As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Lye. Isn’t that the stuff the Mafia uses to dissolve the bodies of those who’d made an unfortunate choice to use another waste disposal or vending machine company? Isn’t it drain cleaner, a deadly poison? So how on God’s Green Acre can lye be useful in the kitchen?

Relax. I am here to tell you that lye can be your friend, especially when it comes to curing green olives. Good lye cured olives, I have discovered, are uniquely smooth and luscious in a way that brine or water-cured olives can never be. Done right, they can be <gasp!> even better than a brine-cured olive or an oil-cured olive. Seriously.

Let me start by admitting that I was as terrified about using drain cleaner to cure olives as you are. Intellectually I knew it would work, and knew I’d eaten lye cured olives before, as have most of us: They are those nasty black canned things also known as Lindsay olives. That knowledge, however, did not bolster my desire to do any lye curing anytime soon.

Then I did some research. I’d seen all sorts of references to how the lye cure — actually a cure in water that had percolated through wood ashes, which are a source of lye — being used “since Roman times.”

Many hours of searching later, I found that the Roman agricultural writer Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus Palladius is the source of this, in his De Re Rustica, written in the 300s.

“Mix together a setier of passum, two handfuls of well-sifted cinders, a trickle of old wine and some cypress leaves. Pile all the olives in this mixture, saturate them with this paste in garnishing them with several layers, until you see it reach the edges of the containers.”

Passum is freshly extracted grape juice, so the lye in the ash-water interacting with this would make an interesting brew. There would be so much sugar going on in there that you could get both a lye cure and fermentation going at the same time. Freaky.

Since then the Spanish have been masters of lye cured olives. Most Spanish table olives are cured at least in part with lye, but their process is far different than that used in to make the hideous Lindsay olive. I am modifying a method I found in an agricultural book written in 1817.

Incidentally, other popular modern olives that use a lye cure include the French lucques, Italian cerignola and Spanish manzanilla.

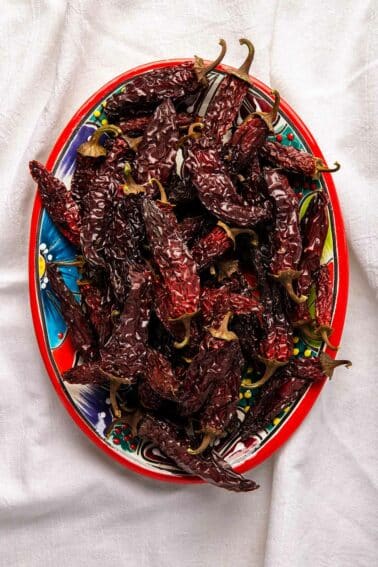

First thing you need to know about lye cured olives is that you must use fresh green olives. Not black ones, not half-ripe ones. The lye process softens the meat of the olive, so you want it as firm as possible.

When you are picking your olives, watch out for olive fly. The larva of this nasty little bug burrows into an olive and eats it from within. Thankfully infested olives are easy to spot: They will ripen faster than healthy olives, and there is a tell-tale scar on the olive that looks like this:

Toss that olive. While the worm is not poisonous, I prefer my olives sans extra protein, thank you.

What sort of lye do you use? The traditional brand to use is the classic Red Devil Lye, which is an old brand of drain cleaner. Drano used to be this way, but apparently has additives now. Don’t use it.

I now buy food grade lye because, well, it’s easy to get on Amazon, and I also like making pretzels at home, too, and they use lye to get that signature crust.

Isn’t lye a deadly poison? Sorta. Sodium hydroxide is one of the nastiest bases we know of; a base is the opposite of an acid. On the PH scale, distilled water is the median, at 7. Your stomach acid’s PH is about 1 1/2 — enough to burn a hole through a rug. Lye’s PH is 13.

Bottom line: Raw, pure lye will burn the hell out of you, but it is not a systemic poison. That means that even if you eat an olive that still has a lot of lye in it — as I did — all you will taste is a nasty soapy flavor. If you eat a bunch of them, the alkaline PH in the olives will counteract your stomach acid and it might give you indigestion. That’s all, and that’s a worst-case scenario.

That said, you need to be careful at that one moment you are moving raw, pure lye from the container to the crock you are curing into.

LYE CURED OLIVES STEP BY STEP

Follow these instructions and you will be fine:

- Wear glasses if you have them. Wear long sleeves and pants and closed shoes. You will probably not get lye on you, but better to be safe.

- Pour 1 gallon of cold — not tepid, not hot, but cold — water into a stoneware crock, a glass container, a stainless steel pot, or a food-grade plastic pail. Under no circumstances should you use aluminum, which will react with the lye and make your olives poisonous.

- Using a measuring device that is not aluminum, add 3 tablespoons of lye to the water. Always add lye to water, not water to lye. A splash of unmixed lye can burn you. Stir well with a wooden spoon.

You’re done. You use cold water because the reaction between lye and water generates heat, and the hotter the lye-water solution, the softer the olives will become. Now that it is mixed, the lye solution can’t hurt you, so go ahead and add your olives.

Stir them in with that wooden spoon and put something over all the olives so they do not float. This is vital. Olives exposed to air while curing turn black. Don’t worry, they will absorb the water and sink in a few hours, but to start you need to submerge them.

Let this sit at room temperature for 12 hours. The alkaline solution will be seeping into the olives, breaking the bonds of the bitter oleuropein molecules, which then exit the olive and go into the water. After 12 hours, pour off the solution into the sink. It should be pretty dark in color.

Quickly resubmerge your olives in cold water. You want to minimize the exposure to air. You now have cured olives.

I know, I know, a lot of recipes say to repeat the lye process another time — sometimes three more times — but that will destroy a lot of flavor; there are a ton of water-soluble flavor compounds in an olive that the lye solution washes away. Trust me. Your olives, unless they are gigantic, will not be overly bitter even after just a light, 12-hour lye soak.

Now you need to cleanse your lye cured olives. They will have a fair bit of lye solution within them now. Keep changing the water 2 to 4 times a day for 3 to 6 days, depending on the size of the olives. After 2 days, taste one: It should be a little soapy, but not too bitter. It’ll be bland, and a little soft. Once the water runs clear you should lose that soapy taste.

Time to brine. If you have large olives, make a brine of 3/4 cup salt to 1 gallon of water. And use good salt if you can. You will taste the difference. Kosher salt is OK, but ideally use a quality salt like Trapani, which is from Sicily. It’s not that expensive, but it is worlds better than regular salt.

Let the olives brine in this for 1 week. Keep them submerged, or you will get darkening. After a while they will sink. After 1 week, pour off the brine and make a new one, only this time, use 1 cup of salt per gallon.

Now you can play. The traditional Spanish cure would add some vinegar to the mix, as well as bay leaf and other spices. I’ve played with adding a touch of smoked salt, chiles, black pepper, coriander, mustard seed, garlic — think Mediterranean flavors.

But before you do this, taste your freshly brined olives. It will be a revelation. They will remain beautifully green, unlike brined olives. Salty, olive-y and very, very buttery. This is the Lay’s Potato Chips of olives. I dare you to eat just one.

Hi Hank,

It’s going to be extremely difficult for me to soak my olives in lye for only 12 hours due to my schedule/life. What are your thoughts on 18 hours up to 24? Too much?

Or, how long do I have to cure them once they are harvested? I feel that they were picked on Thursday/Friday and I received them yesterday (Monday). Do I still have a few days to lye cure them? If so, I can hit the 12 hour window. Thanks and your help is much appreciated!

Brian: That time in the lye cure is important — too long and it will make your olives mushy. I’ve cured them up to a week after harvesting.

Thank you! Also once the lye process and brining is complete do i pack them with brine or olive oil? In the past when they’ve been gifted to me, they’ve been packed in olive oil, herbs, spices and such.

Hi hank! I am buying 20 pounds of green olives. Do i need to adjust the amounts of water and lye? This is my first time and you don’t specify the weight of the olives for your recipe.

Tammy: Yes, you will need to adjust it. You need the water to cover the olives, so that will be your guide. Measure it as you do it, so you know how much you need.

Hi Hank

It’s me Denise, from Corning. The stupid Olive Farmer. My Olives are starting to turn color, I believe it’s time to harvest. Excited and worried.

Denise: Yep, time to harvest!

I loved your “how to cure olives” articles, it was fun to read.

I live in San Diego, California. I found Chaffin Family Orchard, Oroville, CA. They sell green and black olives online when is the season which is going to be after September.

Do you recommend me this one? or any other orchard I can buy online.

Thank you 🙂

Hi! I may have screwed this up. I stored my cured olives in the brine on my counter, but it now appears there is a layer of mold on top of the brine water. Are they ruined or can I toss the brine and make new–then refrigerate?

They should be fine. Make a new brine and put in the fridge. mold happens.

Thank you for your enthusiasm and olive-curing recipes. I have Mission Olive trees in my yard. In the past I ‘ve let squirrels take the fruit; this year there has been a population crash in squirrel-world so some olives remain. I want to try out, small-scale, the curing process. These once-green olives are now black (or perhaps purple). Does your recipe for curing black olives refer to these senior citizens that have changed color with age, or to some separate species of “black” olive?

John: Every olive turns wrinkled and black eventually. For a lye-cured olive you need to do it early, like September or October.

I’ve wanted to try this for years. Do you have any recommendations as far as jarring/storing them? Probably common knowledge to some, but I’ve never done it. Thanks!

Krista: I store them in brine in a jar in a cool place, normally the fridge.

Thank you Hank, your article is very helpful!

Will try my first lye cure on some green Portuguese olives next year. This year i am brine curing Galega (a mediterranean variety), maybe i could still get some ripe (dark) ones and try to make an oil-cured batch, since that process also caught my attention.

I cured manzanilla olives for the first time this year. I think I used too much lye because my olives turned out a little too soft. Not firm. They tasted so good, but everyone noticed that they were soft. I’m getting more next year to try again. Anyone with advice, I’d really appreciate it.

Also I’m getting some black olives very soon. I think I read that I shouldnt use the lye process. Is that true?

Help…

Dyan: Yes, that’s true. Don’t lye cure black ones. Brine cure them.

Brings back memories of parents doing that recipe 50 years ago… always amazed we used lye. Scavenged the olives at locations around San Jose, Ca. Nobody wanted them. Hard work,but worth it. So good. We made 4 big crocks and jars just disappeared. People I tell that story don’t believe me. I tell them I’m not LYEING !!

I love your method and have followed for three years now. But want to point out the ratio between olive to lye solution is important as well. As in, one gallon of lye solution will easily debitter a quart of olives, but if you use a gallon of solution to barely cover several quarts of olives then they are likely to still be bitter after twelve hours. If you are curing 50 plus pounds of olives you are going to be making gallons and gallons of lye solution. I typically do about two gallons of olives covered with 3 gallons lye in a five gallon bucket increments.

Thank you for the info on olives. I like having confirmation on the whole lye thing and your blog is invaluable!

Remember the Andy Griffith Show when Barney was giving away Aunt Bea’s ‘Kerosene Pickles’ as good driver awards? My friend made way too many jars of olives and we joked that she was just like Barney; they were not that good as she was afraid of lye!

How many pounds of olives will 1 gallon cure?

We do Olives this way. Nobody told me hold to can them. I am trying 4 -16oz jars in my pressure canner. Any ideas.

What a trip… and I just put my olives into the lye mixture…

Thanks again for your commitment and dedication to readers. Should I tweak the water soaking/changing time too or just taste for the soapy flavor after several days?

Matt: Just taste for soapiness.

Hi Hank…I went a little crazy on the olives this year, partially because the Farms got my orders crossed and double my order! Good problem to have, I suppose. So now I’ve moved on to the lye cured olives after already making the water cured and brine-cured varieties from your recipe, in hopes of staggering their ready dates—lye, water, brine.

Thanks for your help on the other olives. Now, I have a bunch of the big-daddy, super colossal Sevillanos ready for their lye bath. How long would you suggest these sit in the lye cure? You said maybe more than 12 hours in the article, but I wanted to see if you could suggest a time (or more concentrated lye solution) for olives that are a little smaller than a bantam chicken egg. Let me know if you have a guesstimate, as it’s likely to be more informed than mine.

Thanks!

Matt

Matt: Keep the same concentration, but double the time.

I sill make the 10 hour drive from my home near Newport, OR to Turlock, CA to pick my father’s three trees. He used the UC Davis recipe that appears to mirror your own. We cut into the olive with a sharp knife, sliding the sharp blade such that it cuts deep enough to expose the pit. When you do this, you can actually see how far into the meat of the olive the lye solution has penetrated. I’m surprised you did not mention this since you do allude to differing sizes of olives. This is the secret to knowing if you should stop the reaction or to let it continue for another couple hours. The trick is to catch the penetration just before it reaches the pit, because that’s when the olives become soft. There will be a very narrow “white” ring surrounding the pit when it’s time to stop the reaction. If the meat is dark all the way to the pit, mushy olives. But too far from the pit and you have bitter olives. It’s a bit of a dance. I usually wind up with a 14 hour soak. Love that you put this up for others to enjoy! Ciao!

My olives have dark spots on them. Why?

Steve G: Pretty normal. Little dots? If it’s big splotches, that is bruising. It happens a lot when olives are shipped. They are surprisingly delicate. They are still edible.