As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

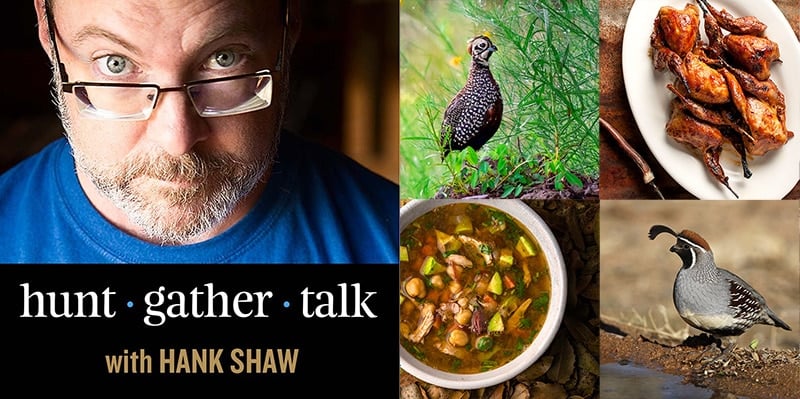

If you haven’t noticed, Hunt Gather Talk is something of a quail podcast. I’ve done whole episodes on several of the various species, like bobwhites, mountain quail and the like. This episode is all about the desert quail: Mearns and Gambels, with a smattering of scaled quail talk.

I talk with hunter-biologist Kirby Bristow of the Arizona Dept. of Game & Fish for this one. Kirby has been hunting and studying desert quail since his youth, and knows more about them than just about anyone.

Every episode of Hunt Gather Talk digs deep into the life, habits, hunting, lore, myth and of course prepping and cooking of a particular animal. Expect episodes on pheasants, rabbits, every species of quail, every species of grouse, wild turkeys, rails, woodcock, pigeons and doves, and huns. Thanks go out to Filson and Hunt to Eat for sponsoring the show!

We get into the biology of these quails, their habitat, how to hunt them — and which ones you can chase successfully without a dog, as well as a healthy conversation about cooking and eating them.

For more information on these topics, here are some helpful links:

- My story on hunting Mearns quail in Arizona.

- A good overview about the biology of the Mearns Quail, and also the Gambels Quail, from Cornell University.

- Tips on hunting desert quail, from Project Upland

- More tips on hunting quail, from the Arizona Game & Fish Dept.

Recipes

- You can find all my quail recipes here.

- This is the ode to the Sonoran Desert I mention in the podcast.

- Here are my instructions on how to pluck a quail.

A Request

I am bringing back Hunt Gather Talk with the hopes that your generosity can help keep it going season after season. Think of this like public radio, only with hunting and fishing and wild food and stuff. No, this won’t be a “pay-to-play” podcast, so you don’t necessarily have to chip in. But I am asking you to consider it. Every little bit helps to pay for editing, servers, and, frankly to keep the lights on here. Thanks in advance for whatever you can contribute!

Subscribe

You can find an archive of all my episodes here, and you can subscribe to the podcast here via RSS.

Subscribe via iTunes and Stitcher here.

Transcript

As a service to those with hearing issues, or for anyone who would rather read our conversation than hear it, here is the transcript of the show. Enjoy!

Hank Shaw:

Kirby Bristow, welcome to the Hunt Gather Talk Podcast.

Kirby Bristow:

Thanks, Hank.

Hank Shaw:

I am very happy to have you on because not only am I super fond of hunting Mearns’s and scaled quail and Gambel’s quail and pretty much every other kind of quail there is, but my friend Jonathan O’Dell said you were the guy to talk to who really knows these birds in their environment, so tell us a little bit about what you do in the Arizona Game and Fish Department. And I imagine you are also a quail hunter, right?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. A little bit about my history in Quail Management in Arizona, I guess. In 1979, after years of research on quail and the impacts of hunting on quail, and various different management efforts to assess the impact of harvest on quail, in 1979, The Game and Fish Department had lengthened the season and increase the bag limit to about the state that it’s in now where we have a season that starts in early October and goes to early February with a 15-bird bag limit. That year was also the first year that I ever trained a bird dog. It was also the year that we set the record for state harvest, estimated state harvest based on 100 questionnaire data.

And the reason for that is partly because of the relaxed regulations, but also because of a bumper crop of quail that we had, largely in response to the favorable conditions, specifically, winter precipitation. We’ve had multiple years of good winter precip in a row, and that resulted in a bumper crop of Gambel quail specifically and that’s largely the primary species that’s harvested in Arizona. And so, I kind of started, got an early start with a love of quail hunting and it happened to be timed precisely when quail numbers were up and so naturally, I became very interested in quail hunting and have quail hunted every season since then.

Hank Shaw:

You were probably a teenager in ’79, right?

Kirby Bristow:

Yes, I was 14, 15 years old during that season, and I lived in North Tucson and I would go quail hunting from my house. I could walk from my house and quail hunt every afternoon after school, so-

Hank Shaw:

I bet you that area right now has got houses on it.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. There’s multiple places where I used to quail hunt that has houses and/or golf courses. But yeah, there’s lots of Gambel quail habitat across the state and so, you just have to move your hunting areas. Yeah, so that’s, it’s natural that I would have become an avid quail hunter given that history and when I got out of school-

Hank Shaw:

To go to Arizona?

Kirby Bristow:

I went to the Northern Arizona University for my undergraduate degree and then, the U of A, graduated from the U of A in 1993 with my Bachelor’s. All right, man. I’m sorry.

Hank Shaw:

Wow, you’re kind of a homer, like your whole career is in Arizona?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. In fact, my father moved here in 1962 to work for the Arizona Game and Fish Department and then we actually, we lived at the Cluff Ranch Game and Fish Department property when I was born near Stafford, Arizona. So yeah, my entire life history has been with Arizona Game and Fish Department and a lot of that has revolved around quail and quail hunting. In the late ’90s, I started doing research on quail species, Mearns’s quail and scaled quail specifically. And so, I worked with the Arizona Game and Fish Department research branch for most of my career span, during a good part of that, I’ve worked with quail species. I have since helped a little bit on the Masked Bobwhite recovery effort. I’m on the Masked Bobwhite recovery team and I’ve been interested in quail research and quail management in the state for a long time now.

Hank Shaw:

So, let’s step back for a second because one of the things about this particular season of the podcast is that I’ve been going into depth with specific species, but there are some broader brushstrokes that I’ve been touching on during the season as well, and that is that north of a certain line, the environment is filled with different kinds of grouse. In South of a certain line, the environment is filled with different kinds of quail. So, you have a smaller bird and a bird that is less cold hardy, that’s kind of the extent of my knowledge of it.

What is the break point? What shifts the gallinaceous birds, the chicken-like birds from all being quail to all being grouse? I mean, because Arizona does have some bluegrass way up by Flagstaff, but an Arizona grouse hunter is a rare thing as opposed to a quail hunter, so you’re kind of at the breakpoint from a latitude standpoint. You can go all the way across to the Atlantic Ocean and you’re pretty much in quail country and not in grouse country, is it a heat thing or what breaks the quail line from the grouse line?

Kirby Bristow:

I think you’re exactly correct. I think it is a heat thing. I think birds of a smaller size, these are not migratory birds and so, they have to withstand conditions for the entire year in the area that they exist. And so, birds of a smaller size are less able to withstand the cold and so, like you pointed out as you go farther north or as you go higher up in elevation, you find that the quails drop out and they are replaced largely by grouse ptarmigans as you go extremely far north.

Hank Shaw:

Well, ptarmigan is a grouse, too, so that counts.

Kirby Bristow:

Right. Yes, yes.

Hank Shaw:

So, it’s body mass, so it’s the ability to retain heat during the cold.

Kirby Bristow:

That’s my opinion, but to be… I’m sorry. That is what I think is probably going on, but again, I don’t know that I’ve looked closely at that question, but that’s my guess on what’s going on.

Hank Shaw:

It’s interesting, because there is one exception to it. Well, there’s a couple of exceptions to it, if you think about it. One, pheasants do quite well in the human area. That’s probably largely because of human interference because of the agriculture and irrigation.

Kirby Bristow:

Right. Yeah. And at one time we had tried to introduce pheasants everywhere. We had farm country, and they really only hung on in the Yuma area. I’ve heard that there may be some relic pheasants still in the Hilo River Valley and maybe even the Verde Valley along the Verde River, but yeah, the only place where they exist in any numbers, in any huntable numbers is over there by Yuma. Yeah, Dave Brown’s thought was that that was they needed the increased humidity right along the river in order to nest successfully.

Hank Shaw:

So, the reverse of that is the presence of the Hungarian Partridge, which I just actually got an opportunity to hunt up in North Dakota and they exist all the way up into Canada. So, we know them as the quail of the North and it’s interesting because they’re kind of that small body exception in a very cold place.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah. Yeah, they’re still larger than quail, but yeah, compared to grouse, they’re very small. And both of those examples, the pheasant and the Hungarian Partridge are introduced nonnatives and so, that may have something to do with why they don’t seem to fit the rest of the pattern because they did not evolve here, they were introduced.

Hank Shaw:

I bet. So, that brings us to the specialness of Arizona and quail. I mean, to my knowledge, there isn’t really any place except for I mean, maybe New Mexico that has that kind of a spread of quail species, so I mean, you’ve got the three huntable… well, really four huntable ones if you had some vagrant California quail that show up near the Colorado River and then you’ve got lots of Gambels, lots of Mearns’s quail, a fair number of scaled quail, and then you’ve got the non-huntable Masked Bobwhite, which we should talk about a little bit, just as a side note, because it’s kind of cool. But why, I guess the question is what’s so special about Arizona that has all these different species, pretty much cheek by jowl like you can, in theory, get all three species in one day?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, I think what’s unique about Arizona is the diversity of habitats that we have and that diversity is driven by the change in elevations that we have available to us. They do have four huntable quail species in New Mexico and they’re the same species, well, actually they have Bobwhites in New Mexico, so they have scaled quail, Gambel quail, Montezuma quail and Bobwhites in New Mexico. A friend of mine actually did the four species New Mexico quail hunt and sent me a picture of his successful hunt. It took him several years of trying before he could finally put it together. And when I asked how far he had driven to make that happen in one day, he said it was 500 miles.

Hank Shaw:

Wow.

Kirby Bristow:

So that situation, they all exist in New Mexico, but you have to travel quite a bit of difference as opposed to Arizona where you have, like you were pointing out, you can actually find all three species in one parking spot. I found that on occasion, scaled quail, Gambel quail and Montezuma quail that I can hunt from one parking spot. That’s a bit of a rarity and it’s often not the best habitat for any of the three, so you might not have good numbers for any of the three, but you can indeed find them overlapping like that in Arizona. And it’s like I said it’s because of the diversity of habitats that we have. The ranges of those species all overlap in Arizona. We’re at the heart of the Gambel quail range. The majority of Gambel quill distribution is in Arizona, the majority of Montezuma quail distribution in the United States is in Arizona. A good fortunate-

Hank Shaw:

Let me stop you for a second. So, for the listeners who may not know the bird in Arizona tends to be called a Mearns’s quail after a guy named Mearns, and the same bird, the exact same bird everywhere outside of Arizona is typically called a Montezuma quail. It’s the same bird. That’s just a side note as we go forward.

Kirby Bristow:

Tactically, the name Mearns is more correct, because it is the Mearns subspecies of Montezuma quail. So, Montezuma quail is more of a general term that refers to all of the subspecies of that species and the Mearns is the only subspecies that exists in the United States. The other sub species, they’re all down in Mexico.

Hank Shaw:

And they go all the way down like Guatemala, don’t they?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, they go quite a ways down into Mexico and there, as you get down towards those tropic areas, the diversity of subspecies increases. There’s quite a diversity of quail as you go farther south into Mexico.

Hank Shaw:

Isn’t there one called like the splendid or the elegant or the excellent quail or something like that?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah. There is an elegant quail that lives in the Thornscrub habitat of Mexico, but I’ve also heard people claim that they’ve seen them in Arizona, but from what I’ve seen, the distribution of elegant quail is well below the Arizona-Sonora border, so I can’t imagine that there’s been any natural occurrence of elegant quail in Arizona.

Hank Shaw:

So, before we get into the huntable ones, let’s talk a little bit about that Masked Bobwhite, because I got the opportunity to see one. It looked very frightened. It was sitting in a box at the Quail Fest in Sonoita when I was there last year, I guess it was. Not this, yeah, no, yeah. Well, my God, it wasn’t February. Yeah. God, how time flies in the time of Corona and it’s this cool looking little Bobwhitey thing and it seems to be a pocket right near Arivaca in sort of South Central Arizona. And then, so there’s a pocket in the U.S. and then is it more common in Mexico and sort of in this one spot, it just happen to the only place it exists north of the border, is that the case?

Kirby Bristow:

Their historic distribution was pretty limited to begin with, but most of their distribution was down in Mexico and there was just like you say a pocket up in… there was a Masked Bobwhite in the Altar Valley, which is where you’re talking about. And so, in the grassland habitats in those regions of the state, they existed, but that Santa Cruz Valley is. Now, all of the grassland habitats and there have been either changed to agriculture or they’ve changed. They’ve become more shrub encroached or tree encroached, and so, there aren’t any Masked Bobwhite occurring there.

Hank Shaw:

So, you were saying about they’re only in that one little area now.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah. And unfortunately, that’s probably the only place that they exist in the wild. We have done some surveys down in Mexico, near a town called Benjamin Hill, where the last wild Masked Bobwhites were occurred, but most of the most recent surveys have not detected Bobwhite quail down there, so population that is on the Buenos Aires refuge is likely the last “wild” population and that is, I’m doing air quotes when I say wild because that is largely the result of release from pen-raised birds. And so, they’re struggling.

Now, we’ve had some success including some natural reproduction in the wild, documented on the Buenos Aires refuge recently and that’s the result of some pretty concerted efforts to both change the habitat back to a more grassland, shrub land type that was present back at the turn of the 19th Century as well as concerted efforts to reintroduce these pen-raised birds using various methods of fostering chicks with wild adults in order to enhance their survival. So, they are making success, but it’s slow progress.

Hank Shaw:

So, you mentioned the grass and that immediately pricked my ears up because as a quail hunter in that part of the world, I know that the Mearns’ quail is your grasslands quail, so you’ve got these kind of three major habitat types, we’re going to get into in a second, but Mearns was kind of a little bit higher elevation, you’re looking at grass, you’re not really looking at heavy cactus. This kind of lowland heavy cactus is kind of your Gambel’s quail’s turf, and then if you see a bunch of yuccas around, that tends to be your scaled quail tier. Let’s talk about the Mearns quail for a second in the sense that, okay, so that’s a grasslands quail, how does the habitat from this Masked Bobwhite, which is super endangered, how does that compare to the Mearns quail habitat which it seems like it would overlap, right?

Kirby Bristow:

Of the quail species that overlap with the Masked Bobwhite, the Gambel’s quail might actually be more similar in habitat. The scaled quail exist in a sort of a shrub-encroached grassland. It wouldn’t be a pure grassland where there’s nothing, but grass and nothing else, but it definitely doesn’t have a tree component to it. You can have shrubs and fairly dense shrubs sometimes about head high, but you get any more of a tree component than that and the scaled quail draw up.

The Gambel quail is more of a Sonoran Desert scrubland, I guess, where you have lots of cactus and you have sometimes a pretty dense tree canopy, but you’ll have Palo Verde than the mesquites and ironwood trees. And then the Masked Bobwhite was more of a shrub-encroached grassland similar to what the scale quail are using, but it was more isolated to the riparian corridor, the wettest parts of those grasslands. And then the-

Hank Shaw:

The Mearns likes spokes, right?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah and Mearns are Savannah than a grassland, where there are oak trees and they will feed on acorns, Mearns quail will feed on acorns, but that’s not the reason that they exist in the areas where the oaks are, because the majority of their diet are these underground bulbs and tubers that they dig up with their elongated claws. And so, it’s more the microhabitat that the oak trees provide that allows the growth of those forbs that produce those tubers, that’s the more important part of the oaks in the habitat rather than providing acorns for feeding.

Hank Shaw:

Got you. So, as a hunter, you’ve hunted all these species, except for probably Masked Bobwhite. What would you say is the difference in terms of character of these birds? I ask this question a lot of people who hunts the game birds that we all hunt and different birds have a different kind of attitude or different character or a different kind of, some birds are wily, some birds are just super skittish, some birds are kind of arrogant. And so, you’ve got these three major ones in Arizona, the Gambels, the Mearns, and then the scaled, how would you say that if you’re going to have them, how does your attitude change and how do you perceive the attitudes of these particular birds when you’re out in the field chasing them?

Kirby Bristow:

The Gambel’s quail are the most gregarious of the quail that is that they like to be in large group and so, you can take advantage of that as a hunter by learning to recognize their calls and being able to imitate their calls and get them to respond back. I often say if somebody is talking about Gambel quail hunting, wanting to go Gambel quail hunting for the first time, I advise them to get a call and learn how to use it because it can help you identify where the birds are. They also tend to be likely to run, not hold tight, but they will hold tight once they are broken up into singles.

Hank Shaw:

After you do the initial flush, then you can go after the singles a little bit better with a dog?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. And they will hold very tight as singles and sometimes, this is one of those “Do as I say, not as I do,” but it’s often best if you don’t shoot it at covey rise because the covey will get up out of range oftentimes and if you scratch down a bird on the covey rise then you have to divert your attention to where that bird went down, you might not see where the covey flew to. And if you can mark down where a covey goes down, that is where you’re going to get your better shooting opportunities is on those singles because those birds will hold tight and not flush out of range. Now, that’s a generalization. There still will be individuals that might flush out of range as singles, but in general, they’ll hold much tighter as singles and that’s where you get your better shooting opportunities.

The Mearns quail is quite the opposite. They are very cryptic and they rely on their camouflage to escape predators, and they will hold tight as a covey and let you walk right by them, and without a dog, you would never know that they’re there. In fact, many people who first encounter them without a dog remarked about how they nearly stepped on them before they flushed. And it wasn’t really until we had guys hunting with pointing dogs that it was originally thought that Mearns quail did not exist in high enough densities to allow hunting harvest and it was bird hunters who would introduce the fact to the Arizona Game and Fish Department that indeed, there are huntable numbers but in order to find them, you have to have bird dogs and if you go in the field with a good pointing dog, you’ll be able to find coveys.

Scaled quail, they are the track stars of the quail world. They run a lot and again, they’re like Gambel quail in that they’ll run and flush out of range as a covey, but once you get them broken up into singles, they’ll hold tight enough that that’s where your best shooting opportunity will be, but sometimes it takes several flushes to get the scale quail broken up enough where they will hold tight. You’re better off with several people going after a covey, so that you can spread out and keep track of them and move the birds around and it kind of takes a concerted game plan to work a covey good enough to where they’re broken up, and you’re getting shots at singles then.

Hank Shaw:

So it’s my impression also that the Gambels and the Mearns typically don’t flush all at once. They’re not like Bobwhites or Hungarian partridge in the sense that they’re pretty much all going to flush at the same time. Now, with those two birds, there might be a straggler or two, but my experience both Mearns and Gambels is that there’s going to be a flush, but there’s always going to be multiple birds that didn’t get the memo.

And so, another trick that I’ve used both the desert and in other places is that if I don’t catch them on the flush, I just stand there and be ready and watch where the main bunch of birds flew off because somebody’s going to get up like, “Oh, now” and you’ll get that shot of the stragglers and there’s often a good… I mean, with Gambels, God, you could often have a half a dozen stragglers and with Mearns, there’s typically one or two because they’re much smaller covey, like correct me if I’m wrong, but like a really big Mearns coveys, we’re typically flushing eight to 12s in my experience. They’re a bit more like mountain quail in their tiny coveys, whereas Gambel’s quail with their big coveys are a little bit more like California quail.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. In fact, well, on Mearns quail, I think it’s true of all quail, like you were pointing out as far as there’s often a bird that a few birds that flush early, and sometimes they flush out a range, and sometimes on Mearns quail, if I was lucky enough to scratch one of those birds down, it’s often the adults, the Mearns quail coveys are generally just a pair and they’re brood from that year and that’s why you have the smaller covey sizes that you were talking about. And yeah, a covey size of 15 is a big covey for Mearns quail.

And whereas Gambel quail, there’ll be multiple adults with their broods from that year and so, you’ll have covey sizes of 20, 30 and sometimes up to 100 birds and their really good years. And so, when I’ve paid attention on Mearns quail, if I was able to shoot one of those early flushing birds, it’s often the adult. I may be giving them more credit than its due, but it’s almost as if they’re going to take that to the rest of the covey so you’ll be standing there with an empty gun when the easy birds flush. It’s so [crosstalk 00:26:13].

Hank Shaw:

Or it could be in a case where like the adults like, “I’ve seen this game before, I know how it ends. I’m getting out before the whole-”

Kirby Bristow:

That could be, that could be why they’re adults, too. It’s how they were able to survive to that point is they flush well, but yeah, it’s another one of those, “Do as I say, not as I do.” If you can hold your fire on those first couple of birds that get up, the easiest shots are often those stragglers that you’re talking about, but usually, in my experience, I’m standing there with an empty gun hurriedly trying to reload as the easy birds are flushing at my feet.

Hank Shaw:

It’s generally known that if you’re going to Mearns quail in Arizona, you generally want to go to the southern part of the state, really the south central to south east part of Arizona for Mearns.

Kirby Bristow:

Right.

Hank Shaw:

The scaled quail are pretty much in only the eastern part of Arizona and Gambels are like everything south of Flagstaff, is that about right?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, essentially. The Gambel quail range includes all of the Sonoran Desert as well as the Mojave Desert all the way up into Kingman. And then the Mearns quail distribution is mostly limited to those oak woodland type areas. The western edge of it is the [inaudible 00:27:35] Mountains and then it goes all the way to New Mexico border. And then it goes as far north as beyond rim, but the highest numbers are down in that southeast corner.

And then the scaled quail range is similar to that, that I just described for the Mearns quail, but they’re in the lower elevation grasslands of that same part of the state. And mostly in the southeastern corner. The heart of scale quail distribution is really New Mexico in the Chihuahuan Desert and it’s like you saying if it’s an open grassland with some yuccas that’s a good indicator of scaled quail habitat in southeastern Arizona.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, I interviewed a guy named Ryan O’Shaughnessy for a whole episode on scaled quail, and he is a South African, who has a Ph.D. in Gamebird Biology who’s also an outfitter in West Texas.

Kirby Bristow:

Okay.

Hank Shaw:

So, he’s kind of a unicorn in that sense.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah, that’s an unusual.

Hank Shaw:

Here’s the thing that’s been, this is just as a personal question for me, because I’ve just been fascinated by it. Why are Gambel’s quail and valley quail, so similar?

Kirby Bristow:

That is a good question. I’m not familiar with their evolution, but I would think that it’s possible that there was some barrier and maybe it was a Colorado River that separated those two very closely linked species and caused them to diverge into two different species, so there must have been a historic ancestor fairly recent in geologic terms that was separated by some barrier perhaps it is the Colorado River and it caused the two species to diverge in fairly recent geologic history.

Hank Shaw:

Because, yeah, I mean, if you don’t know what you’re looking for, they look like the same quail.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah. And they behave very similar. The call is almost indistinguishable.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, you can use the same call for either and I actually have two different calls. I’ve got one by a guy named Jim Matthews who lives in Southern California and then, of course, the Primos calls. Well, both of them are good calls for both kinds of quail. Now, Ryan O’Shaughnessy said that scaled quail don’t really talk much and they don’t come to a call, do Mearns?

Kirby Bristow:

Mearns are even less talkative in scaled quail. Scaled quail, you can get to answer after you’ve broken up a covey. Sometimes, you’ll hear them answer and Mearns quail almost never do you hear them call. It makes it difficult for biologists to study Mearns quail because there’s not a reliable population index. Gambel quail call in the springtime, loudly and frequently enough that it can be used as an index of what the next year’s population is going to be, but when they tried to do that with Mearns quail, they weren’t able to. It’s not very loud, so it doesn’t carry very far and they just don’t do it consistently enough.

There’s been rare times when I’ve been able to recognize the Mearns quail call and go to that area while hunting and find a covey. Whereas I would say most of the time with Gambel quail, I’ve heard them calling before I found the covey.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, I mean, if you watch the nature shows on TV that are set in the Sonoran Desert or the Mojave, if you listen to them, you’re hearing cactus wrens and you’re hearing Gambel’s quail. That’s set in the background music of that. They may be showing you some other animal, but in the background, there’s probably going to be one of those two birds calling.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yep, yep. And they often use it as the sound of the West in many TV shows, and even when it’s incorrect. I think I’ve heard them calling in Little House on the Prairie, which is supposed to be South Dakota, so they’re way off on that one.

Hank Shaw:

Well, it’s like the pet peeve of every falconer on the planet when on TV, they show bald eagles making the same noise as a red-tailed hawk.

Kirby Bristow:

Right, right. Yep.

Hank Shaw:

Because bald eagles have this weird little chippy sound and the red tails got the hawk sound that is in everybody’s mind right now.

Kirby Bristow:

Right, right.

Hank Shaw:

Speaking of hawks, my guess is that raptors are the single biggest enemy of all of these species of quail or is there something different?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, as far as adult mortality, raptors are almost the single source of adult mortality and for a species like Mearns quail that are dependent on that, that behavior that I talked about where they just hunker down and hide, that behavior is so ingrained that they will do that and eat when there is no cover available. And so if you’ve ever on the rare occasion, when they venture out onto a road, if you see Mearns quail on the road, oftentimes, the covey will just hunker down right in the middle of the road where there’s absolutely nothing to hide behind because that is their escapement mechanism.

Hank Shaw:

That is not ideal.

Kirby Bristow:

No, it’s not ideal and it’s especially problematic when you’ve got overgrazed habitat. Some of the researchers back in the ’70s and ’80s found that those tubers that they feed on are actually more prevalent in grazed areas, but in overgrazed areas, the bird numbers, birds were absent from overgrazed habitats. So, the need for the grass is not so much for their diet as it is for the cover that keeps them hidden from the aerial predators like raptors. Conceivably, there would be an ideal level of grazing where you might maximize the food resources without removing too much cover.

And so, that’s what some of our research was designed to do is to try and provide guidelines for the Coronado National Forest to implement in order to protect cover for Mearns quail while still allowing public land grazing. And so, I think they’ve done a pretty fair job of that and no doubt, there’s areas that are overgrazed, but they’ve been pretty responsive. If you looked at a distribution map of Mearns quail in Arizona, it would almost exactly overlap that of the Coronado National Forest as soon as you get-

Hank Shaw:

Good to know.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, and if you have a Coronado National Forest map, you’ll see that it’s a bunch of little islands and it’s all just about any place on the Coronado National Forest in Southeast Arizona, you’re likely to find Mearns quail if you look hard enough.

Hank Shaw:

The conservation status of all three of these birds, kind of not nationwide is, I understand that it’s with most gamebirds, it’s a habitat issue. The Mearns quail has been heavily studied and is actually being more managed in the last 20 years, and I guess it has been in historically. What are the populations doing of all three of these species? Are they going up? Are they steady? Are they going down?

Kirby Bristow:

The Gambel quail, it’s probably, it’s the generalist of the three species and so it’s able to exist in a wider variety of habitats and for that reason, it hasn’t been as impacted by land management activities as the other two, which are more specialist. So, the Gambel quails, they’re doing well, except they are dependent. Their numbers are dependent on winter precipitation and over the last decade, we’ve had pretty poor winter precip.

The last couple of years were average to above average for winter precipitation. So, this fall, we should have better Gambel quail numbers, but over the last decade, and perhaps even more than a decade, it’s been largely dry winters and we’ve had pretty poor Gambel quail numbers, but their populations are healthy in that they’re hanging on in the areas where throughout their range, they’re sustaining populations, but just not high numbers.

Hank Shaw:

They’re the only species of quail that I know of that really loves hanging out in Arizona subdivisions.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah. Yeah, they do well in subdivisions, they do well along golf courses, and so, yeah, because they’re such generalists. They’re able to, to exist in a variety of habitats. You’ll find them at elevations upwards of 7,000 feet.

Hank Shaw:

Really?

Kirby Bristow:

In Pinyon-Juniper habitat, all the way down to the lowest, almost sea-level areas and so, they can exist over a large variety of habitats and yet their numbers are generally determined by that rainfall that falls between [inaudible 00:37:29] and March.

Hank Shaw:

Between when?

Kirby Bristow:

October and March, October and the following March and as you go from Southeast Arizona to Northwest Arizona, the percent of rainfall that falls in the winter versus summer increases as you go Northwest. So, in the Mojave Desert, which is the northwestern part of the state, a higher percentage of rainfalls in the winter than in the summer, around the middle part of the state, Phoenix-Tucson area, it’s about half and half and then at the southeast part of the state, there’s a higher percentage of rainfall falling in the summer versus the winter.

And so as you go across that same range, in terms of Gambel quail numbers, oftentimes your Gambel quail numbers are more consistent up in that north and west part of the state. You can have some excellent hunting for Gambel quail in southeast part of the state, but on a year to year basis when you have dry year, dry winters especially your Gambel quail numbers will be better in that northwestern part of the state.

Hank Shaw:

Good tip.

Kirby Bristow:

And the scaled quail are across their range, they are decreasing and it’s because they are sort of a grassland or it’s sort of a shrub-encroached grassland habitat that they’re adapted to and through fire protect protection and grazing over several hundred years, a lot of the grasslands have been converted into shrub lands with mesquite encroachment and Juniper encroachment. And when that happens, there’s a lot less of those trees like mesquites and Junipers, they take up a lot of water.

And so, the areas that have been encroached by mesquite and Junipers tend to have drier, less water near the surface and so, there’s less forbs and grasses, which are provide the feed for the quail. And so, those areas tend to become kind of a monoculture of just mesquite trees and dirt. And so there’s big efforts to try and revert those areas back to grasslands, but it’s pretty difficult in terms of you have to cut down the trees or you have to treat with herbicides, or you have to pull the trees up by the roots. The mesquites are particularly good at re-sprouting from stumps and so, it takes a lot of effort to revert those habitats back to grasslands. [crosstalk 00:40:22].

Hank Shaw:

It’s a lot like with the sage grouse up north in the Great Basin. They’re having issues with Juniper and conifers as well and it’s virtually the same thing.

Kirby Bristow:

Yep, yep. So, it takes more effort to build those habitats back up. And so, for that reason, the scaled quail numbers have been declining across their range.

Hank Shaw:

So, let’s talk about a hunting issue that I talked with Dwayne Elmore. He’s a Bobwhite biologist, and he says with Bobwhites that if you have contiguous habitat, so if you have a big swath of an area of which there are multiple coveys that could in theory, walk up and talk to each other, that the concept of shooting out a covey is false. So, there’s this hunter idea that, “I don’t want to shoot that covey out, so I’m only going to hunt it once and I’m never going to go back to it again in that season.” And so, what Dwayne says is that that’s just a false thing unless you’re dealing with isolated [inaudible 00:41:34] habitat, where a particular covey of quail can’t talk to somebody else. So, what he’s saying is that with Bobwhites, they are fluid. And what I wanted to know is, is that the case with these three quail as well?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, I would say that is definitely the case with Gambel’s quail and scaled quail. You might think otherwise with Mearns quail because they do tend to exist in a habitat that’s more isolated, I guess you could say. Like I was saying earlier, the map of the Coronado National Forest is a bunch of islands of forest land in this sea. It’s the sky islands, they refer to it, as all these mountain ranges in southeast Arizona. However, the recent information on movements as well as some research that we did has shown that their ability to move is greater than we previously and their resilience to hunting pressure is similar to other quail species.

We had done some research back in around 2000, so 20 years ago, where we were looking at bird numbers, both before and after the quail season in both hunted and unhunted areas and we found that while the unhunted areas were better able to maintain quail throughout the season, bird numbers would be similar or actually higher in the hunted areas the following season. And so, there would be a threshold level at which if you remove the birds, it would likely affect the following year’s population, but that hasn’t occurred or wasn’t occurring from the normal hunting harvest that we had during that study.

What it really says is there’s factors independent of hunting that are really driving the bird numbers on a year-to-year basis. Now, that said, we did show a decrease in areas, in terms of bird numbers. So, you started out this season and in one canyon, we were encountering more birds at the beginning of the season than we were at the end of the season. And I’ve noticed that during hunting seasons, and it does seem alarming, because you get to the end of the season and it’s very difficult to find Mearns quail in heavily hunted areas. But if the conditions are right, the next year, those bird numbers are back up again, where they were.

Hank Shaw:

Interesting. It’s also probably the reason why you set the bag limit on Mearns quail is eight, right?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, and that as far as biologically, quail are considered self-limiting in that it becomes so difficult to bag. They’re such a small percentage of the hunting population that bags more than four or five birds a day that a bag limit of 50 is similar to a bag limit of five, because there’s just not very many people that achieve more than five anyways. You’re not going to affect the harvest unless you really drop the bag limit really low.

Hank Shaw:

I’ve seen that with duck management, too. In fact, with ducks, there are some places that are talking, just starting conversations about the concept of a splash limit, which is to say, you can shoot five birds of any species, and it doesn’t really matter as opposed to seven in the pacific flyway of specific species, because they’re coming to that same conclusion that a hunter effort and the number of hunters, who are actually… it’s like the old saying, it’s 10% gets 90%, or whatever variation on that you want to say is. There’s a hardcore of X hunters, who get Y percentage, which is the lion’s share of any given overall harvest of any given species.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, and so, what really drives the total harvest is the number of hunters of field and that is often self-limiting because word gets out, “This is a bad year for quail,” the hardcore people that you’re talking about go out every year, they tell their friends, they blog about it, they put it on social media. And then those people that are less driven to hunt every day of every season, they see the news that it’s going to be a bad year, and they pursue something else. And so, the hunter effort is largely driven by that availability of birds and so, it almost becomes self-limiting, self-regulating.

Hank Shaw:

I have seen something with Mearns quail though that’s interesting over the last six or seven years and in that, I have seen hunter effort on that particular species go way up for a couple of reasons. One, I think it’s kind of been discovered by the greater uplands public in the United States, but two, there’s something special about hunting Mearns quail, in that if you have a good solid dog and say North Dakota or Texas or Ohio, you can hunt Mearns quail. You can’t really say that of Gambel’s quail. I mean, because if you have that same good solid dog from North Dakota and you take it Gambel’s quail hunting, it’s going to be covered in cactus and cholla and it’s going to be super not happy and you go on a very short hunt.

So, I guess what I’m saying is with scale to some extent, but definitely Gambel’s quail, you kind of need an Arizona dog or where a dog is used to that particular environment whereas you can travel to Mearns quail country from another part of the country and successfully hunt Mearns quail with a dog that’s never seen southeast of Arizona.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, I would agree. There is a learning curve or a period of getting… I think every time that I’ve taken my dogs out after a new species, there is a brief time where they’ve got to figure out what this bird does in may be a day or two, but yeah, definitely Mearns quail, they hold tight, they’re the perfect bird for pointing dogs, and I agree there has been an increase in interest in hunting Mearns quail. I think because the word has gotten out that there are a lot more people hunting, but I think their harvest is still commensurate with the bird numbers that is in good years, everybody does well and in poor years, the harvest is very low. And so, a bag limit really only affects a lot of people when bird numbers are really high. There’s only a few years when the bird numbers are so high that there are a lot of people reaching that bag limit.

Hank Shaw:

And this is not one of them.

Kirby Bristow:

And this is not one of them. Mearns quail are dependent on monsoon or summer rains and this year was the second driest in history. And last year, last year was not really good, but it was about average, I would say from Mearns quail. And so, yeah, this next year is not going to be good for Mearns quail.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah. I watch the monsoons in Arizona for two reasons. One, I pick edible mushrooms and so, a lot of times I like to go to the White Mountains or something like that if it was a good monsoon year. And so, I’m watching, watching, watching and then nope, there are no monsoons this year. And then of course, the Mearns quail in the dead of winter depend on those summer rains as well.

Let’s talk a bit more about dogs. You’d mentioned that Mearns are perfect for pointing dogs, are all three of these species really kind of pointing dog birds or are flushing dogs just as good?

Kirby Bristow:

Generally, I would say that if you’re going to use a flushing dog, you might be better off sticking to Mearns quail, that’s a pretty general statement, because it all depends on where the birds are. If you’ve hunted Mearns, quail, a lot of Mearns quail country is these long canyons kind of the foothills of the mountains. The best place to hunt Mearns quail are these kind of rolling hills with oaks and the oaks will tend to be on the north facing slopes and the south facing slopes will be opened.

Unfortunately, the quail tend to be up under the Oaks. And so, when you do get a flush, even though they’re right at your feet, they’re often through trees and around a tree and behind a tree, so even though you had a whole covey flushed in range, you might not get a shot at any of them just because of the tree cover. A lot of guys who hunt rough grouse say that, “Yeah, that’s the same thing. You just got to swing and shoot and ignore that the tree is there.”

Back to the flushing dog. You might think that a flushing dog would work fine with Mearns quail because they’re always flushing fairly close to you, but if the dog flushes when you’re on the wrong side of the tree, you won’t get a shot. And so, I think having the controlled situation with a pointing dog is better even for Mearns quail.

Gambel’s quail when numbers are good, a flushing dog might do too well because sometimes after you’ve broken up the covey, the singles might let you walk right by them or they’ll let you walk right by them and then flush out the back door and when you go, it’s more difficult to turn and whirl around and shoot 180 degrees behind you. And so, now in that situation might help push the birds out in front of you and there, there wouldn’t be the issue with the tree cover within Gambel quail habitat in general. Of the three species, it might be best if you’re going to hunt with a flushing dog to stick to Gambel quail.

Hank Shaw:

Got it.

Kirby Bristow:

Scaled quail runs so much that a big heavy Lab might not be able to stay up with him, like you might wear him out before you get to the birds holding tight on scaled quail.

Hank Shaw:

You’ve already mentioned that hunting Mearns quail without a dog is pretty much a fool’s errand. Can you hunt either the others without a dog?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah. Actually people do pretty well hunting Gambel quail without a dog and you could probably do well hunting scale quail without a dog. Depending on your thoughts on fair chase, if you’re willing to shoot birds off the ground, you can get a lot of shooting opportunities on scale quail, because sometimes they exist in fairly open areas with very little cover [crosstalk 00:53:04].

Hank Shaw:

That is exactly how I shot my first scaled quail in Texas where I was going after him then like, “Well, shit, they’re not going to fly.”

Kirby Bristow:

Right, right. If you’re going to run like a rabbit, you’re going to die like a rabbit.

Hank Shaw:

Pretty much.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, I have to admit I’ve done it out of frustration myself, but yeah, so if you don’t have a dog that can be a very productive way to take both Gambel quail and scaled quail.

Hank Shaw:

Got you.

Kirby Bristow:

And finding the coveys because they call is a little easier without a dog. I mean, it’s not easier without a dog, but it can be done without a dog whereas Mearns quail, you’re going to walk past coveys that you never knew were there if you don’t have a dog.

Hank Shaw:

So, you had mentioned the kind of rough grouse effect with hunting Mearns quail, that’s why I typically will hunt with a 20-gauge, but I like to hunting with either lead sixes or like business sixes because I know they’re not really stout birds, but I want to be able to shoot through twigs and branches to get to that quail whereas I might shoot seven and a half steel or seven steel with the other two species of quail.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, I will use the shoot seven and a half lead on everything, but there are times if Gambel quail numbers are low, the majority of the birds that you’re shooting are adults and they tend to, like we talked about earlier, flush wild and so you might have longer shots and some of those situations though, I’ll use sixes, but on Mearns quail when you’re shooting through the trees like that, I really hadn’t thought about using a bigger shot, like that might help. A lot of times, I’ll swing and shoot at a bird and think it felt right, but not even see it get hit, and then go over and the dog will find it or sometimes you’ll listen and you’ll hear a thump on the ground and that will be your indication that you actually hit the bird, so maybe-

Hank Shaw:

That’s also grouse effect.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah. Maybe a heavier shot would be better in that situation. The other thing about Mearns quail is it’s a covey rise, opposite of what I was talking about with Gambel quail where you want to mark the covey down and go hunt the singles. Mearns quail, because you’re entirely dependent on that dog to find them when they flush, they fly often through trees, so you can’t really mark them down well. And then one bird stinks less than 10 birds, so the chance that you’ll get a point on a single is less than a point over the covey. And almost all of the coveys are over point. So, I always advise people to empty your gun on that covey rise, because there’s no guarantee that you’re going to find any of the singles.

Hank Shaw:

Got you. It might also be that might be your time to switch to the auto loader, like a 28- or 16- or 20-gauge auto loader for Mearns as opposed to the classic side by side or over and under.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. I always hunt with an over and under just because I shoot it well, but I remember one year, there was a long time when we just for simplification of regulations, we had a three-shell limit on all of the shotgun hunting. And about 15 years ago, I guess, we changed it to allow more than three shells for upland birds. And I thought, “Well, I’ll give that a try.” And I took the plug out of my model 12 pump gun and it was a good year for Mearns quail and my nephew and I waded into a covey. And we had five dead birds on the ground before we retrieved any of them.

Hank Shaw:

Jeez.

Kirby Bristow:

And I thought, “Maybe this isn’t such a good idea. We can’t keep track of where they’ve all fallen if you hunt without a plug,” but yeah, that would certainly address the issue of standing there with an empty gun when the easy birds flush.

Hank Shaw:

Right. If you were to tell a guy where and when to hunt these species of birds, what would you tell someone, who will say like they lived in, I don’t know, Wisconsin or Minnesota, who wants to hunt these desert birds and they wanted to make a trip out of it. When and where would you tell them to go? I’m not asking for like an X or something, but like we’ve already discussed that, that Mearns are in the south and typically southeast, so we’ve got a general idea of it but flying to Phoenix in January or something like that.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, I would suggest January is a good month for all three. The season opens in October, but it’s darn hot in Arizona in October. And so, especially if you’re hunting with a dog, they tend to do much better at finding birds when it’s cooler and wetter and that doesn’t happen until after Christmas in Arizona generally. And so, that would be the time to come if you want to hunt all three. Now, with Mearns quail, like I said earlier, the popular hunting areas can get hit pretty harder in the season. And so, if you want to hunt those areas, you might have to come out for the opening weekend.

Hank Shaw:

Is that November or is it October?

Kirby Bristow:

The opening weekend for Mearns quail is in December. They breed later. They’re breeding in July and raising broods in August and September, so to prevent hunting birds that are just barely able to fly, we have a later season opening for Mearns quail.

Hank Shaw:

That makes sense. It’s like I’ve hunted a dozen Yuma, and if you hunt a dozen Yuma in the opener, you can have like 36-day-old doves, which is a little weird.

Kirby Bristow:

Right. Yeah, yeah. Yeah, so for that reason, we have the later opener for Mearns quail. The other thing is, at that time, and this is not the reason for the season, but it’s finally cool and wet enough that dogs can do well finding birds after December and so, that’s a better time to try and come to Arizona to hunt quail. The problem is trying to get here for the Mearns quail opener is they’re depending on these summer rains, which can be more spotty or in Arizona winter, winter rains come across the entire state in these big fronts that generally soak a bigger part of the state.

The summer rains, they occur in these isolated thunderstorms and so, unless you’re paying pretty close attention to the rainfall, you might hunt a mountain range that did poorly. You can have a mountain range that does well right next to a mountain range that did poorly in terms of summer rains. In the very good years, the very good summers, all the mountain ranges get rain, but in more of an average year, you can have that spotty distribution of rain. And so, it often helps to wait a little bit and get some recent intel on where the best hunting is. And so sometimes I tell people, when they’re asking to come hunt with me, I’ll tell them, “Don’t come until January I’ll have it figured out by then.”

Hank Shaw:

Got you. So, for gear other than guns and ammunition, for Gambel’s, I’m typically wearing, like I have a pair of Filson chaps that I wear because it’s just so, there’s sticker bushes everywhere. And I love it when it’s actually cool and then I’ll wear a tin cloth jacket, but that gets super hot if you’re hunting the afternoon. I think that the best advice that I can give to a listener and I want to hear yours as well is if you’re hunting Gambels, there’s going to be cactus and cholla and things with thorns everywhere, cat’s claws and such, so you need some scratch-resistant stuff, no matter what it is.

You also need good boots for all three of these species because you’re going to be walking for quite a while. I wear thin Merino wool underwear and I wear Merino wool socks, because cotton chafes, nobody likes that. I mean, I typically walk six, sometimes 10 miles and in any given day to try, and I will say this. I’ve only limited on Gambel’s quail exactly once and I’ve limited on Mearns quail a fair number of times, but it’s a much smaller number, but if you want to put a bunch of birds in the bag, you will be walking for quite a while, so be prepared for that. So, I’d be interested to hear what’s your setup? What your gear that you take the field in?

Kirby Bristow:

Much like you described a good comfortable pair of boots because you will be walking along ways. And if your boots are tight fitting or have a hot spot when you’re testing them out in the store, they’re going to be brutal in the fields, so you got to make sure you got boots that won’t give you blisters.

As far as the gun, I carry a light gun like most upland bird hunters because I’m going to be carrying it all day and they’re fast. You want something that comes to the shoulder real quick. For as far as chokes for Mearns quail, I use the most open chokes, I have skeet and improve cylinders, generally is what I do. For Gambel quails and scaled quail, a modified choke is probably better. As far as gear, I always wear, like Carhartt pants that are fairly thick because for any of the species you can run into some pretty thorny stuff. It’s not quite as big a problem for Mearns quail, but they do occur in some pretty dense cat claw country, which can rip your regular Levi’s to shreds.

And then yeah, it depends on the temperature. I’ll often start out with a jacket that I shove inside my vest after an hour of hike and if it’s really cold, but yeah, in Arizona, you can pretty much count on it getting to be a T-shirt weather at some point during the day. And I carry a Leatherman or a multi-tool in my pocket for removing cactus for my dogs. Some places I’ll put boots on the dogs. Usually that’s more of like there’s some country in the southeast part of the state where I hunt scaled quail, but it’s volcanic rock, and that will wear their pads out real quick. But as far as cactus, I usually don’t. I just hunt with dogs that are used to cactus and have learned how to avoid it. Of course there’s some places where he just can’t avoid it, so I just try not to hurt in those areas.

Hank Shaw:

I know. I saw [inaudible 01:05:01] Pudelpointer or Shiloh completely covered in cholla running out of a Gambel’s quail spot and everyone was like, “No.” Our dog had like 12 cholla things sticking to her.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. And then as far as prickly pear cactus, that’s usually not a problem. And in fact, when Gambel quail hunting is good, you end up kicking a lot of cactus.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah. I asked Ron Schara from the flush about that. He kicked a barrel cactus and got one right through his boot.

Kirby Bristow:

That would be bad.

Hank Shaw:

It was bad. So, let’s talk about eating for a second. Now I have eaten every species of quail under the, well not under the sun, but in North America. And I haven’t noticed a huge difference in flavor between from species to species. My mind wants to say that Mearns, quail tastes the best, it could just be because they tend to be a little bigger, but I pluck virtually all of my quail unless they’ve been blown to pieces. I figured they’re worth it and so I get that full skin and fat flavor that goes with the rest of the meat. And I find them all kind of universally delicious with the scaled quail being slightly stronger in flavor than the rest, but still pretty mild in the grand scheme of things and I’d be interested to hear your thoughts.

Kirby Bristow:

I think I would agree. I tend to think of Mearns quail as being the best. And it may be because you don’t often have to work harder to get them or maybe they are more plumped and heavy. They’re the heaviest of the three quail even though they look small because they have such a short tail. They look small, but weight-wise, they’re a bit bigger than the other two species.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, they’re like little tennis balls.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. But yeah, I haven’t really noticed the difference between scaled quail and Gambel quail in terms of taste. I don’t tend to pluck birds, but-

Hank Shaw:

Blasphemy.

Kirby Bristow:

I don’t. I always say all quail are delicious and I always say, most of the dove and duck recipes that I’m familiar with that are reported to be good usually involve a very involved process of disguising the flavor. And I always say you could cook a quail with a Bic lighter, and it would be delicious. You don’t have to work at it to make them tasty.

Hank Shaw:

Well, you don’t have to work about, for most birds, to make them tasty. I mean, it’s if you’re talking to a guy who does this for a living. And I think one thing that I have found that has been very, very rewarding about, not only the quail hunting in Arizona, but the quail eating in Arizona, is the sheer just vast array of edible wild plants that not only do they eat, but they live around. So, I mean, if you know what you’re looking at, you can get fat in the Sonoran Desert. Pretty much everything in the Sonoran Desert is edible. I mean, there’s ironwood seeds, there’s Palo Verde seeds, there’s mesquite, there’s prickly pear, both the paddles and the fruit. There’s cholla buds. There’s wolfberries.

I mean, I can go on and on and on about the edible plants that live in and around where you’re hunting these birds. I mean, hell, the Mearns quail live around Emory oaks and Emory oaks are the only acorn in North America that you can eat just by roasting. Every other acorn in North America, you have to leech out tannins and while Emery oaks have tannins, but they’re in such low levels that you can buy a bag of acorns from the Apaches or the tunnel autumn or whoever, and they’re just roasted, you can just sit there and eat them and that’s unique to North America.

So, the culinary opportunities, I have a recipe on the website for a prickly pear barbecue sauce that I do with them and the synergy between region because you’ve got the Sonoran desert and all of the food that is native to the Sonoran Desert, you’ve got the wild food that is native to the Sonoran Desert to work with and even the Mojave Desert has a fair number of good things to eat in it that the far more than say spruce grouse or sage grouse or some of the other birds and animals that I hunt, the mind can go in any number of directions with these birds because not only are they delicious with a glider, just like you said, but you can pair them with the environment in which they live and create a very special and a memorable meal.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, I wish I knew more about that subject and I am always interested in hearing stories of people that have done that, but I’m just not the chef that you are or that others who pursue these birds are.

Hank Shaw:

Well, we’re going to have to hunt together.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, well, you’re going to tell me your recipes. I mean, if I had to share my recipes, it would be more blasphemy like you had mentioned.

Hank Shaw:

I mean, I will say one thing about simple recipes for quail that is fairly unique to the wild world is along with cottontail rabbits, they’re one of the very few birds that you can chicken fry. Quail live fast and die hard, so you’re not likely to have a three-year-old quail in the bag. And so, that gives you the ability to fry it. And it’s delicious. Buttermilk fried quail is fantastic.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, I hunted in Texas with the guy, who that’s how he cooked them all.

Hank Shaw:

And plucked or not plucked, they’re good either way. So, we have been going for a bit. I would ask you, have we missed anything? Is there some aspect of what we’re talking about that you’ve been dying to say that I have failed to bring up?

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, I think we’ve pretty much covered it. I got lots of bird-dog stories.

Hank Shaw:

Well, tell me. Let’s finish with a good bird dog story.

Kirby Bristow:

I shot a bird. She went to retrieve it. She comes walking back to me, gets within about 10 feet of me and I can see that the bird in her mouth is still alive because he’s got his head up and she locks up on point, and for a brief moment, I thought, “If the bird that she’s pointing flushes, I won’t be able to stop myself from shooting at it.” And I imagined that she’s going to drop that bird in her mouth and the way it’s got his head up, I’m afraid it’s going to run off.

And so, all of this crossed my mind over a split second. And the bird she’s pointing flushed, and I shot it and she dropped the one in her mouth. And luckily, it didn’t run off and I got it all back. But yeah, that was one of those moments that you think, “Uh-oh, what do I do here?”

Hank Shaw:

It’s kind of a double or nothing deal.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. And it all worked out. Another time, I had a dog that liked to carry the bird. Sometimes they’re proud of their retrieves and they don’t want to run straight back to you with it. They want to walk a big circle around you and make sure that you know that that’s their bird, and then they come in. And so, she was doing this and I knew that there were some singles or I had assumed that there were some singles in the area. This was a Mearns quail, by the way. And I’m wanting to get that bird in hand, so that I’ll be ready if another bird fleshes and so, I yelled at her and she dropped that bird while it was still alive and it took off running and it’s hopping around in this bunch grass that’s knee high.

And so, I set my gun down and I’m trying to catch this bird and in the process, I flushed the single one and at first I thought it might have been the bird that she just retrieved, but then, I did finally catch the bird that she had in her mouth, but yeah.

Hank Shaw:

Cue Benny Hill music.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah.

Hank Shaw:

My only funny Arizona quail hunting story is I was Gambel’s quail hunting in some, I mean, you imagine if you’re listening out there, picture the Arizona desert and all of the thorny things in it, that’s where I’m hunting. So these birds get up and I shoot one on the covey rise and it sails dead into a prickly pear and gets impaled on the prickly pear. Like I had to pull the quail off of the prickly pear thorns, like “Wow.” That’s like a horror movie ending for that poor.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, yeah. And I don’t understand how they avoid it because I’ve seen them land in prickly pear and cholla cactus. You see them land near it or in it and you think how do they avoid getting stuck? But yeah, a dead bird like that would have not been able to avoid it.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah, it was pretty grim.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah, one piece of gear I often thought you should have for Gambel quail hunting is a shotgun, but that has a shovel that folds out when they run down a packrat hole.

Hank Shaw:

I’ve never seen that.

Kirby Bristow:

[crosstalk 01:15:07]. Many times they hit the ground running and they go down a woodrat den and some dogs will dig him out, but it takes a pretty bold dog to do that. And I’ve always made every effort to retrieve them when I can, but often it ends up with a long involved process of tearing that packrat den apart to get them. I’ve had them get out, get away from me when I tried that, too. Yeah, so if you could just have a shovel that folds up and of course, you’d want to unload the gun first.

Hank Shaw:

That’s for sure.

Kirby Bristow:

But yeah, the Mearns quail tend to hit the ground and just stay where they’re hit even if they’re wounded. Sometimes, they’ll run on you, but boy, Gambel quail and scaled quail if they’re not dead, they will hit the ground and run off and run down holes, they’re tough.

Hank Shaw:

Yeah. I mean, they’re like micro pheasants.

Kirby Bristow:

Yeah. Yep.

Hank Shaw:

Well, this has been great, Kirby. If somebody wanted to get a hold of you, how would they do that if they wanted to talk about quail in Arizona?

Kirby Bristow:

Probably the best way would be to send an email to my game and fish email, which is kbristow, B-R-I-S-T-O-W, @azgfd.gov. Yeah, if they send me an email, I can give them any information they want or if I can even make it happen, I might even sneak out and go hunting with you some time.

Hank Shaw:

Very cool. I definitely hope to get in touch with you this winter. I have tentative plans to be in Arizona to chase random tasty animals in January, if not early February, but probably January. And I will definitely let you know and we should definitely-

Kirby Bristow:

Gambel quail fits the random tasty animal description.

Hank Shaw:

Yes, Gambel’s quail definitely fits the random tasty animal description. All right, thanks for being on the show and I will talk to you soon.

Kirby Bristow:

Thank you, Hank.