As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

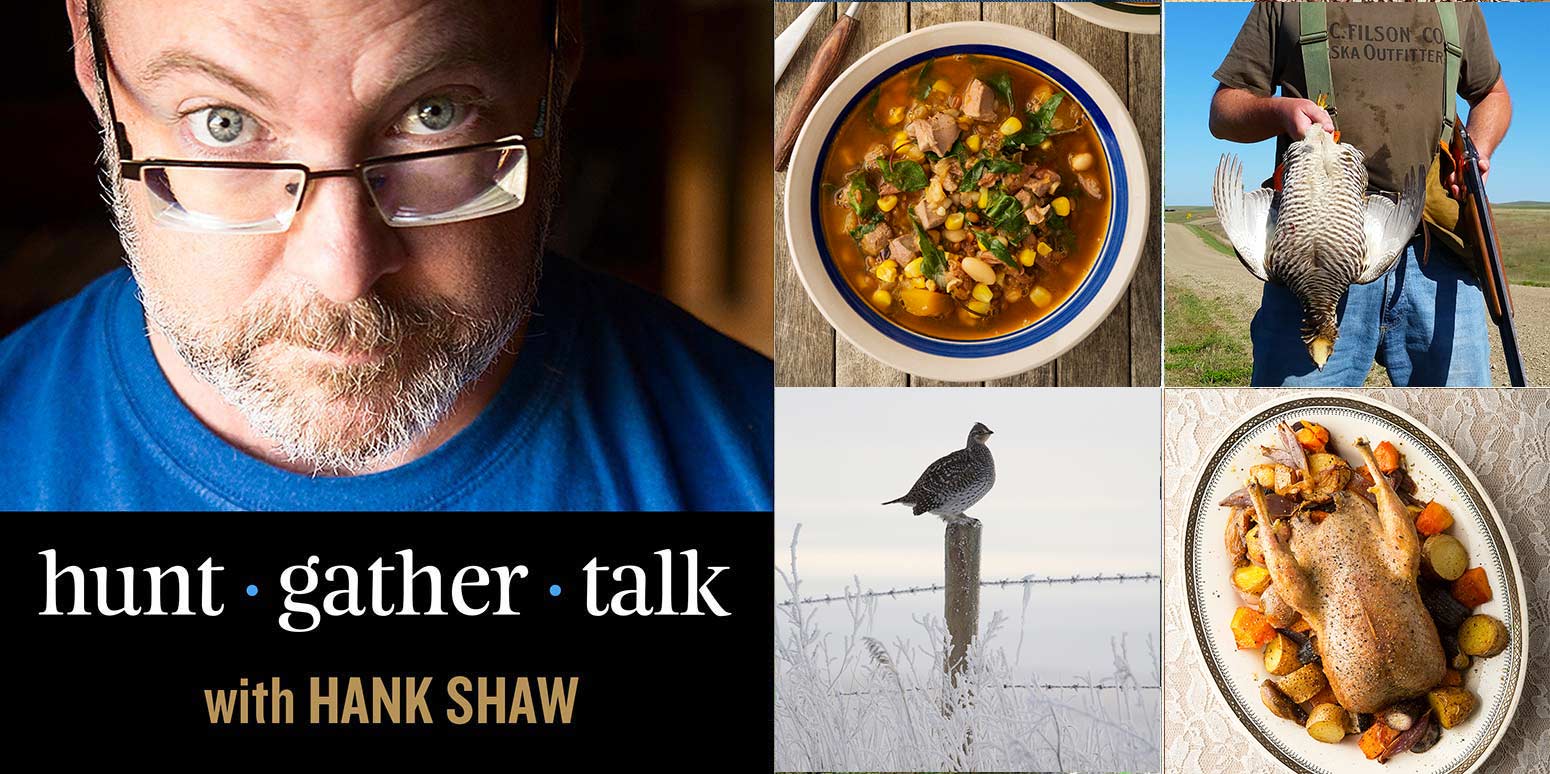

Welcome back the Hunt Gather Talk podcast, Season Two, sponsored by Hunt to Eat and Filson. This season will focus entirely on upland game — not only upland birds but also small game. Think of this as the podcast behind my latest cookbook, Pheasant, Quail, Cottontail, which covers all things upland.

Every episode will dig deep into the life, habits, hunting, lore, myth and of course prepping and cooking of a particular animal. Expect episodes on pheasants, rabbits, every species of quail, every species of grouse, wild turkeys, rails, woodcock, pigeons and doves, chukars and huns.

In this episode, I talk with Marilyn Vetter, a board member of Pheasants Forever and the North American Versatile Hunting Dog Association, and lifelong hunter, about the grouse of her home in the Great Plains — the prairie chicken and the sharp-tailed grouse.

Both of us love, love, love hunting these birds, which are symbols of the Great Plains.

For more information on these topics, here are some helpful links:

- Marilyn’s dog breeding operation, Sharp Shooter’s Kennel.

- If you hunt Great Plains grouse, consider joining the North American Grouse Partnership, which works to preserve and maintain habitat for these birds.

- Cool information about the biology of the prairie chicken, and the sharp-tailed grouse.

- More from me on hunting sharp-tailed grouse and prairie chickens.

- A recipe for roast prairie chicken or sharp-tailed grouse.

- A recipe for sharp-tailed grouse stew.

- A recipe for sharp-tailed grouse, prairie style.

A Request

I am bringing back Hunt Gather Talk with the hopes that your generosity can help keep it going season after season. Think of this like public radio, only with hunting and fishing and wild food and stuff. No, this won’t be a “pay-to-play” podcast, so you don’t necessarily have to chip in. But I am asking you to consider it. Every little bit helps to pay for editing, servers, and, frankly to keep the lights on here. Thanks in advance for whatever you can contribute!

Subscribe

You can find an archive of all my episodes here, and you can subscribe to the podcast here via RSS.

Subscribe via iTunes and Stitcher here.

Transcript

As a service to those with hearing issues, or for anyone who would rather read our conversation than hear it, here is the transcript of the show. Enjoy!

Hank Shaw:

Welcome, welcome, welcome to the Hunt Gather Talk Podcast. I am your host Hank Shaw and today’s episode we’re going to talk all about prairie grouse. That means the greater prairie chicken, the lesser prairie chicken it’s extinct relatives, as well as the ubiquitous sharp-tailed grouse that you can find almost anywhere there are no trees. My guest today is Marilyn Vetter. Marilyn Vetter is a lifelong resident of the Upper Great Plains, and she is a board member not only of the North American Versatile Hunting Dog Association, but also of Pheasants Forever.

She is a longtime bird hunter and she has a lot of insight to lend to us to learn all about these crazy birds of the Great Plains. I’d like to thank Hunt To Eat and Filson for sponsoring this podcast and away we go. Marilyn Vetter, welcome to the Hunt gather talk podcast. I am super stoked to have you on to talk about prairie chickens and the not so elusive sharp-tailed grouse. Welcome.

Marilyn Vetter:

Thank you. I’m super excited about it as well.

Hank Shaw:

So for people who don’t know who you are, I know you as a member of the board for Pheasants Forever, but I think you were any number of other hats and you’ve got a long history with hunting, don’t you?

Marilyn Vetter:

I do. I suppose I my history is common to the birds that we’re going to talk about today. I grew up a creature of the prairie in the Plains as well. I spent my childhood in North Dakota, growing up on a cattle ranch here and interestingly enough, I wasn’t a hunter as a child. My brothers were probably because of the generation I’m from. I was not included in their explorations, but I grew up watching these birds fly around our pastures. I guess I didn’t treat them maybe with as much reverence as I do now, but I did grow up in the Plains and have experiences acquired through my last 25, 30 years of hunting that I actually took up with my husband.

So when I met my husband, he was an avid hunter and was pretty adamant that he dragged me along and I would say drag me along, because in the beginning days, it was truly dragging me along because we didn’t have dogs then. The experience was much less exciting and rewarding at that time without dogs, but-

Hank Shaw:

It’s harder to hunt these birds without a dog. I’ve done it. I’ve done it without dogs several times but you’re right, it makes things a lot different.

Marilyn Vetter:

For me probably because I grew up a kid that was a huge dog enthusiast, being on a cattle ranch we always had dogs. So for me, even if I didn’t hit a bird, just being out with my dogs that has absolutely changed the experience for me. So that I guess leads me into the next part of my journey of why we probably ended up actually having this conversation was, as we got into dogs ourselves and I got involved in the North American Versatile Hunting Dogs Association, both as just a lay person that used the organization to learn how to train my own dog to be getting active in their publication, getting on their board and have been on their board now for the last 20 years.

Actually in my last month of service on that board, and then because of that connection, also got connected to Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever and have been on that board for about five years and have learned so much being involved with Pheasants and Quail forever about so many different things. I think people tend to think the organization is limited to the pheasant and quail, and of course they are because they would think that because of the name, but when I got involved with the organization to see how the biologists that are scattered throughout the country really help farmers and habitat enthusiasts with all kinds of bird populations, including the prairie birds we’re going to talk about today.

Hank Shaw:

I’m a life member of Quail Forever because I live in Northern California, and we only really have dozens to the degree that the Midwest does, but we have lots of quail. The habitat things that these groups do, and there’s a prairie grouse, North American Grouse Partnership and then the rough grouse people and the critter clubs in general. They are all about creating a habitat for not just the specific bird, but everything that lives in that particular environment.

I think I definitely want to spend some time talking about conservation with these prairie grouse because there’s a very different story between chickens and sharpies. The chicken population is not terrible compared to where it was a couple 20, 30 years ago. Sharpies are doing okay, but the limit of prairie chicken habitat is much much smaller than where sharp-tailed grouse live and there’s some reasons for that.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yeah, you’re right. There’s another link between a bird you just talked about, quail and these prairie birds in they both love fire and the ramifications of fire. So another interesting connection.

Hank Shaw:

So you run German shorthairs?

Marilyn Vetter:

I do.

Hank Shaw:

Your kennel’s the Sharp Shooter’s Kennel, isn’t it

Marilyn Vetter:

That is correct.

Hank Shaw:

So how did you get into doing, actually, I mean, everybody who hunts these grouse more or less if you live out there, you’ve got dogs but there’s a big difference between running dogs and owning your own kennel.

Marilyn Vetter:

There is and so for me it is still, I dare say it’s a hobby, a hobby that probably takes every second of my spare time outside of my real job. It is my husband’s full time job, of course, but there is a big difference. I think the connection Really though, in the end was we started out in German shorthairs and got our first dog out of the paper for $100 and she still holds a very, very special place in my heart and she was a fantastic dog. She really was.

I would tell you that she was a great meat dog, but what we saw through the time of going from a dog that was $100 to dogs that came from established breeders was our other dogs tended to be either healthier, they tended to have particularly much better structure so that they could last in the field all day long. When you talk about prairie birds, in particular, you really need dogs that can last, and one of the things and people that know me will probably roll their eyes because my husband and I talk about this all the time, is that if you have dogs with bad feet, you are not going to have a good prairie dog.

One of the things that we noticed on our very first dog was that she didn’t have great feet. She wasn’t bred to have good tight toes. She didn’t stand high on her toes. So when you run around the prairies, there’s cactus, there’s sandbars and just the sheer movement of going up and down hills that are covered in very tough cover and are built of sand will wear their pads off.

So if they don’t have good structure in their feet, they’ll be lame in a couple of hours. We’re blessed to have enough dogs that we rotate dogs and I would never propose that someone run one dog 10 hours a day for five days on end, but she would be spent in an hour and a half, two hours because her feet would be so beat up and you would have to rest her. So yes, we always we wore boots on her but even so it just was different.

Hank Shaw:

So can I interrupt for a second and say just how evil sand birds are. I discovered them for the first time a couple weeks ago in Oklahoma. Oh my God.

Marilyn Vetter:

They are evil. Then we would get like stick tights. We always come with stick dates-

Hank Shaw:

They’re so much goat heads.

Marilyn Vetter:

They are. They are really awful. That’s probably the other-

Hank Shaw:

I was crawling under the fence which you’re having in Oklahoma. I crawled underneath the barbed wire fence not really looking. Like hundreds of them. The points are like, I don’t know what they’re made of. It’s like genuine wood and it goes right deep as, oh, it’s the worst. I can’t even imagine walking around barefoot on them.

Marilyn Vetter:

So that’s one of the other reasons we went with shorthairs is that, because we spend most of our time hunting out of the prairies, at least they’re easier to get. I mean, they’re pretty easy to get out of a German shorthair as opposed to a Griffin or even some of the German wirehairs that have a softer or longer coat, or God forbid, a Retriever. It was non negotiable. I was like, if we’re going to have dogs, it has to be a low maintenance dog because I don’t want to have to groom and and cut and all that kind of stuff.

So every now and then we’ll have a client’s dog with, and I’ll never forget we had a poodle pointer that was-

Hank Shaw:

They’re kind of foofy, aren’t they?

Marilyn Vetter:

Yeah, they can be. Some of them have great coats, more wiry, and then there’s others that are-

Hank Shaw:

That’s true. There’s one in Arizona I hunt with, a slick coated poodle pointer named Shiloh and she’s an amazing quail dog down there.

Marilyn Vetter:

That’s great and we had one then it was a little furball and we got into a field that was just full of beggars lice in South Dakota and we sent a picture to the owner and said, so we either have to like sedate and try to get this out or we can shave her because it was awful. So for me those are the kind of telltale signs of that why we decided that we really wanted to put an emphasis in good breeding so that dogs have good coats, good feet, good structure, everything about it.

Obviously you want to breed for nose and desire and talent, but in German shorthairs, most dogs have a pretty decent, you can get by with a lot of them from a talent perspective if you aren’t a die hard hunter and if you don’t don’t care about water and because we are duck and goose hunters we also wanted to breed dogs that were enthusiastic, as enthusiastic about the water as they are about field.

Hank Shaw:

Thus the versatile hunting dog.

Marilyn Vetter:

Thus the versatile dog.

Hank Shaw:

It’s interesting. I don’t own a dog and I grew up with a with an Airedale terrier as a pet, but I’ve never owned a hunting dog and I travel so much so I feel it would be unfair to the dog. Owning gun dogs is a way of life. They’re much more than just a tool and you can’t just take them off the shelf when you need them. So I’ve never really felt justified to own one and I learned things like what you were just talking about. I would never have known about the feet or I could have guessed about the short coat because Shiloh the poodle pointer, she’s slick haired and she does really well in cholla and cactus down in Arizona.

Then I know, I’ve hunted sharp-tailed grouse with a much more of a, I don’t know, longer coated foofy kind of poodle pointer as well. My friend Jim Millensifer, who we did a show on ptarmigan and Himalayan snowcock, he runs a, dogs are much more fluffy I guess you would call it.

Marilyn Vetter:

Well you might be the smartest guy in the lot because you know lots of people that have hunting dogs and you don’t have to worry about all the rest of it.

Hank Shaw:

T’s the thing about boats too, right? It’s, you don’t want to own a boat. You want to know somebody who owns a boat.

Marilyn Vetter:

Which is why I no longer own a boat.

Hank Shaw:

Let’s take a step back for a second, and when do you first remember actually having a close encounter with either a prairie chicken or a sharp-tailed grouse? Doesn’t necessarily have to be hunting.

Marilyn Vetter:

Probably when I was, not probably, when I was a little kid. So when I was really stressed We had dairy cattle. We were of the Grade B type, for anybody that knows anything about dairy farming. So our cattle were free ranged, which meant that at twice a day my mom would do the early shift. She’d walk out and round up the cattle and bring them back to the barn for milking and sometimes in the afternoon, my sister and I would walk out and round them up and bring them back for milking.

Invariably, we would find a [inaudible 00:13:32] grouse. It was always really shocking, both literally and figuratively when you’d encounter them because particularly if they’re not hunted, they tend to hold super tight and they’ll scare the bejesus out of you when they get up right in front of you or right behind you. Those are my first experiences of like, what are these pesky birds doing with the cattle and even now when I’m hunting in the Fort Pierre area, it’s fascinating to me how much I see the birds travel with the cattle.

Hank Shaw:

It’s true. It’s true. I was doing some research on this and both birds they’re not obligates of bison but they’re linked with the bison for a couple of reasons. One, prairie chickens are tall grass prairie birds and they’re specific to that style of the Great Plains. There’s short grass and tall grass prairie but it’s not like they love too much of the tall grass prairie because it hides other predators but when the bison would run through and eat everything and create big footprints in mud and that would create little havens for green grass and for bugs, and they would get the grass shorter.

Then the big giant bison droppings which get bugs in them and all of these gallinaceous birds, all of the chicken like birds that we’re going to talk about in this whole podcast, let alone the little on this episode, they all love their bugs. I suspect and there’s been some science to this is that without cattle or bison, the both kinds of these prairie birds do not do as well.

Marilyn Vetter:

I would agree with you. In fact, when we were out in Fort Pierre a couple of months ago, we had a chance to talk to one of the local biologists and it was a wonderful education for me because he talked about how he, he as his job working with the local ranchers is they determine because the local ranchers rent those grasslands, those public lands, they determine which fields or which pastures will be grazed early, middle and late season and then they rotate that and he gave us a great tutorial on well, so just go watch.

If you watch, you’ll see like if you graze it early season, then those pastures are pretty good late season. That’s where you’re going to find your big adult birds, but if they raise them late in the year, there’s probably not going to be much there but you can bet that they might be pretty strong contenders the next year, because there’ll be birds and they’re going to graze it late in the season.

So it was really fascinating to see how he works with the local ranchers to make sure that they don’t over graze. A couple of years ago when we were there, there had been a terrible drought and they had to open all of the pastures to grazing and quite honestly, it was like walking around in a soccer field. It was just amazing. You had to walk literally five miles to get super deep into the cover where maybe other people hadn’t gone to actually find a bird, where this year because it was so wet out in the Dakotas and there was a lot more cover and it was interesting to see how the birds were much more dispersed.

Hank Shaw:

That’s interesting. It sounds like they’re controlling now for that succession where the birds follow the great herds of bison and now we’ve got cow. I was looking at some other things about habitat. So we’re going to talk about some habitat issues in terms of how to find these birds and hunt them in a minute, but both species hate trees. The sage grouse hate trees especially and they’re kind of known for that because trees, a few trees are okay for for a windbreak, but in general trees are where hawks live and hawks are their biggest enemy. Cedar is kind of the main culprit for all the prairie grouse. The Juniper in the West and cedar where you are, If you are listening to this and you’ve got land and you want to make it better for prairie grouse, get rid of most of your cedars.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yes. 100%-

Hank Shaw:

They hate power lines too.

Marilyn Vetter:

You bet. Wherever you’re going to see raptors, that’s where you want to try to get rid of as much as you can in your culture. It’s interesting. A couple of years ago, when we were out on the prairies, we ran into a farmer, a rancher, actually, and he stopped us and asked us how things were going and he asked where we were from, and we said, “We currently live in Wisconsin,” and he said, “Oh, you have a lot of trees there. So what do you think about this place out here?” He said with without any of the trees.

We said, “Well, we love it because we come out here to go hunting for prairie grouse.” He said, “Well, you know, trees just obstruct the view.” Native Americans did call these birds fire grouse, and so bison act, I guess like a walking version of fire in that when bison come through a field, they eat everything and which is why they’re really good for prairies and cattle tend to be a little more selective.

They look for the lush green grass and sometimes they leave the invasive species which can be even more problematic to pastures where bison almost act like a fire. A fire comes through and it wipes everything out, particularly cedars. So it’s how you keep seniors at bay. So fire is really important part for these birds to have sustainable habitat.

Hank Shaw:

So I’m familiar with the fire suppression problems that we’ve had over the last really 100 years in the West, where the theory was that you don’t let any fires happen and now we get these horrible ladder fires that can burn millions of acres. So it’s my impression that it’s been a similar philosophy in the Great Plains where they didn’t want any fires at all. So that you’ve got a lot of sort of gunk in the places that are not actually farms and I don’t get the sense that they do any control burns there or if they do, maybe they’re just starting them. Do you know anything about this?

Marilyn Vetter:

No, you are correct, unfortunately for the birds anyway that there hasn’t been and obviously I understand, I grew up on a cattle ranch and it’s important for the two systems to work together. Also growing up on a cattle ranch, I saw how uncontrolled sage completely took over our pastures. People were taught, particularly early on my father was a depression era child and so they feared fire and they were taught to avoid it at all costs.

They used a number of herbicides to try to control the sage and it never really worked. It just never really worked. One wonder sometimes if fire wouldn’t have been a better suppressant for that sage because, while he wanted to have grass roots pastures, it really took over. Maybe with time and further study, but I see it now when we go out to the prairies or even when we’re just popping around the pastures here in North Dakota, if without some level of either grazing or fire, you see all of those bushes and shrubby species, like any kind of conifer come in, and they take over pretty quickly.

Hank Shaw:

That’s interesting. I know Quail Forever in the south is doing controlled burns all over the place and I’d be interested to see if any of the other organizations are going to get into controlled burns and well, maybe in places like the Fort Pierre grasslands or if it’s, and this is actually kind of another issue that we should deal with in terms of where do you get to these birds. Prairie grass live on private ground, and so it’s private ranchers and private landowners in general, who have much of the conservation burden, and opportunity and since, I remember, I hunted I don’t even remember what the town was near but it is in South Central western North Dakota.

It was an amazing series of ranches and private ground and it was right on the other side of the river. There’s chickens everywhere, but it was managed for that because the private landowner, he did guided hunts. So if you wanted to get on chickens, he had been actively managing for that and if you are listening to this and you want to go and hunt prairie chickens, how would you suggest someone go about it?

Marilyn Vetter:

So we spend most of our time now on the grasslands in South Dakota, which are all obviously public, and we do some of it back here in North Dakota on private land. It’s a little harder than it used to be because of the lack of CRP and that program which is not necessarily great for grouse, don’t get me wrong but because of that lack of sign up, a lot of land has been tilled that wasn’t necessarily tilled previously.

Because farming techniques have changed a lot and because of no see tilling and without, I mean no till seeding, a lot of land that didn’t normally get planted, let’s say four years ago can be tilled and planted today because it actually can sustain a crop. It doesn’t have to be plowed and exposed to erosion and all kinds of other things. So there isn’t necessarily as much cover as there used to be when I first started hunting 30 years ago.

We went around the hills in the Butte, North Dakota area or in the Wing area of North Dakota. It’s funny you said the town you can’t remember the name of because most of the little towns are 20, 30, 40, 100 people and they’re hard to remember the towns until you’ve been there but there were pockets that were very hilly, and there were pasture. Quite honestly, those folks are the salt of the earth. You stop in yards and you ask if you can hunt and nine times out of 10, as long as it’s not deer season, they’re pretty great about it.

When it comes to deer season, they want to have that land undisturbed and they might even say a week before deer season, we don’t want anybody walking in there to scare all the bucks out. Those are obviously what I tell you is I go to the local coffee shop in the morning in any one of those little towns and that’s where you’re going to run into ranchers, that offseason or maybe not out making hay or hauling hay and you might be able to catch them in the morning to see if there’s a good place in the area or even on their place.

Generally, if you can act like a respectful person and be knowledgeable about the fact that hey, I’ll make sure I close every gate behind me whether there’s cash They’re not in thank them for what they do, most of the time, they’re pretty cool about it. If you don’t necessarily want to try that, I’d say strap on your hiking boots and go to the the grasslands out in Fort Pierre. It gets a lot of pressure. So you’re going to see birds pretty dispersed and you might have to put on more miles, but it’s a humbling experience and it’ll certainly teach you a lot.

Hank Shaw:

What about the public walk in program? It’s kind of legendary in both of the Dakotas as far as, yeah it’s private ground, but it’s part of a program where you can walk in. Some places make you sign in, and some places, I think in North Dakota that unless it’s posted, you can hunt it.

Marilyn Vetter:

That’s correct. The PLOTS land and in fact, so my husband and I both grew up around the Harvey, North Dakota area and actually where I’m sitting right now is on the family farm and we’re surrounded by a lot of either PLOTS land or waterfall production here. In those areas you can, you’re right if they’re not posted because they are owned by private citizens, if they’re not posted you can definitely use that cover.

What I have found, now some of that is great, particularly if it’s hay land. So there’s a particular stretch about three miles from where I’m sitting that every year they make hay out of it and that’s a great place for us to find grouse. A lot of the other PLOTS land might have a little more brushiness to the edges, it tends to be more pheasant country. One thing I’ve, this was actually doing a little research I learned that I wondered why you don’t see pheasants and grouse together more than you do. Part of it obviously they’re in like different habitat but one of the things I read was that pheasants will steal a nest from a grouse.

Hank Shaw:

I read this too. This is awesome.

Marilyn Vetter:

Isn’t it strange? So then the chicks hatch First, the pheasant chicks hatch first. The grouse typically, not abandons but they don’t spend a lot of time with their chicks. Those chicks are pretty independent very quickly and when they see that the chicks have hatched they leave the nest and the grouse eggs have are then for all intents and purposes abandoned, and then they don’t hatch.

Hank Shaw:

You know what’s crazy? There’s another famous game bird that does that. It’s the redhead. The redheaded duck is a, there’s a classic ornithologist term for that. It’s like nest surrogate or whatever and the cuckoo is the most famous one. It’s a thing, like there’s a whole bunch of birds that do that and just like you I just learned that the disco chicken’s stealing our grouse.

Marilyn Vetter:

I guess that’s what happens when you bring in a non native bird. They have to make do what they can.

Hank Shaw:

That’s true, but we can flip it over in that sense that both sharpies in prairie chickens can snow nest where pheasants cannot. So I’ve seen it, I know you’ve seen it where it’s, you get a big old blizzard somewhere in the Great Plains, and it’s just cold. It’s just super cold, like cold, like Canadian cold. Pheasants need a lot of cover to not die in that because they’re from China. They’re not from a super cool part of the world and both of them are prairie grouse along with Hans by the way. Hans are the only non native gamebird that we brought here that can also dip under the snow and make a little burrow and yeah, it’s still cold but it’s 32 under the snow, not negative 40

Marilyn Vetter:

Yeah, they find a way to thermo regulate in it. It’s fascinating, a cold December or early January last couple of days of the season, you can be driving around and you’ll see sharp tails sitting in a tree and they’ll be covered up but they’re roosting on it and they’re trying to soak up the sun or on those sunny mornings, where pheasants they they typically don’t necessarily do that. You can tell that they haven’t necessarily fully adapted.

When you have terrible snowstorms and what do pheasants do? They go to that heavy, heavy cover and I’ll give you a great example happened here about six weeks ago when North Dakota, at least this little pocket of North Dakota, got slammed is 30 inches of snow in the middle of October. What happened is the pheasants went to that tall cover and a lot of them didn’t survive it because the cattails weren’t dry enough yet. If you drive around in the [slooze 00:30:01] right now a lot of them are just flat and we had a lot of locals tell us that when they went out early season and walk around, they find a lot of dead birds because they, I’m sure, suffocated.

Hank Shaw:

Wow. We’re going to do a whole episode about pheasants with some Pheasants Forever guys because there’s a whole, like it’s a thing. It’s a huge deal, A to chase and especially in South Dakota, but it’s also this strange management of a bird that, you’re right, hasn’t fully adapted. Actually, I’ll tell you where Bezos would be amazing and if we changed our farming practice where they’d all be, California.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yeah, they’d do great there.

Hank Shaw:

Because you’re never going to get a 30 inch snow in the Central Valley of California.

Marilyn Vetter:

If you do, we have other things that we would be talking about.

Hank Shaw:

Run, please. Armageddon.

Marilyn Vetter:

One of the other things that you asked about is how you find these birds. One of the things and this year was really evident. So the first time we went out to the grasslands, we jumped out of the truck, the very first field and the first thing that happened was hundreds of grasshoppers popped up and we looked at each other and like, this is going to rock, this is going to be amazing and it was incredible. There were a lot of birds in those areas where we found, as you said, insects and early season they like, early after nesting they like a very different bird., but boy when it comes September, October, that what’s puts their body fat on for the winter is grasshoppers.

Their crops were just slammed with them. So that’s the one thing I always tell people is if you’re lucky enough to shoot one, the first thing I always tell you is open the crop and that’ll tell you what they’re feeding on and generally that bird’s not alone in its idea, every one around them. So when you look for other fields that look contiguous, or at least similar to that, you’re going to find what they’re eating.

When we went back six weeks later, they’d already had a frost, things had changed dramatically and when we went to the same areas, there were hardly any birds around, but there was still a lot of standing crop. Particularly, sunflowers hadn’t been taken off yet. So when we started looking for the grasslands that were bordering sunflower fields, that was where A, we found larger cubbies, and they were bordering those crops that hadn’t been harvested yet.

Hank Shaw:

Sunflowers are a great one and I don’t think I have ever actually killed a sharp-tailed grouse in the Great Plains where there were not rose hips.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yes, absolutely. Buffalo berries are another one too, but they do like rose hips.

Hank Shaw:

Which is cool because, the first time I ever came, I got to tell you about the first time I ever hunted sharpies. So the first time I ever hunted sharp-tailed grouse, I got the opportunity to do it with my friend Chris Niskanen, who is a Minnesotan, who got me into hunting many years ago. We got the opportunity to hunt a ranch in eastern North Dakota, that had never been broken by the plow. Ever.

Marilyn Vetter:

Wow.

Hank Shaw:

It’s an amazing place to be with and just like you said it was rolling. It was very diverse flora. Tons of mushrooms, tons of rose hips. See, I’m a forager. So I’m always looking for the edible things, but there’s just no monocultural at all. It was just chip shot hunting. You had to walk but the one thing I found all the time is, we never found them in the flats. I started to name them the other side of the rise grouse because you would walk up this rise and you pretty sure there’s probably going to be some grouse on the other side of the top of that rise.

So you hold yourself and catch your breath before you get to that top because as soon as your head breaks the plane to the top, those birds are going to fly and you got to whack them as they’re flying away. Every single time, every time they would just be on the other side and I think what happens is they’re on the top when you’re climbing up and they hear something but they don’t necessarily know it’s you and they’re like not so sure about this.

Sp they kind of inch away and inch away and inch away and when they see the big hairless ape with a bang stick, they go, oh my God and fly away and then you get your chance to get at them but it was ridiculous, Marilyn. It was ridiculous.

Marilyn Vetter:

It’s so funny that you say that. This describes exactly, so were out just a few weeks ago in South Dakota and it was the exact same thing and it was like, we were laughing about that you have to save, you’re sprinting for the last 30 yards up the hill because you got to get up there as quick as you can. Because as soon as they see you, they’re going to take off.

Hank Shaw:

I was talking to another North Dakota named Tyler Webster about Hungarian Partridge. One of the strategies you do for Huns is you can see where they flush and then you can go chase them. I don’t think I’ve ever been able to reacquire a covey of sharp-tailed grouse.

Marilyn Vetter:

No, no, I haven’t either. Like sometimes the very first weekend. If you get into a young hatch, you might be able to break them up a little bit or you might have a couple of stragglers that don’t break cover with the rest of the flock. You’re right, you can pretend that you’re going to chase them down all day long. That doesn’t happen. You might get a couple of singles, but you won’t get the whole covey.

Hank Shaw:

It’s nuts. The first time I ever flushed a flock, which was very early in my hunting career, which is 18 years ago now, because I started hunting as an adult too. Niskanen and I flushed these sharpies and it was like, up gone. They’re in North Dakota now. He’s like, sorry, you’re never going to see them again. They’re now out of your life.

Marilyn Vetter:

They laugh at you as they go.

Hank Shaw:

They do, they do. It’s like, the chickens are quieter.

Marilyn Vetter:

They are. They are a little bit more deceiving. I think sharp-tailed are easier to, actually when I think about sometimes when we’ve taken novices out. One of the things that’s the hardest for people to distinguish is a hen pheasant. If you aren’t a super experienced hunter, you don’t think about look at the tail and look at the shape of the tail and the length and I always say if they’re laughing at you as they go, it’s a safe shot. You look for the white feet on sharp-tailed, but chickens can be a little harder. They’re smarter, they’re quieter.

Hank Shaw:

They’re much more quieter, but you can re-acquire them. I have re-acquired chickens. I’ve never re-acquired sharpies. Have you ever pass shot chickens?

Marilyn Vetter:

I have not, I have not.

Hank Shaw:

So it’s a thing. Chickens are way more habitual than sharpies are. So if you have an area that has a lot of prairie chickens, especially a little farther south, they will do their thing during the day and they’re like turkeys in a sense where there’s a spot that they all want to sort of meet up and spend the night. So quite often they will fly over a spot to do that. You’ll see, unlike most grouse, you see them flying around, which is pretty unusual because they’re walking birds.

So you can set up against this fence line or in some corner and wait for these guys to fly over right before dusk and you can get into them in that and I’ve done it not terribly successfully, but the day after I tried it on this cornfield in North Dakota, the guys who did it, they all limited out.

Marilyn Vetter:

Fascinating. I did not know that. I will have to look for a place where I can do that. That would be fun. It’s almost like pass shooting ducks.

Hank Shaw:

It is exactly like pass shooting ducks except they’re a lot slower.

Marilyn Vetter:

Thank goodness. I’m less successful at pass shooting on ducks.

Hank Shaw:

I had public [inaudible 00:38:25] in California. So whenever I have the opportunity to hunt fancy clubs, where the members are all used to feet down in the decoys and we’ll come back from a duck hunt and Holly and I will be absolutely loaded down with like ducks and geese and snipe, you name it. It’s like everything was there and we managed to kill it, because we’re good pass shooters and they’re just not, I find that people at the fancy clubs are not as good as a 50 yard streaking duck.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yeah, because they tend to be shooting put and take birds that get up 20 feet in front of them and they fly straight away.

Hank Shaw:

No, that’s with persons but with ducks. They’re used to like the birds feet down in the decoys and then they’ll shoot them.

Marilyn Vetter:

Take a couple of decoys with them at the same time.

Hank Shaw:

I’ve seen that. I saw a guy absolutely mangle like $100 full body flocked goose decoy. It was like, nice. You’re buying lunch dude.

Marilyn Vetter:

Exactly.

Hank Shaw:

Hey, I’d like to take a moment to say that Hunt To Eat is a proud sponsor of this podcast, which makes sense because I own and wear a lot of their shirts, hats and other gear. When you reach into your drawer to grab a shirt to wear to a barbecue or a conservation event, you always grab the same one, right? Well, you’re about to find your new favorite tee. Head over to hunttoeat.com and check out their line of hunting and fishing lifestyle hats, hoodies, tees and more. They’re super soft. They’re a great fit and they’re designed and printed in Denver, Colorado.

Be sure to check out the new line of Hunter Angler Gardener Cook apparel, and use the promo code Hank10 for 10% off your first order. That’s Hank10, H-A-N-K10 and you get 10% off any Hunter Angler Gardener Cook merchandise you feel like picking up and wearing to your next event. Thanks. So let’s talk about gear for a second. It’s my impression that other than, I wear a pair of Filson chaps which I like a lot and a jacket and water for your dog and a light gun.

I shoot a 20 gauge over and under that weighs only about five and a half pounds. I call her Tinkerbell. That’s about all you need for this. This is kind of a cool low equipment hunt in my experience.

Marilyn Vetter:

So the other thing that’s nice about it is because you can, for us that are dog owners, you can see your dogs, you don’t have to wear bells on them. You don’t have to wear beeper collars on them which is probably why they are my favorite bird to hunt because it’s quiet. The only thing that I would add to that for dog owners is I think dog boots are a must. It’s just so that’s you have your dogs for the five to seven days that you’re out there you want to make sure that you keep their feet pretty good. We, because we are dog owners, we carry a first aid kit with our dogs on us all the time.

Hank Shaw:

Porcupines, endless porcupines.

Marilyn Vetter:

That’s definitely one of them. I think the other thing is depending on where you hunt, there are, particularly early season or early to middle season, there’s snakes. So we through, this was actually a kind of a tough season out in the prairies in Fort Pierre. There was a lot of snakes around this year and not that we saw a lot of them but we heard a lot of stories about dogs get getting struck. So for the first time we did vaccinate our dogs, which we know it’s not a sure thing, but it increases your odds to get them to the vet in time and hopefully increases their survivability.

As we were leaving the vet one day when we think our dog was probably got a glancing shot from a snake. As we were leaving the clinic, somebody was bringing a dog in in his arms and that dog unfortunately did not make it. So, for anybody that is hunting prairie grouse, anywhere that there are snakes present, I always recommend, now, I recommend that you should vaccinate your dogs ahead of time if you can.

Like I said, it’s not a sure thing, but it greatly increases their chances of survival, but yeah, good hiking boots. They have great traction and I think that Filsons are probably at least a little bit better for snake proofing you as a human to and the other key thing for people that have dogs and actually just for yourself is avoid prairie dog towns. Do not hunt anywhere near them because that’s where snakes live.

Hank Shaw:

I guess it makes sense because they like to eat prairie dogs.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yes. We want them to live there and eat as many prairie dogs as possible because they’re hard on cattle, they’re hard on land, they’re hard in humans with the holes that they create and they really destroy a ton of property.

Hank Shaw:

I got a great prairie dog story. So I’m in eastern Montana near Miles city. It’s like the second year ever hunted and friend Tim Huber decided that he wanted to shoot the world’s largest mule deer doe, like five miles from the truck.

Marilyn Vetter:

Smart going.

Hank Shaw:

I didn’t know any better, right? So he shoots the world’s largest mule deer doe. It’s like a 200 pound mule deer doe, it’s huge. I mean, lightweight. So, again remember, I’m brand new Hunter. So Tim says, all right, now we got to drag it out. Drag it out? That seems like a long way to drag a deer. He’s like nope, we’re going to drag it out. Oh, okay. So it was one of those deers where you tie ropes around your wrists and through the achilles tendons of the deer because yours no human can have a grip for that long with that much weight.

So we’re doing this sort of Bataan Death March back to the truck and we get through a prairie dog town. So Tim told me that the ranch owner was like, yeah, you shoot as many prairie dogs you want. I’m like, why would anybody want to shoot a prairie dog? I learned because we’re dragging this dead deer through this prairie dog town and the prairie dogs are like, constantly. Constantly yelling at us. It took us like a good 20 minutes to get through this prairie dog town. So at one point, I’m not proud to admit it, but at one point, I stopped dragging the deer, racked the shell and just started blazing away.

Marilyn Vetter:

It had to feel very rewarding, like, stop laughing at me.

Hank Shaw:

I might have killed one and then I stopped and I realized this is not a good idea. Then we just put our heads down all of them yelling at us the whole way. There was like no fur on the deer when we got it back and it was not our finest hour.

Marilyn Vetter:

[inaudible 00:45:35] that’s for sure. In fact, you are right, every cattle rancher will say, shoot as many as you can, and primarily for those two reasons. It destroys their pastures and it causes cattle to fall in holes and break their legs or their horses when they’re out rounding up cattle. So they are really destructive little critters and in fact, there are many opportunities. If it’s a 95 degree day, early season, that’s the perfect opportunity to stop from noon to four, and start planking around with if you have a long barrel gun to plank around with those prairie dogs. Actually there’s a fair number of people that they go out there just for that to just shoot with long barrel guns to, they’re great target practice for them.

Hank Shaw:

I’ve heard about that too. They do that with ground squirrels out here in the West.

Marilyn Vetter:

Interesting.

Hank Shaw:

The weirdest thing about ground squirrels and I don’t know if the prairie dogs do this. If you shoot one ground squirrel, his brother Louis, will come up and start eating him. Like I never liked you anyway.

Marilyn Vetter:

They are non discriminate about, I don’t think they have a very good emotional tie to each other. They’re the same way.

Hank Shaw:

I was horrified. I was like, oh my God, he just Louis.

Marilyn Vetter:

You’re dead, you’re food.

Hank Shaw:

So have you ever chased any of the other, so mostly we’re talking about the common sharp-tailed grouse and the greater prairie chicken but there are other chickens. There’s the Attwater’s prairie chicken, which has a remnant population in Texas and I don’t believe anybody alive has been able to hunt the Attwater’s. There was a fourth called the heath hen, which is an Eastern prairie chicken.

The heath hen is the reason why the greater and lesser prairie chicken were so heavily really market hunted in the 1800s and early 1900s is because when the colonists arrived on the east coast in the 1600s, there was a prairie chicken there called the heath hen, which basically looked more or less like a lesser prairie chicken, and it would be in every meadow and grassy area east of the Appalachians.

Well, the last one died and I believe 1932 on Nantucket island of all places. So there was this bird that was in common consciousness as a game bird and a food item. So when American society ate up and destroyed the habitat of the heath hen, and then after that they Attwater’s, then what was left was the lesser and the greater.

So, I think we mentioned before we went on the air was there used to be millions and millions and millions of prairie chickens and especially in places like Illinois, where there’s a museum population of them now. There’ one like 2,000 acre experimental spot for them to live and they live. They’re okay, but it’s not like they’re going to get any extra habitat anytime soon.

The last place in America that you could hunt lessers was Kansas and they closed that in 2014, alas, before I had a chance to hunt it. So I will never probably get the chance to hunt a lesser and for sharp-tailed grouse, there are lots and lots and lots of different sharp-tailed grouse. There’s many, many subspecies and I’ve hunted one other one, which is the Columbian sharp-tailed grouse.

It’s in kind of western Colorado of all places, and it’s pretty difficult sharpie to chase but there’s different subspecies all the way up to the Yukon. I’m wondering if you’ve ever chased any of these more unusual sub variants of what we’re talking about?

Marilyn Vetter:

I haven’t. I think I’ve been spoiled by having access to and maybe just get into a rut, and I haven’t. I have not hunted any of the other grouse.

Hank Shaw:

I think what we need to do is plan a trip to Alberta, because Alberta has another subspecies of sharp-tailed grouse, that its feathers are a little different from the ones that you find in the Dakotas and in Kansas and Nebraska. I have friends in Alberta, so we should do that.

Marilyn Vetter:

I love that idea because I also have a boatload of cousins in Calgary.

Hank Shaw:

Oh, there you go.

Marilyn Vetter:

I think that sounds like a perfect trip.

Hank Shaw:

Calgary, Dallas of the north.

Marilyn Vetter:

Of the far north.

Hank Shaw:

Well, not far north. Most of my friends are in Edmonton and they’re like Calgary. It’s so hot down there.

Marilyn Vetter:

Well, my father grew up and was born in Saskatchewan. So they migrated from Saskatchewan to Calgary. I guess they decided they want a little more culture.

Hank Shaw:

Well, it’s an actual city. How big is, even is Regina or Moose Jaw, those are the two big towns in Saskatchewan. I don’t think either of them have more than 100,000 people in them.

Marilyn Vetter:

I would bet they’re not even, I really don’t know. It’s been a long time since I was there. That was exactly the area where my father was born was in that Regina Moose Jaw area and where most of my cousins lived in their early years till they moved to Alberta. It looks very, very strikingly like North Dakota, that you don’t see big population centers.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, that’s true. Manitoba is kind of like that outside of Winnipeg.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yeah, exactly. It’s interesting. The hunting culture is really not as strong just north of the border in Canada. I have a lot of friends that have hunted sharp-tailed in Saskatchewan for most of their lives and they say when they go up there, the only other hunters they encounter, Americans.

Hank Shaw:

It’s pretty true. I mean, I know a bunch of hunters in Alberta, and that’s about it but I have duck hunted in Manitoba and again, it’s mostly Americans. We were on the duck hunt in St. Ambrose and I was like, “Oh, man, that looks like a really good spot to hunt rough grouse.” The guy was like, “You mean chickens?” Like, yeah.

Marilyn Vetter:

Knock yourself out.

Hank Shaw:

Yes, exactly. It was like, you want to hunt them? I’m like, absolutely, I do, and man. Have you ever hunted rough grouse in the West?

Marilyn Vetter:

I have not. I’ve only done it in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

Hank Shaw:

Well, see you’ve hunted real rough grouse, like actual gamebird rough grouse, which I love it to death. It’s one of my favorite things to do. However, if you ever get yourself into rough grouse territory, apparently in Manitoba and also in kind of the Rockies area, I don’t know there’s somehow developmentally disabled. They’re just not smart birds.

Marilyn Vetter:

Perfect for me.

Hank Shaw:

They’re just not smart birds. Sometimes it’s like, well, I got to eat. So they’re not quite as dim as spruce grouse, but they’re close.

Marilyn Vetter:

Spruce grouse are pretty dim. Yes, they are.

Hank Shaw:

Poor birds.

Marilyn Vetter:

Thankfully they live in an area that it’s hard for any lazy person to get to. So that’s probably why they aren’t extinct

Hank Shaw:

We’ve had very, very strict bag limits on them. Just be nice to them forever too.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yes, it makes sense that we take care of the needy ones.

Hank Shaw:

How would you describe the difference in personalities between the two birds, sharpies versus chickens?

Marilyn Vetter:

Oh, that’s an interesting question. I find the chickens to be, I’d say almost a little smarter sometimes because they’ll let you sometimes walk right past them. Maybe they’re more courageous. They’ll hold tight, where sharp tails will always, always break free of the cover. They know you’re coming, and they won’t take the chance that you might walk right by them.

So obviously having dogs helps a lot because if your dogs are generally anywhere in the area, they’re going to smell them. We had a couple happen this year where the dog had gone around the bottom side of the hill come up the top, come up from the other side, which they learned to do because they know the birds are going to break. It was fascinating because it was actually chickens that we were working and not sharp-tailed.

So the dogs are thinking, well, these are sharp-tailed, they’re going to flush, right? Well what happened is the chickens held because I was the one that had walked past them, not the dogs and they got up behind us.

Hank Shaw:

Did you manage the pirouette shot?

Marilyn Vetter:

Well, I would have had to take the chance of probably shooting another human. So I did not.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, but chicken is worth it.

Marilyn Vetter:

I suppose who the human is, but no, I did not manage that. I was fascinated to see how much tighter they held. It was a really interesting season. I also, I think sharp-tailed tend to be more social I guess is what I would call. They tend to have bigger cubbies, particularly at the end of the season. It’s amazing how big their cubbies can get.

Hank Shaw:

I have noticed that too. I’ve noticed also that snipe are very similar to chickens in the sense that there can be a bunch of them in a given area, but they’re not in a blob, like Hans or quail are. So they could be two here, one there, four there and they may all get up within a couple seconds of each other but they’re not tight in a ball as much as I see sharpies are.

Marilyn Vetter:

Really very much so. I saw that more this year than ever, maybe because we saw a healthier population of chickens, where sharp-tailed when they get up, they do. They all fly together. It’s almost like they think there’s safety in numbers, and where chickens, it’s probably in the end smarter because there’ll be scattered everywhere and it’s almost distracting, and you only usually get one shot because they’re in such vastly different directions.

Hank Shaw:

Yes. Yeah, which it’s an interesting one because as a Western quail hunter, I’m trained to not necessarily shoot the cubby rise, because Western quail don’t all rise at once. So your trick is, I mean, a really good quail hunter which I’m not quite there yet, will go boom, boom and kill two on the cubby rise, quick reload your side by side over or under or whatever, whatever it is that you’re using, reload super fast. Because chances are you’re going to get one or two or even three chances at more birds that are stragglers.

Marilyn Vetter:

Exactly. That was when we hunted quail in Texas one time that it was exactly what I found out too is, they’re not all gone and actually, the smart ones are still there.

Hank Shaw:

I think usually the lead rooster or drake or cock or whatever the hell you want to call it, the lead male is one of the last to leave.

Marilyn Vetter:

I would agree.

Hank Shaw:

Hey, everyone, I’d like to take some time to thank Filson, the original Alaska outfitter for sponsoring the Hunt Gather Talk podcast. As you may know, I am rarely out chasing upland birds without my Filson jacket and tin cloth chaps. You should know that Filson was founded in Seattle, Washington in 1897 when they started outfitting prospectors for the Klondike Gold Rush, and ever since then they’ve been committed to creating the best in class gear for the world’s toughest people in the most unforgiving conditions.

Right now is Filson’s winter sale and you can save at least 35% on unfailing goods including classic bags, outerwear, boots, and more. This sale only happens twice a year, so be sure to check it out before the end of January. Let’s switch to, okay, we’ve got some birds in hand. How do you like to work with them in the kitchen?

Marilyn Vetter:

So I have two different methods that are my go to. So I think of sharp-tailed or prairie grouse in general as a little bit like cooking venison. They respond best to being cooked either in high heat, and I like them either rare or medium rare. I like them on the grill a lot with not a lot of adulteration to them, or I like to slow roast them in the oven.

Those are really kind of my methods. Maybe I’m also a creature of habit. It was interesting that you were talking about when you were hunting those birds in eastern North Dakota on that native land, and you said that you found them with a lot of mushrooms. When I think about grouse, particularly the prairie grouse, because they’re such a dark meat, thankfully, they don’t have that livery flavor and texture that you find in some birds.

I think that the best thing that you can serve with them is two things. It’s either mushrooms, which really enhances that really earthy flavor or you go to the kind of the alternative route, which is like apples and apple cider vinegar or sweet potatoes or those kinds of more, that sweet savory kind of combination. I keep it pretty simple. I guess I think about, I cook grouse kind of like how they are. I keep it pretty simple.

Hank Shaw:

How about plucking? Do you ever pluck your grouse?

Marilyn Vetter:

Chickens more so than sharp-tailed just because there’s just not a lot on a leg on a sharp-tailed grouse and chickens obviously are bigger birds. Their their skin is pretty fragile, tears really quickly. It’s not like a duck, or goose, where they have this really tough skin that you can, in fact, they’re super easy to fly out if you want to just take the breast because the skin tears pretty quickly.

Hank Shaw:

We don’t do that on this podcast.

Marilyn Vetter:

No, no, I know that. Chickens I think, or actually so I grew up on a farm where we cleaned 400 chickens a year. So, boy, I know how to pluck a bird. Chickens actually pluck like a chicken, like a standard old chicken in my mind. They’re pretty easy to pluck.

Hank Shaw:

The first time I ever plucked a sharpie was on that ranch, the unbroken by the plow ranch and that was before I learned that the best time to pick any chicken like bird is two to three days after it was killed. When a bird is no longer warm, but it’s still that same day or the morning after, the feathers stick way, way tighter than they will stick if you’ve killed the bird for two three days. This is especially true with sharpies.

Marilyn Vetter:

Especially true with sharpies. Not that I can say that I necessarily follow that technique, but I always let my bird sit all day long for sure till they cool down. The worst thing you could do is try to do it on a warm bird.

Hank Shaw:

Well, I don’t know. If it’s a freshly killed bird, it actually comes off quite easily, but it’s an hour later. Once that bird goes into rigor is your problem.

Marilyn Vetter:

Right. I guess I haven’t necessarily done one right afterwards. I suppose that makes sense when you think about that’s what we did on the farm with chickens, is you cut their head off and you did it right then. So they were pretty easy.

Hank Shaw:

So the only time I’ve ever done it is with the last bird of the day and I’ll be honest. I mostly just did it, to see how it would be, as an experiment.

Marilyn Vetter:

Good to know. I’ll have to check it out. I suppose you could do it right away, especially since they’re not that big, they don’t take that long to do.

Hank Shaw:

No. Here’s a fun, weird, bizarre phenomenon that I have noticed and other people I’ve talked to have noticed this as well. If you pick a prairie chicken and roast it, the meat is pink. If you take the breast meat off a prairie chicken and cook it, the meat is dark red. I have no idea why that happens.

Marilyn Vetter:

You are right.

Hank Shaw:

It’s the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen.

Marilyn Vetter:

I don’t know why that is either. There must be some kind of a protective or else a fat layer that’s between that skin and that tissue. I don’t know, but you are right. I have noticed the same thing.

Hank Shaw:

That’s so weird. It’s got to be chemical. It has to be something to do with the bones and, it has to be the contact with the phone that while it’s being cooked that does that because a roast prairie chicken and I’ll put a picture and the recipe for the way I do prairie chickens on the show notes for this. It’s unbelievable. It’s one of the reasons why prairie chickens and not sharp-tailed grouse were the dominant market bird 100 some odd years ago is because you could roast your prairie chicken and it’s not a chicken, chicken but it’s closer to a chicken, chicken than a sharpie would be in the sense that it’s kind of pink colored and not dark red. Have you noticed that the legs and the wings on sharpies and chickens are light meat?

Marilyn Vetter:

Yes.

Hank Shaw:

Super weird.

Marilyn Vetter:

They’re the opposite of everything else you encounter. I’d imagine that’s because they don’t really, I don’t know. I think it’s really, really odd. They are the opposite of what you find in every other species.

Hank Shaw:

Yep. So grouse are the same way and the only other bird I’m aware of that is like that is a woodcock.

Marilyn Vetter:

I didn’t know that about woodcock. Interesting. I’m sure someone could call and tell us what the rationale is for that, that knows more about it than we do.

Hank Shaw:

So here’s what I’ve been able to suss out. All of these birds do not run, they’re not runners. So pheasants are runners. The biggest issue with shooting a pheasant is making sure it’s actually dead because otherwise you go on a wild chicken chase. Whereas pretty much if you think poorly about sharp-tailed grouse, they die.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yes. They are fragile that way.

Hank Shaw:

Roughies are the same way. It’s not to say that I’ve never had runners, but it’s pretty rare to have a runner prairie grouse when you’ve hit it.

Marilyn Vetter:

Yeah, they hunker down.

Hank Shaw:

Do you use, just a little side note, before we go back to cooking [inaudible 01:04:20]. Do you use, I tend to shoot them with either lead sixes or I actually like bismuth fives too.

Marilyn Vetter:

I haven’t used bismuth, but I’ve actually started thinking about, so we always have used lead and in fact, we just this week had a conversation about is that the right thing to do anymore when you think about, because I was reading an article about Huns actually and that they tend because they are such foragers, they tend the chicks can end up picking up pieces of old spent lead and obviously we know the stories about that. We have always just used notoriously used lead. I haven’t used bismuth on them.

Hank Shaw:

Bismuth kills them dead pretty good. Steel shot, if you can find Kent Fasteel in fours or sixes, that’s another good non toxic round that works really well especially later season birds

Marilyn Vetter:

You do need a bigger round this late season anyway just because A, they’re a bigger bird. They’re hardier. They take a little more and the last thing you want to do is win them.

Hank Shaw:

Late season birds are always flushing, like it’s a snapshot almost because they tend to be so wary. They’re flushing at your range.

Marilyn Vetter:

They definitely get educated in a hurry.

Hank Shaw:

For sure. So the thing I like about both of these birds is that they’re challenging birds in the kitchen in the sense that you think because it’s a chicken like bird, it’s going to be a white meat chicken like bird and with the exception of the whole roasted prairie chicken, they’re just not there. You likened it to venison. I liken them to doves, actually. A sharp tailed grouse is like a really, really big dove in the sense that it’s a red meat bird that you nailed it. You don’t want to overcook it and if you do overcook, it really becomes a vehicle for whatever sauce or salsa or gravy that you end up putting with it. It’s just kind of like a duck as well, where I’m fortunate enough to live in a place where ducks winter. So they get very, very fat. They don’t tend to be as fat where you live.

Marilyn Vetter:

No, [inaudible 01:06:35] the migration. So yeah, you’re right. In fact, I use a lot of the recipes that I’ve found over the years for ducks on grouse.

Hank Shaw:

It’s pretty good, especially if you’ve got like a skinless sharp-tailed grouse breast, you really need to cook it. If I shot a lot of them, I tend to not shoot a lot of sharp-tailed grouse because that’s just not where I live. So they become this special thing for me, but if I were to shoot a number of them, I would treat them all lot like Arrachera, like skirt steak or flank steak and you take a skinless breast and salt it or marinate it and keep it cold, cold, cold.

You might even want to pound it out so it’s even thickness and then slap that on an incredibly hot, either flat top or grill. Just until you got a char mark and the trick to keeping it cold will prevent it from over cooking by the time you get a good char mark. It’s the opposite of what you would do with a beef steak.

Marilyn Vetter:

That’s exactly what I do. I make my grill super hot and people will be like, wow, that seems really rare. So it can be, but it also when I think about, I’m the only one that’s handled it. I’m not worried about anything else being in it. You are right and then it almost melts, and I haven’t pounded it but that’s a great idea actually because that would help, that clump is part of the breast to respond.

So you wouldn’t have such a difference in the texture and then if you wait too long, the edges are too done and center isn’t done enough but that’s exactly how I like to prepare them the best and then I throw my salad, throw them with a side and I’m really not big into sauces particularly on grouse. So I enjoy the taste but my favorite way is on the grill.

Hank Shaw:

Do you ever make broth or stock with the carcasses?

Marilyn Vetter:

I haven’t really too much, but if I have it’s to make, I use it then as a compliment for like a wild rice.

Hank Shaw:

It’s a really interesting broth or stock, because they’re like all the other grouse, they’re a strong bird. A pheasant stock is effectively like a chicken stock. These stock are not. They’re very much, yes is a prairie grouse stock. It’s going to have that very distinct flavor that either you like or you don’t and it’s one of those interesting things that as hunters we can relate to it. We can liken it to other things, but it would be very hard to describe to a non hunter. It’s sort of funky beefy, more than chickeny.

Marilyn Vetter:

In fact, I always think of it wherever I would need a beef broth is where I would use it. It’s definitely not something you want to surprise your neighbor with if they are not a hunter and you invite them over for dinner.

Hank Shaw:

Here. Here’s my sage grouse or prairie chicken consomme.

Marilyn Vetter:

I’ve learned that lesson a couple of times to not surprise people.

Hank Shaw:

They know better when they come to my house though. It’s like chances are they’re never going to see, I mean, in fact, I haven’t bought meat or fish for the house more than a handful of times since 2005. So they know they’re going to get something wild at my place.

Marilyn Vetter:

They better just show up for happy hour if they don’t Want to eat.

Hank Shaw:

They all eat, because the cool thing is like because I do what I do, it actually is really interesting because it becomes kind of a trust fall situation where if someone’s worried about extra white meat or fish or whatever, they know that if I’m cooking it and I’m going to feed it to them, I’m going to present it in a very accessible and tasty way that if they’re ever going to eat sharp-tailed, grouse or whatever, or you name it, chances are, I’m going to be the guy who’s going to cook it where you’re going to want to try it.

Marilyn Vetter:

If they’re ever going to that would be the time to do it. That is for sure. In fact, you had a recipe I came across this week in your newsletter that I wanted to try with it actually. Goose tacos, and I thought that might be a really great use too.

Hank Shaw:

Absolutely. They’re a little smaller than a big goose. So in that case, if you did that method, you’d want to cook it basically like what we just talked about, which is to say pound it, just so it’s even thickness. So like the thin end of the breast is the same width as the thick end of the breast and cold hot fast. I think on the plancha, like on a flat top or a comal or just a big old frying pan.

I like the flat tops, because it’s easier to flip when you don’t have the high sides and then just chop it. You’ll notice, there’s a green to a bird breast just the way there is with a steak. It’s not as evident, but it’s there. Then that gets, the thing that people, it just drives me batty sometimes like people will take pictures of their tacos or will serve me tacos and it’s like big old pieces of meat.

No, no, that’s not how you do it. Because when you fold a taco and you take that first bite out of a taco, if you can’t, if your teeth can snap right through that meat instantaneously, you’re going to pull out that piece of meat in your first bite of the taco and then the rest of your taco has no meat.

Marilyn Vetter:

I completely agree. You want to experience everything that’s inside that taco in every bite and I don’t want my first bite to be all the meat and the rest just to be Pico or avocado.

Hank Shaw:

Right. Here’s your lesson Ladies and gentlemen, chop your taco meat.

Marilyn Vetter:

We’ve gone a stray but we agree on that completely.

Hank Shaw:

All right, Marilyn, we have run a pretty good time. This has been a little over an hour and before we go, how would people find you on this magical internet series of tubes of ours? Your kennel or social media or you let me know where people should look for you.

Marilyn Vetter:

So, boy, the kennel is a place to find me if you’re looking for dogs, as far as I’m pretty active on LinkedIn, and I’m pretty active on Twitter. So I’m pretty easy to find there.

Hank Shaw:

What is your handle on Twitter?

Marilyn Vetter:

It’s just vetter_marilyn. It’s pretty simple. I wasn’t creative about this one. It was one of those, I need to get on Twitter and oh, shoot, I need a handle.

Hank Shaw:

Mine’s the same. Mine is hank_shaw.

Marilyn Vetter:

I tried to go that way, I couldn’t because somebody had already taken my name. So I had to go the reverse, but those are probably the best and of course I’m pretty active on Facebook and then anything that’s affiliated with PF, QF or NAVHDA, you will find anybody that can track me down. I didn’t want this to go without talking about NAVHDA just a little bit and you have been gracious enough to lend your talents to our magazine and give us a recipe to publish every month and I want to tell you that that is such a hit. You can’t even imagine. People talk about it and wait for it and then compare the notes about the recipes on a regular basis. So I really wanted to thank you for that. It’s really added a lot of robustness and character to the magazine. So I just want to let you know we really appreciate that.

Hank Shaw:

I’m really glad because you guys approached me and I was like, sure, why not. Then I had no idea the kind of response I would get and it’s been surprisingly nice. It’s like, wow, okay, awesome.

Marilyn Vetter:

Well, I think what’s it’s kind of funny is that people do get into a rut about the game that they make. They tend to do it the same way, or they don’t use it. It’s amazing how many people, they go hunting, and then they say, hey, do you want my birds? My family doesn’t like my birds. Well, maybe because you haven’t really thought about different ways to prepare it or they treat it like they treat chicken or anything else.

So I think that’s probably why people have had such a great experience with it is that they feel like they have a level of confidence about, and in a safe way that somebody has already tried out how to prepare their game in a way that not only will others enjoy more, but they will too.

Hank Shaw:

That’s why I do what I do. All my recipes are tested and we talked a little bit before about how rare it is for me to actually kill prairie chickens or sharp-tailed grouse because I don’t live in that part of the world. So every single one of them is a very special thing for me to use. So I think about it and I kind of obsess over those recipes so that they’re airtight, so that if there’s other people like me, who maybe make one trip a year to that part of the world, and you have three chickens or three sharp-tailed grouse, these are really cool recipes that tastes great, where you won’t ruin the result of that very special hunt.

Marilyn Vetter:

Right, or not want to go again. I can’t tell you how many people say I really like hunting the birds, but I don’t like to eat them. So I don’t go

Hank Shaw:

At least they’re smart enough and wise enough to not go I know-

Marilyn Vetter:

I would they do not go and fill their freezer or waste it. Don’t open your freezer a year from now and see a bunch of freezer burned birds that you’re going to toss in the garbage.

Hank Shaw:

Although, before we go one side tip Hey everybody there has probably something freezer burned in your box freezer. It’s really good to make broth or stock out of our soup because freezer burn things, when they’re simmered to make a broth and then you can pick the meat off, no one will notice the difference. Pro tip.

Marilyn Vetter:

I appreciate that. It’s getting that time of the year where I have to make room for new stuff and hopefully make room for some venison soon. So I’ll make sure that I put it aside for broth.

Hank Shaw:

There you go. Well, it’s been a great hour. I really appreciate you coming on the Hunt Gather Talk podcast, and I hope your rest of your season is as good as the beginning of the season was.

Marilyn Vetter:

Well, thank you. It’s been a lot of fun. I appreciate it.

Hank Shaw:

Well that’s it for this episode of the Hunt Gather Talk podcast sponsored by Bilson, and Hunt To Eat. I am your host Hank Shaw and you can find me on social media at the hunt gather cook forum on Facebook is a closed forum. So tell me in the questions that you have to ask to get into the forum that you heard about the group from this podcast and I will let you in. I am also very active on Instagram where I’m also huntgathercook. You can find me there pretty much every day posting cool stuff and good things to eat.

As always, the core of what I do is Hunter Angler Gardener Cook. It is huntgathercook.com and you will find that it is the largest source of wild food recipes on the internet in any language. I hope to see you there at huntgathercook.com, @huntgathercook on Instagram, or in the Hunt Gather Cook group on Facebook. Until next week, talk to you later. This is Hank Shaw. Bye.

First off, great podcast! I’m a fan of all your work.

But what a HUGE bummer on the ignorant comments regarding prairie dogs. It’s fine to hunt them of course (I’m not anti!), but referring to them as ‘pests’ on a podcast about prairie grouse is truly perplexing. Consult ANY grasslands ecologist and they will tell you that across most of the Great Plains one of the fundamental requirements for fully intact ecosystems is that they MUST include prairie dogs. They evolved with the grasslands, along with large ungulates such as bison and elk, and are an essential component to a healthy landscape. The misinformation purported by your guest on this episode greatly devalues an otherwise excellent podcast since now we have to wonder what else you guys got totally wrong.

Joey: Marilyn is the daughter of a rancher, not a biologist, so she will have a different perspective. I understand that they are native and have a place in the grasslands. But she is entitled to her opinion as much as you are yours. From a rancher’s perspective, prairie dog towns kill their livestock and sometimes their horses when a cow or horse steps in a hole and breaks its leg. As for me, I am not in the habit of shooting them, or ground squirrels, and the story I told was to relate a real case of frustration and exhaustion. I am the first person to acknowledge that I am not perfect, but then neither is Marilyn, or you.