, most Rallidae chicks are very dark in colors. Lots of them are black.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yes, right. [crosstalk 00:59:55]

Auriel Fournier:

Coots have the ones with little weird yellow and red little mohawks and stuff. And there’s actually a really neat paper that came out, I think it was late last year, but coots have these really big broods. And the adults, depending on the amount of resources available in a given year, decide after they hatch how many to raise, and they actually use the vibrancy of the color on each individual chick to pick who to feed.

Hank Shaw:

So it is a popularity contest?

Auriel Fournier:

It’s a little brutal, but-

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, wow.

Hank Shaw:

“You’re ugly, you don’t get food.”

Auriel Fournier:

That’s kind of what happens, yeah.

Hank Shaw:

That’s pretty crazy.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Is color any indication at all of, I don’t know, strength, vitality? I don’t know, is there any correlation to the brightness, or has that not been studied?

Auriel Fournier:

I would have to go back and re-read the paper. I don’t recall if color was correlated with anything that they measured other than the ones the parents picked.

Hank Shaw:

What is a coot’s biggest enemy? I’m sorry, not a coot, what is a rail’s-

Dave DiBenedetto:

Sounds like Hank Shaw, Hank Shaw 20 years ago.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, seriously. Seriously. Who are rails’ main enemies?

Auriel Fournier:

So for the smaller rails, Soras, Virginias, things of that nature, raptors are probably a big one. I’ve seen them taken out by harriers and red-tailed hawks and great horned owls and barred owls at night. For the young, it’s probably a wider suite of things. It could be snakes and otters and mink and all-

Dave DiBenedetto:

Raccoons.

Auriel Fournier:

… Yeah, raccoons. All the things that are out in the wetland, because it does take a while for the young to be able to fly. But for things like coots, I would think once they’re fully flighted, there’s probably not a lot of things that really are a threat to them.

Hank Shaw:

Oh, I could tell you exactly who hates coots. It’s every raptor on the planet, especially bald eagles. [crosstalk 01:01:49] You can watch them all day long, and it’s super cool because there’s often ducks in with the giant rafts of coots, and these raptors will come after them and harass them and harass them and harass them. And sometimes, the whole raft gets up and lands right in your decoys. Then the ducks go with them, and that was a poor choice on their part.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Down here, the Clapper Rails, lately, there are a bunch of osprey cams that people have put up in the spring. And it’s shocking how many Clapper Rails get eaten by osprey, that you see in the nest. It’s like, “Wait.” It’s not surprising, but it’s the first time I’d seen it.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, that’s news to me. I always thought they just ate fish.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, no, there’s plenty of Clapper Rail bodies hanging around the osprey nest.

Auriel Fournier:

During migration, a lot of the rails will end up in cities. We’re not entirely sure why they seem to end up in cities so frequently. But a lot of Sora and Virginia Rail legs have been found in peregrine falcon nests in Minneapolis and Indianapolis [crosstalk 01:02:57] and Chicago and stuff. So yeah, they definitely get picked off, especially probably when they’re in a downtown area and have no idea what they’re doing.

Hank Shaw:

That seems like a poor habitat.

Auriel Fournier:

It is, but it happens pretty consistently. I mean, folks send me photos of rails in strange places, like hanging out on balconies in New York City. There was a Yellow Rail that was found in Wrigley Field a couple months before they won the World Series, just-

Hank Shaw:

See, it was an omen.

Dave DiBenedetto:

There you go.

Auriel Fournier:

That’s what I say, but folks don’t really [inaudible 01:03:27] to that too much. But yeah, during migration, they certainly end up in strange spots.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Auriel, I got to know, do you have rail art in your home?

Auriel Fournier:

Oh, I definitely do, of a wide variety. Some of it is old prints, like Audubon-style or some of the game bird-style prints that were really popular back in the ’60s. Yeah, so prior to being in Illinois, I lived down in Mississippi in Ocean Springs, and Walter Anderson is an artist who lived there.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Oh, yeah. Right. [crosstalk 01:04:02]

Auriel Fournier:

And I have some of his prints of gallinules and bitterns.

Dave DiBenedetto:

That’s great.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, whenever I find rail art, I snag it up, because it’s not overly common.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Hank, do you think you could get a rail mounted? Is there any reason you couldn’t, a Clapper Rail?

Hank Shaw:

The only reason you couldn’t is if it was hot and the feathers would slip. But I guarantee you could get one mounted, if you had a little cooler with you when you were there.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, I [crosstalk 01:04:31]

Auriel Fournier:

My graduate advisor had a purple gallinule and a King Rail and a Sora mounted in his office, so [crosstalk 01:04:39]

Dave DiBenedetto:

I’m not huge on taxidermy, but I just think a Clapper Rail mount, yeah, I would love it, just picking, poking along.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, they’re beautiful, beautiful birds. I mean, a lot of folks ignore them because they’re just boring and brown, but there’s a lot going on there.

Hank Shaw:

So before we go, you’ve already said .410s, real light guns, because they’re not real big birds.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Down here, because the salt will just destroy your gun, as you know. I bought a 20-gauge, an old Mossberg pump, at a pawn shop for like 150 bucks, and it’s perfect. It’s everything you need. Some folks do use a .410, but I’m not that good of a shot.

Hank Shaw:

That’s a good chip on the salt water.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Oh, man. It’s just good. I don’t bring my duck guns out; no matter what you do, as you know. I mean, you’ve got a dog in the boat, you’re rowing. I mean, the guns get salt. They get salted. So it’s a little easier to take with the Mossberg.

Hank Shaw:

I can’t think of any other gear you’d need.

Dave DiBenedetto:

No, that’s it. I mean, and just a box of shells. It’s surprising to me, but you don’t even need steel shot, unless you’re on a wildlife management area. Otherwise, you use lead. And that’s it. A dog helps for the retrieves, but-

Hank Shaw:

I would imagine either steel 7s or lead 8s, right?

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, exactly. Exactly. Right, yeah. And that’s it. As you said, the boat’s the real barrier to entry. But I do it out of a jon boat with a nine horse Evinrude and two oars. So it’s not like you need a fancy flats boat.

Hank Shaw:

And I suppose inland, all you need are hip waders?

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, it would be pretty simple.

Hank Shaw:

Because I mean, correct me if I’m wrong, in an inland marsh, if you’re doing all that walking, if you’re in past your ankles, you’re not in rail country, are you, or do they like deeper water?

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, you’ll occasionally find them in deeper water, but generally speaking, yeah, they’re going to be ankle deep or more shallow. But if you’re walking, you’re going to be pushing birds, and you could certainly push them deeper. But generally speaking, yeah, you wouldn’t spend a lot of time in deeper water.

Hank Shaw:

Well, I’m going to get after it this coming season. And I’m going to see if I can get all four in one year. We’ll see. That’s kind of a tall order, but you never know. And I will report back on my cooking experiments.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Come see us.

Auriel Fournier:

Please do, please do, yeah.

Hank Shaw:

So before we go, is there anything that you guys think that the listeners out there need to know about rails that we’ve not already covered?

Auriel Fournier:

I don’t know, I just always tell people that if they’ve spent time in wetlands, you’ve probably spent time with rails. And once you start listening for them, you’re going to realize that they’re everywhere. So just enjoy them.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yes, and exactly to back that up, they live in the most beautiful environments. It’s just a pleasure to be out there with them.

Auriel Fournier:

Definitely.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, I’m glad to hear you guys say that, too, because as a duck hunter, I really love just being in the marsh. Yes, I like duck hunting, but I just like seeing all the crazy things that happen to live in marshland. And a lot of people who aren’t familiar with these kinds of environments treat them as waste places and places where nothing happens, and nothing could be further from the truth.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Amen, amen.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, it’s a huge shame. Yeah, I think anybody could enjoy a wetland, regardless of how they spend their time there. They’re just fascinating places.

Hank Shaw:

Just wear good boots.

Auriel Fournier:

Exactly. Dry feet definitely helps.

Hank Shaw:

Oh my God, yes, and waders that don’t have a leak in the crotch.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yes.

Auriel Fournier:

Yes, also a huge help.

Hank Shaw:

That’s so bad, especially in December, and just a bare leak? It’s like drop, drop, drop. “No!” Because you know you’re going to be out there for six hours, and it’ll suck by hour four.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, and then your entire leg will be wet.

Hank Shaw:

No bueno. Well, all right, Auriel Fournier of the University of Illinois; go Illini. I’m a Badger, so I’m going to give you … I don’t actually hate Illinois. I hate Michigan with the heat of a thousand suns, and I hate Ohio State almost as much, mostly because Ohio State always botches it for the Big Ten when they get to the big game. And South Carolina, I don’t know, I guess you guys got Clemson, and they were good for awhile.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, I’m a Georgia boy, so I went to the University of Vermont, but I’m a Bulldog fan. So we almost get there, but we never quite finish.

Hank Shaw:

Georgia, you’re the Badgers of the SEC.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yes.

Hank Shaw:

Good, we’ll get you close, just enough to rip your heart out.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yep, and then they’ll break your heart.

Hank Shaw:

Well, take it easy, guys. I really appreciate it. We have managed to talk for over an hour about one of the more obscure game birds in North America. And I’m going to put all kinds of links in the show notes, and you guys both have my email address. Send me stuff that you think that just would be fun and interesting esoterica on these crazy birds, and I will be happy to post it up.

Auriel Fournier:

Sounds [crosstalk 01:09:59] do.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Yeah, definitely post the call, the Clapper Rail call. It’s just the coolest thing to hear.

Hank Shaw:

Oh, I’m going to do all of them. I’m going to even do the coots, because the serenade of coots when you’re duck hunting, that’s the sound of my winter.

Auriel Fournier:

There you go. [crosstalk 01:10:15]

Hank Shaw:

Well, all right, guys. Take it easy. Thank you for being on the show. And I will definitely be heading to the Lowcountry in the fall. You can bank on that.

Dave DiBenedetto:

Excellent. Thanks for having us.

Auriel Fournier:

Yeah, thank you so much.

Hank Shaw:

Well, that’s it for another episode of the Hunt Gather Talk podcast, sponsored by Hunt to Eat and Filson. I am your host, Hank Shaw, and I really hope you enjoyed geeking out over a bird chances are most of you have never even thought about hunting, let alone hunted. I hope this podcast has given you some inspiration to go out there into the marsh and get wet and chase these crazy little birds next season. Until then, you can follow me on social media. I am on Instagram all the time @huntgathercook. I am also on Facebook, where I have a private Facebook group called Hunt Gather Cook. You have to answer some questions to get into the private group, so just tell me that you heard about the group through the Hunt Gather Talk podcast.

Also, you can find thousands and thousands of recipes for every sort of wild game, fish, foraged, mushroom, you name it, on my website, which is Hunter Angler Gardener Cook. Hunter Angler Gardener Cook is the core of what I do. I am on that website every single day making it better, providing more recipes for anything that you bring home from your outdoor adventures. Again, I’m Hank Shaw. This is the Hunt Gather Talk podcast. I really appreciate you listening. Until next time, take it easy.

Struck by your comment that they might be the highest-flying migrating waterfowl. Do these guys migrate higher than the bar-headed geese, which have been tracked crossing the Himalayas while flying over 23,000 feet above sea level?

Thanks for the information and stories. I did my first sora rail hunt in Wisconsin yesterday as a way to get the dog out. It was super fun. I wasn’t as wet as the dog, but definitely wet. Just walking a wetland edge. Great work for the dog. I shot one that the dog bumped, and once she realized that we wanted them, she worked hard for them. The soras can move fast, apparently. She was tracking them through the vegetation and across shallow water. It was a bit like following a running pheasant, only wetter. I never saw them until they flushed. Not easy shooting despite being slow and close because we were in some thicker willow at times. We flushed five in an hour and I got three.