As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

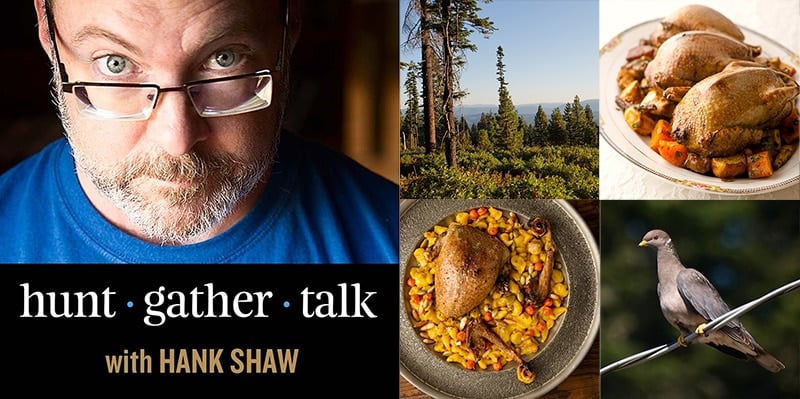

In this episode of the podcast, we’re talking about band-tailed pigeons with biologist Mark Seamans of the US Fish & Wildlife Service. Seamans is a fellow bird hunter and oversees management of non-waterfowl migratory birds in the West, and that includes the band-tailed pigeon.

Every episode of Hunt Gather Talk digs deep into the life, habits, hunting, lore, myth and of course prepping and cooking of a particular animal. Expect episodes on pheasants, rabbits, every species of quail, every species of grouse, wild turkeys, rails, woodcock, pigeons and doves, and huns. Thanks go out to Filson and Hunt to Eat for sponsoring the show!

Band-tailed pigeons are an obsession of mine. Even though the limit is only 2 per day and the season only nine days long, I make a point to hunt them every year if I can. They are our last huntable native pigeon, and hunting them puts you into the High Sierra in fall, a gorgeous time of year to hunt a gorgeous bird that is a trophy at the table.

For more information on these topics, here are some helpful links:

- I wrote an essay called In Defense of the Pigeon, which extolls the thrill and virtue im chasing and enjoying all species of pigeon.

- A cool web page all about band-tailed pigeons, from Cornell University.

- An article on hunting band-tailed pigeons from Project Upland.

- By far the best book written about band-tailed pigeons, Worth Matthewson’s Band-Tailed Pigeons: Wilderness Bird at Risk

- All about the single-leafed pinon pine, a favorite food of the band-tailed pigeon.

- An article about pigeon milk, which parents give to their chicks.

Recipes

- You can find all my pigeon and dove recipes here.

- But start with simple roast pigeon.

A Request

I am bringing back Hunt Gather Talk with the hopes that your generosity can help keep it going season after season. Think of this like public radio, only with hunting and fishing and wild food and stuff. No, this won’t be a “pay-to-play” podcast, so you don’t necessarily have to chip in. But I am asking you to consider it. Every little bit helps to pay for editing, servers, and, frankly to keep the lights on here. Thanks in advance for whatever you can contribute!

Subscribe

You can find an archive of all my episodes here, and you can subscribe to the podcast here via RSS.

Subscribe via iTunes and Stitcher here.

Transcript

As a service to those with hearing issues, or for anyone who would rather read our conversation than hear it, here is the transcript of the show. Enjoy!

Hank: Hey, Mark, welcome to the Hunt Gather Talk Podcast. I’m glad to have you on.

Mark Seamans: Thanks, Hank. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Hank: So today we’re going to be talking all about one of the more obscure game birds in North America, the band-tailed pigeon. It’s a creature of the West, and if you’re listening to this anywhere East of the Colorado Rockies chances are you may not even know that this bird exists. We’re going to fix that problem today. Mark is a biologist with U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife. So introduce yourself, and tell people a little bit about your biology background, and your familiarity with the pigeons, and what you hunt, and all that kind of good stuff.

Mark Seamans: Yeah. It goes back a ways. I was born in Oklahoma, but mostly raised in your neck of the woods, Northern California, where I was quite the fisherman, and seldom the hunter, but it seemed like when I did hunt when I was of age I got to go hunting with my dad and his three brothers. I don’t remember much about the hunting, but I remember hanging out with them, and that was always such a treat for me. I grew up fishing, but also hunting to a small degree, and just thinking about it as a well-rounded activity not just hunting, but socializing with family, and I still do that to this day.

One of my main pursuits these days is deer hunting. I’m in Colorado right now. It’s where I’m stationed, so there’s ample opportunity for things like elk, which I’ve hunted, of course, antelope, and deer. I just like mule deer hunting. Besides that I like to bird hunt early in the year. I have a dog. I use her sometimes, not others. Mostly grouse. I try for the duskies here and the ptarmigan mostly just things I can drive to in a day hunt from my house. And occasionally I’ll go over to Nebraska or Kansas and hunt some pheasants later in the year.

Hank: Yeah, you got chickens out there, too.

Mark Seamans: Yes, and I was in that region last year, and I decided I was hunting quail.

Hank: Well, yeah, I mean, that’s the coolest thing about Western Kansas, especially. You can get all three. You can get pheasants, prairie chickens, and quail in the same day if you know where to go.

Mark Seamans: Yes, I saw pheasants and the quail I was in Southeast Colorado, actually, and the prairie chickens were there I just did not see them, but, anyway, my background when I graduated high school it’s been a while. Guidance counselors, I think, were present, but I don’t recall that. I just started to work, and I went to college part-time thinking I’ll figure something out, and got into biology. Started taking biology classes, and realized pretty quickly through some contacts that you can have a career as a wildlife biologist.

To me, that was shocking. And it took four or five years to actually figure out what that meant. I thought it meant working on a refuge possibly, or law enforcement, but as I went along and started gaining more knowledge, and more interest in the field it became apparent to me you could really do some neat science in the field. There’s a lot of people, a lot of top-notch scientists that have worked and are working in the field of wildlife biology, so I kept pursing my college career, if you will. At the same time I was working and doing research, and I got a bachelor’s degree in biology, a master’s in wildlife biology at Humboldt State.

Hank: Of course, everybody either goes to Davis or Humboldt, especially, out here. There’s a big rivalry between the two schools.

Mark Seamans: Yeah, early on I got into Davis. I was at Sac State when I started, and that’s where I got my bachelor’s degree. And once I figured out what I wanted to do I applied for Davis. I got in, but I had made friends at Sac State, so in hindsight it wasn’t the greatest career move. Davis has a better program in the field, but that’s what I did. I ended up at Humboldt after that, got my master’s there. And then I ended up at the University of Minnesota where I got a PhD.

Hank: Is that where you met Rocky?

Mark Seamans: I met Rocky at Humboldt.

Hank: At Humboldt, okay.

Mark Seamans: He was at Humboldt. Rocky Gutiérrez was my professor there, and at Minnesota.

Hank: Very cool. We’re going to be talking to Rocky Gutiérrez in this podcast, and we’re going to focus primarily on mountain quail, and we may bleed into a little bit of valley quail, too, because that guy is the guru of game birds.

Mark Seamans: He is one of the true experts that we have in this country without a doubt, and it’s far-reaching. I mean, he’s studied every upland game bird, I think. His master’s was on band-tailed pigeons.

Hank: Yeah, I know. I was talking to him about this, and he’s like, “Well, you should have me on as well.” Like, “I can’t have you on every episode.”

Mark Seamans: Oh, that would have been fun. He and I are really good friends. Actually, a sidebar, we had him deputized and he officiated our wedding, my wife and I.

Hank: I’ll be damned.

Mark Seamans: Yeah.

Hank: So what did you do your research in graduate school because usually people focus on birds, or whatever it is?

Mark Seamans: Well, when I went to graduate school another thing that surprised me was somebody might actually pay you to go to graduate school instead of you having to pay tuition. Now that got covered in a small stipend. And what was available to me at the time was studying spotted owls occurs in the same areas band-tailed pigeons occur as it turns out.

Hank: They do. They’re not as delicious as band-tailed pigeons, though.

Mark Seamans: I can’t say I’ve ever tried one, but it provided me a great opportunity to live in the field for about six months a year which was outstanding in some of the Western states, but more than that what it really put me in touch with was a lot of scientists who do a lot of quantitative research as it turns out. So I gained a lot of expertise, if you will, at the time in how to estimate things like population numbers, annual survival rates, reproductive rates, things like that.

I didn’t totally see it at the time when I was doing it all, but as it turned out once I had got my PhD there was quite a few jobs that were open to me that were really appealing. Some of them in academia, and I thought about that, but also with the USGS which does a lot of research, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. And, really, the first job I got offered was with the Fish and Wildlife Service and I took it. It was just right down my ally. It was a lot of quantitative stuff, but also working nationally and internationally, and designing studies for wildlife. And I was hired in the migratory bird program back East, so it was working on migratory birds.

Hank: That’s right. You, like a previous guest of mine, Owen Fitzsimmons, I love this term a webless specialist, right? Which is the birds that fly up and down Canada, United States, and Mexico that aren’t ducks and geese.

Mark Seamans: Correct, and some point of confusion there I think with some people who actually think about migratory webless game birds it also includes marsh birds, the Rallidae.

Hank: Let me stop you for a second.

Mark Seamans: Sure.

Hank: So there’s this big rumor that if you talk to duck hunters that everybody’s seen coots fly, right? And coots can’t fly worth a dam when they’re trying to get up off the water, but everybody will say, well, yeah, they migrate at night at 30,000 feet so once they get up they’re pretty impressive. So is that true or not?

Mark Seamans: That I don’t know. That sounds awful high.

Hank: I know.

Mark Seamans: I don’t know abut that. That one I hadn’t heard of. I am far from a coot expert.

Hank: Oh, yeah. I need to get Ariel Fournier back, and she’s a rail expert. I know they migrate at night, and they apparently migrate super high up, so that’s why nobody ever sees them migrate.

Mark Seamans: Pretty much all rails do, or they’re believed to. A lot of new information is coming to light on bird migration, especially, the height of migrations in general just because we now have such technology and radar that you can detect migration flocks of birds. We can’t necessarily pull a species apart, but we’re finding out all sorts of new stuff with how far they migrate, and how high.

Hank: Well, to 30,000 foot just for a second. So one of the things I wanted to explain to listeners is that scientists like you, and virtually almost everybody that I’m having on this podcast because I want to make this a science heavy kind of season is, correct me if I’m wrong, but much of what fish and wildlife, and the local fish and game agencies, and USGS, you’re trying to get more data on the game species and their associate. For example, if you did waterfowl you’d also probably end up looking at the other webbed migrators as well. To give really all of us an opportunity to know, okay, well, what is the status of the species? What’s the habitat like? Is everything around? Are the populations increasing or decreasing. That translates to most of the listeners of this podcast to can you hunt them or not? And does the bag limit go up or down, or does the season go up or down? So this is that science and scientists like yourself are underpinning most of the seasons in the United States, right?

Mark Seamans: Correct. There’s a distinction at least for me, of course, with migratory birds and nonmigratory birds. So, of course, your nonmigratory birds are more your quail, turkeys, grouse, those kind of things. I don’t deal with those. We deal with things that essentially migrate across state lines that’s why it’s been deemed a federal responsibility. So the nonmigratory birds individual states handle those. They handle their own seasons, right? So California doesn’t have to look like Oregon, doesn’t have to look like Nevada for the nonmigratory piece. For the migratory birds there’s a large framework in place about how we develop harvest management plans. That’s generally what we call them, or strategies.

It’s a definite partnership between the federal and state governments via what we call the flyway system which most hunters I’m sure have heard of migratory flyways. There’s four of them in the country. Birds tend to stick to those where they breed and where they winter, but, anyway, there’s states within each one, of course, and there’s councils within each flyway. And so we work with those councils to develop harvest strategies, and develop a system where we propagate regulations every year. And so in the Pacific flyway where you are you’ve got the coastal states, Nevada, Arizona, and so forth, Idaho, Utah, their regulations for a bird that might occur across those states is going to look pretty similar. That’s what we call the framework for band-tailed pigeons. It’s only three states in the Pacific, but they have the same number of days, daily bag limit, and so forth that you can hunt every year.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Historically when you look at regulations it wasn’t always that way. I don’t know why. I’ve tried to figure out some of this stuff that happened in the ’30s and ’40s. Why did Washington have a closed season, but the other states didn’t for band-tails? Stuff like that. It’s not always clear to me why that happened, but these days usually within a flyway for an individual species even waterfowl, too, regs are usually more uniform. They’re not perfect, but they’re close.

Hank: In theory, if the same population of doves, or band-tails, or whatever, moves through these states so that if you have a massive bag limit say in one state, but not another you could really put the wood to a species on its way through, or where it winters, or where it spends other parts of time, and then you can really do damage to an overall population because it’s not only in your one state.

Mark Seamans: Yes, and there’s obviously some species you want to divide up even within the Pacific flyway different cackling geese, and so forth, but with most species band-tailed pigeons, for example, what we’re talking about we generally consider the band-tailed pigeons in the Pacific flyway is coming from one population. We’re managing that entire population. We don’t want local populations of band-tails to go extinct, so we watch for that, but in general we don’t set regulations for that because hunting tends to get dispersed, and these days it seems like harvest seems to be more spread out than it was historically that maybe something we’ll talk about with band-tails because that definitely was not the case at one point in time.

Hank: So there’s two flyways of band-tails, right? Are they actually in what is it the central flyway?

Mark Seamans: Yes.

Hank: Okay, so it’s officially the central flyway, but we really think of it like the birds that go from British Columbia to Baja and then there’s a bunch of birds that go from Idaho to probably Sonora, and there are two parallel lines. Do they ever mix?

Mark Seamans: Yes.

Hank: They do?

Mark Seamans: They do. So as you touched on some people think there’s subspecies. They have been identified as two different subspecies. They’re the same species just they look a little different.

Hank: Do they?

Mark Seamans: A little different size. The ones in the interior, what we’ll call the interior, are slightly smaller, a little paler, I believe, grayer, but hard to tell apart unless you were to see them side-by-side I imagine, which I don’t think people do, but they do intermix. So to back up a step we said that the coastal population is the coastal states runs from British Columbia down through the coastal states into Baja, whereas, the interior populations, also called the Four Corners population because it’s roughly centered around the Four Corners states of Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado, and then into the highlands of Mexico.

Hank: Gotcha.

Mark Seamans: And they do intermix. There’s historical banding studies where people have banded tens of thousands of these things in both flyways. Sometimes, very rarely, you pick up a banded bird that crossed over.

Hank: Well, give me an idea about this migration. So if you’re Mr. Band-tailed pigeon what does your year look like? Because everybody, I think can put in their head what ducks do. So they fly South for the winter, and fly North for the summer, so what is a band-tailed doing during its year? Because I know here in California you’ve got this Northern zone and Southern zone which doesn’t really make a lot of sense because it’s not really northern and not really southern, but it’s geared towards where the pigeons are in their annual cycle. So walk me through them from I don’t know spring through the following spring.

Mark Seamans: Sure, so band-tails, I’d say generally because there’s some big exceptions, but they generally follow that same pattern that ducks do. So in the spring as early as March maybe even a little earlier band-tails start migrating North. So in the Pacific flyway where you are they will generally winter from the mid point of California South, okay? So most of the band-tails from British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, Northern California are going to move South. In the summer they start nesting. They can start nesting early. Band-tail is a unique bird in that there’s been documented nesting I think in every month of the year.

Hank: Huh.

Mark Seamans: And it’s really tied to food availability people think. They’re going to migrate out of the northern states of Colorado and Utah in the winter because it’s just not hospitable there for them, but in the southern states they might winter in Southern New Mexico, Arizona. They winter in Southern California. If there’s food availability especially as they get into Mexico they’ve been known to nest not in great numbers, but they will continue to nest year-round, but in general it’s just like waterfowl they push North in the spring. They start nesting. They nest a little bit later. Their peak nesting is somewhere around July in the Pacific flyway and in the Rocky Mountains we think. They fledge their young. They can nest two or three times a year we think.

It’s hard to track these things out in the wild, but we think they can nest up to two or three times, and, again, it’s probably food dependent. And then as you get into the fall they start moving back South. However, it’s been noted multiple times that you can have them winter essentially in British Columbia, or further north in the interior population, and it’s generally believed that’s just a complete function of food availability. If something, a big berry crop, acorn crop, something is available to them maybe they don’t feel they need to leave, or leave as early. It can be variable.

Hank: Interesting. In most Columbidae, so most of the pigeon and dove species they don’t really like cold weather because they don’t have down, or anything like that, so how do they manage winter in British Columbia, or are they really right on the coast where it’s cold and steady, but not too bad?

Mark Seamans: Yeah, even as you move north they’re more of a lower mountain elevation bird. So I would assume those records they’re from a while ago where they’re wintering. They were noted wintering around British Columbia. There’s coastal, so temperature is somewhat ameliorated, but these pigeons from what I understand they really like to focus on the available food source, and make use of it whether it’s madrone, or pinyon pine, or acorns, and they can focus on that, but they can focus on bird feeders, too.

Hank: Yeah, I know.

Mark Seamans: They can go just on crops. They show up in a lot of different places. And there was concern about crop depredation at one time, although that’s generally gone away. So I think the migration patterns, and the breeding patterns to some extent, too, are tied to that food availability.

Hank: Okay. So let’s get into that. Let’s talk about that. If I’m a band-tailed pigeon what are my favorite things to eat, or does it change throughout the year?

Mark Seamans: Well, it does change because what you may find on their summer grounds may not be available on their wintering grounds, but, again, it’s what’s available, so in the breeding range in the North when I’ve seen them they’re eating a lot of berries. Huckleberries, what is it? Cascara berries.

Hank: Oh, yeah, that’s California coffeeberry is one version of that.

Mark Seamans: Yeah, but any berries they can really get their feet on. If you move South they also like hardwood forests, especially oak forests. So they’re big on mast, madrone, acorns especially. So as you move South, especially into California, and Oregon, too, in the Willamette Valley, and so forth, you have some massive acorn and oak forests, so they’ll take advantage of those, too, especially as they move South.

Hank: I’ll put a picture of it in the show notes, but a valley oak acorn can be two inches long. I mean, obviously, not every acorn is going to be that big. Band-tails, they’re a big pigeon, but they’re still a pigeon. It’s a large mouthful for a pigeon, no?

Mark Seamans: It is surprising, and it’s always been noted it looks like they got a small mouth so they may be a big, study pigeon, but their mouth doesn’t look that big, but somehow they do get those acorns in, and like almost all birds they have a crop. Think of it as a pre-stomach where they can store food, and help partially digest it. And the band-tail is pretty good at that from what we know as far as the acorns. They’ve got a shell on them, so I think it’s the crop work within the band-tailed pigeon itself that helps break down that acorn before it passes onto the stomach in the band-tail.

Hank: Interesting. I know they like pinyon pines, too, because one of the spots where I can hunt them, well, right now, I mean, this is sort of a weird moment in time for us in California because our national forests are temporarily shut down because of fire danger, but normally I can hunt them in the Toiyabe National Forest where they really, really, really like pinyon pines.

Mark Seamans: Yes, and, especially the Four Corners that interior population as you can imagine has a lot of opportunity to feed on pinyons, and they do. And, again, that’s if you’ve pulled pinyon pine seeds out of a pinyon pine cone you know they have a pretty thick little husk on them, too, or shell, and, again, that’s probably the work of the crop that helps them digest that.

Hank: Gotcha. I guess they probably switch to bugs in the springtime because the chicks need the protein, and the hens need to recover after laying so many eggs.

Mark Seamans: Probably true. I don’t know that we know completely how they make use of insects, but most, especially, the game birds that I’m familiar with as in the ground game birds, the grouse, the quail, I mean, a lot of them do focus on insects early on, and part of it is that protein requirement.

Hank: So this is a unique bird in the sense of most of the birds we hunt and you just alluded to that are ground birds. And most of them give birth to precocious young which means they’re little balls of fluff that can go feed themselves. All the ducks, all the geese, all of the gallinaceous birds they hatch, and then they’re being led around to eat yummy things by their mom, but they’re not being fed by their mom. All the doves and pigeons are different though, so the doves and pigeons have to be fed by their parents, right?

Mark Seamans: Correct. They’re what’s called altricial so meaning they’re born not able to feed themselves, to fend themselves, so forth, so they’re completely reliant on the adults, and the band-tails both adults takes turns actually incubating eggs, and feeding young, but that crop comes into play again, of course, because they produce something called milk.

Hank: Pigeon milk.

Mark Seamans: Pigeon milk.

Hank: Yeah, I heard about this. What is that?

Mark Seamans: It’s an oily crud looking stuff I think. I’ve seen a little bit in other doves, but it’s produced from glands in the crop, and it’s partially from what’s in the crop, but mostly it’s produced from the epithelial lining I believe within the crop. And this is what they feed pigeons for their first I don’t remember week or so of their life, and they wean it off of them pretty quick, but that’s what the young first get is this stuff called pigeon milk that’s produced by the adults.

Hank: That’s so weird.

Mark Seamans: It is.

Hank: I’ll see if I can post a link to a video of pigeon milk. If you watch nature shows you’ve seen adult birds feed their baby birds, and it’s usually pretty gnarly, but pigeon milk is especially gnarly.

Mark Seamans: It is, and later on in the breeding cycle young still in the nest are just out they’re regurgitating whole foods, or more whole foods from their crop.

Hank: Right.

Mark Seamans: As the young are getting older, so the crop also functions as a storage device for the birds.

Hank: So one major thing about band-tailed pigeons if you’re familiar with this bird at all out there you know that it’s, A, a native pigeon. It’s native to this part of the world. B, it is a big pigeon. It’s bigger than the typical neighborhood pigeon, the Columbia Livia, the rock dove. The thing about pigeons versus doves is that they are larger, they’re smarter, they’re tougher, they live longer, and they have fewer young.

You mentioned that they can nest two to three times as year, which is good, I hadn’t known that, but unlike doves of which there’s bajillions of there’s not a lot of band-tailed pigeons because they don’t raise a ton of eggs at a shot so that they rely more on more of their chicks actually becoming full-grown pigeons than doves do, or the dove method is kind of like we’re going to nest and have 80 trillion chicks, and some of them are going to survive. Whereas, the pigeons are going to be more like, well, we have two, and we want to make sure that both of them survive, but from a hunter’s perspective, correct me if I’m wrong, this is why you can’t kill 10 band-tailed pigeons a day because their recruitment is not nearly as dramatic as it would be if you were a dove.

Mark Seamans: Well, correct, and even for band-tails it’s even a little bit more tough than you described because they typically produce one egg from what little we know. It’s really, really difficult to find their nests, and I really applaud researchers who have found multiple band-tailed pigeon nests because that is hard.

Hank: Aren’t they way the hell up in trees?

Mark Seamans: They can be. In the Pacific they like to nest in the conifers, also the hardwoods, too, but they can be up to 60, 70, 80 feet, or even higher, but they typically are below 60, I believe, but they usually produce one egg 10% of the time from what we know, maybe two, and that’s it. In renesting, although, I did say they renested, from what we know, especially in the northern regions of their range that’s probably not all that common either.

Hank: Interesting. So an analogy for this would be if you’re an angler they’re like sharks. So sharks one of the reasons why certain species of sharks can be threatened, or even endangered is because they’re kind of the same deal. They do not birth as many young for the most part, and they take a lot longer to become an adult so that you can damage a population of either sharks, or band-tailed pigeons much more quickly than you can say mourning doves. And there’s this great book that I’m going to put a link to in the show notes it’s called Band-Tailed Pigeons. It’s by a guy named Worth Mathewson out of Oregon, and he describes the hunting of these pigeons in the 1970s, the early 1970s. This is back when the bag limit was around 10, or even 15 maybe.

And hunters, this is one of the very few examples, very few examples in American history where hunter effort was additive to the point where they were affecting the overall population of the animal, whereas, virtually every other game animal in North America is by design, and we talked about this at the beginning of the podcast. The harvest of them is regulated to the point where mortality from us shooting them is compensatory it’s not additive. So in other words, if there’s 1,000 pigeons in the world 30 of them are going to die no matter what, and it doesn’t really matter if they’re shot by hunters, or if they fall out of trees, or disease, or whatever, whatever, but if hunters kill more than that 30 in a given year that’s additive, and that’s what we don’t want, but this apparently happened to the pigeons in the ’70s. And I’m not entirely sure what the story is of how did that happen? Was it just ignorance?

Mark Seamans: The band-tailed pigeon management history, if you will, harvest management history I think you have to go back further around the turn of the century about 1900, 1910. You had two things happening. One was with the band-tail, and really we were at the tail end of the passenger pigeon, right?

Hank: Right.

Mark Seamans: So as folks may know the passenger pigeon numbered in the billions and now they’re extinct. As it turns out the band-tail, and the passenger pigeon are very, very closely related. They may be the most closely related species that there were at the time. So right about 1910, 1915, somewhere in there, there’s a gentleman at Berkeley, Joseph Bird Grinnell, he’s a famous ornithologist.

Hank: Oh, yeah, there’s a college name after him in Iowa.

Mark Seamans: Yeah, there’s a lot of stuff named after him, actually. He was quite the ornithologist, general scientist, and did incredible work, but wrote a paper, and there’s probably other folks. I don’t want to just credit him, but that’s what I’ve come across. It’s a prominent paper that’s actually accessible where he writes about the demise of the band-tailed pigeon. And I’m sure having just witnessed the passenger pigeon essentially go extinct by that point he was concerned about the band-tail because what was happening is you would have these massive hunts that were mostly occurring in Southern California, but they were also occurring in the North, too, around mineral sites which we can talk about, also, but these pigeons would congregate in different areas in the South during the wintering season.

Nobody really knows how many were shot, but you’ve got a population that might be 10 million, or something. Nobody knows either at the time, but that’s a ballpark I guess. And you might have been shooting over a million of them a year in a bird that can’t reproduce very fast, and not only that to add another layer to it part of the demise of the passenger pigeon was related to market hunting where professional hunters go out shoot as many as they can, pack them into barrels, put them on a train for market. Market hunting was actually occurring for band-tailed pigeons, also, at that time.

Hank: Yeah, so 1918 is the Migratory Bird Treaty so that’s a big marker for the beginning of the end of market hunting, but it’s my understanding that real end of market hunting it was sort of state by state in dribs and drabs all the way into the ’30s.

Mark Seamans: It was, but it seemed like for the band-tails there was some mutual agreement within the Pacific area that they were going to close the season, and the season as far as we know that was enforced the season was closed about 1913, 1914, I believe, until 1932 just because of this really great concern by these real prominent scientists at the time.

Hank: When did the last passenger pigeon die?

Mark Seamans: 1914, but they were extinct in the wild in the 1890s I believe.

Hank: Gotcha, so that’s probably the political, or emotional, or scientific basis for that like, wow, we just whacked the most populous bird in North America, and we don’t want to do this to its cousin.

Mark Seamans: Correct, yeah, maybe the most populous bird in the world people have speculated about that. It went extinct for a variety of reasons. Over harvest was definitely it, but it was coupled with some biology that the pigeon had, too. It didn’t avoid the gun was one of them kind of like band-tails. They don’t necessarily fly away once you start shooting their neighbors.

Hank: Spruce grouse are a little like that.

Mark Seamans: Yeah, grouse, Spruce grouse, yeah, dusky grouse, too, but with band-tails there was just this wholesale slaughter going on, and nobody really knew the magnitude except that it was great, and there was great concern. They closed the season, and then it reopened some years later. So there was some initial impetus by the states and folks involved before the Migratory Bird Treaty Act to get a handle on band-tailed pigeons. So when they opened the season again that’s when you had, I don’t remember, a 30 to 60 day season, but 10 birds a day was the bag, and that stayed in place up until really the mid ’70s.

And something else occurred at that time. There was some national monitoring programs for birds that were implemented in the ’60s called the Breeding Bird Survey. And it was able to track a lot of bird species. One of the species it could track was the Pacific band-tailed pigeon and there was just this decline, just relentless decline year-to-year in the birds that were being counted. And so beginning in the ’70s there was a restriction on the bag again. And so, finally, it just kept ratcheting down until we’re at our current level of two per day.

Hank: Yeah, two per day. So for those of you who are not familiar with this bird, or with hunting this bird there’s a good reason because hunting a band-tailed pigeon in this day and age is, and we’ll get into this a little bit more later, but is ceremonial to a large extent. I mean, even today, and I’ve only lived in the West for 16 years now, and even today you will see enough where you would think you’d be able to have a bag limit of bigger than two, but we just discussed one of the reasons why it’s low, and everyone is super to put it gun-shy, literally, of messing this up again.

So they’ve kept the season open. It only lasts seven to 10 days pretty much, and as a two bird per day, and six bird possession limit. So the harvest of this bird it’s got to be very, very low, and has been for quite some time, but there’s something about pigeon hunting, and we’re going to get into the actual hunting of them in a little bit that those of us who do it, and I try to do it every year really there’s something about chasing this bird that’s special, but talk to me a bit about where are we now in the conservation status of the band-tailed pigeon?

Mark Seamans: That’s a great question. To finish the thought of how we got to where we are really the ’50s and into the ’70s in the Pacific population you were harvesting two, three, four, 500,000 pigeons a year. Is that something the population could sustain? Maybe not. All evidence points to the populations reduced from the ’50s to the ’90s, 2000s. Folks have speculated it’s half of what it was today what it was in 1970. The harvest today when you look at the Pacific population is nowhere near what it was. It’s now in the tens of thousands, and 20 to 30,000 maybe. Many fewer hunters, of course, but the bag limit also has something to do with that.

So I’m not saying reducing the bag is what’s caused the pigeon to stop declining, and it apparently has, but it definitely could play a role when you think about harvest going from 500,0000 to 50,000 to 20,000, and so forth, but for the past 10 years, or so, it looks like at least for the Pacific Coast population it’s been pretty stable. And we’ve staunched this decline. For the interior population a whole different ballgame. Its numbers are in order of magnitude less than the Pacific population. We really don’t know what’s in Mexico, but north of Mexico in the breeding time of year we think there were 250,000 of these maybe in the ’70s. It apparently has declined, also, we think, and we’re unsure what it is in the interior right now. They’re still out you can still find them, but we’ve also reduced the bag and the hunting days like we did in the Pacific mostly because of the uncertainty. There was never that much harvest of the interior population. It was less than 10,000 a year always. And today it’s less than 1,000.

Hank: Wow, less than 1,000 birds a year in the interior.

Mark Seamans: It’s right about there, yeah.

Hank: I bet it’s 100 guys, too.

Mark Seamans: Well, we have such trouble counting the interior birds. They’re sparse, they’re hard to find. You can count them at bird feeders, but we don’t know what that means really, but we were also having trouble counting the harvest because there’s so few hunters. And we have a national Harvest Information Program, which some of your listeners, HIP, may be familiar with. You get a HIP stamp, and so forth. It just wasn’t working for the interior band-tailed pigeon because there were so few hunters we just weren’t capturing them in our sample, if you will. So a couple of years ago, two, three, in the interior population only we initiated a plan that if you were going to hunt band-tailed pigeons you had to have a special permit. New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah have a special permit. Arizona hasn’t joined yet, but I think they’re going to. So now we have a much better idea of how many people are actually hunting band-tailed pigeons in the interior, and what the harvest is we know who to survey.

Hank: That’s good. Okay, so I hunt birds in those states quite a bit. It’s usually free. You need your band-tail permit. Sometimes it’s five bucks, or whatever, but I hadn’t realized it’s to figure out who the hell is hunting these birds, we don’t know.

Mark Seamans: Yeah, because it’s free except in one state it is $5, but I think you get more people signing up than actually hunt, so you go back and survey them, and figure out, out of these 500 people who got a permit, 250 of them hunted, something like that, usually. And you know the success rate is not high on band-tailed pigeons anyway in the interior because they are hard to find.

Hank: The habitat requirements?

Mark Seamans: In?

Hank: Both.

Mark Seamans: In general.

Hank: Either. So this is getting into the hunting aspect of it, so if I’m going to look for band-tailed pigeons and let’s start where you are in the Colorado area if I wanted to look for them where do you even start?

Mark Seamans: I tell you what. I would start at bird feeders. Seriously, to find, not to hunt, but just to find them. I’ve actually tried to capture, and have captured band-tailed pigeons to band in the interior in Colorado. You capture them at feeding sites that’s the only way to do it here. They’re just so spread out on the landscape. They’re generally in the coniferous forest in the mountains. They’re going to move around a little bit probably year-to-year, and it’s related to food availability, so I don’t think there’s a limiting factor as far as the forest. It probably has to be some minimal height for them to feel comfortable, but other than that what do they need? They need that food source. They need those berries. And that’s pretty much how you look for them in the interior population.

As you get into New Mexico, and Southern Colorado, and Southern Utah, but New Mexico, and Arizona they do show up more in the oaks, too, which they like mast, and the pinyon as we mentioned before. Again, the nesting I don’t think is too specific. There’s probably at least some, what we call microsite requirements. They need a certain height and concealment, and so forth, but they just like to be where the food is, somewhere around the food. They can travel great distances. Pigeons are great flyers, so it’s not a big deal to fly 10 or 20 miles if you’re a pigeon. They have big home ranges where they can venture out.

Hank: I was wondering about that. I mean, one of the things with say quail is they can have a home range of less than a mile. I imagine that pigeons are just they’re a little bit more like ducks are like, yeah, I think I want to go 40 miles over that way.

Mark Seamans: Yeah, I don’t think they have much trouble. And I don’t know that we know how far they move in the interior too much within a feeding range because we just haven’t studied them that much, but in the Pacific it’s a little different. We use some radio telemetry techniques, and some banding and recovery, but in the Pacific the habitat requirements are similar. They’re in the mixed conifer forest. Usually in the northern part of the range it’s more of the lowland mountains, but all the way down to the coastline as you move south they get into the more pine oak, and oak forests in California. Again, related to food. They’re after the food. They’re after the berries. They’re after the mast. This is a good segue point into mineral sites.

Hank: Yeah. This is one of those things where this is another reason why the bag limit needs to stay at two until we’ve got a lot of pigeons so that we could maybe get three or four at some point, but this is the thing. Where I hunt them you and I both have said that we’ll hunt them as a target opportunity when something else is open so grouse, or quail, or whatever like, oh, there’s a pigeon and it’s the season let’s just get it. However, if you want to actually go to a place and get your two pigeons you’ll look for a mineral spring, and they’re dotted all over the West Coast both in the Cascades, the coastal range, and the Sierra Nevada.

And if you find them and you’re going to want to scout that out, and check and see if the pigeons are there in early September because when the season rolls around, and usually that’s in mid September you’re going to be want to be there because chances are you’re going to be able to see enough pigeons where you will get your two, and that’s all well and good in this modern era like I said it’s a ceremonial hunt you’re just getting a couple of birds every season, and not that many per day, now swing back to the ’70s and before like we were talking about where your bag limits were very, very high, and you can see that it’s a little bit borderline unethical to ambush them at this spot that they have to go to.

Mark Seamans: Yeah, no comment on that, but the mineral sites it’s interesting through time you can see our understanding of the pigeon use of those sites. You can see our understanding evolve because you can read some of the literature back in the ’40s and ’50s and folks were like, oh, they’re around these mineral sites, but we don’t think they’re using them. There’s some mention of that, but they are using them. We can go through that, but back in the day you get large concentrations of pigeons around these mineral sites. Hundreds if not thousands in the day, and there’s records in magazine articles from Oregon back in the day of private landowners allowing people to go on their property and just harvest a lot of these pigeons. They’re just sitting there. They don’t fly away. You can shoot them. They might flutter around. They might try and avoid you a little bit. They don’t really depart much. They hang around the same area, and as it turns out they were using those mineral sites.

Hank: What would they be using them for?

Mark Seamans: Well, minerals, of course, but it took some recent study. A colleague of mine in the Fish and Wildlife Service has a done a lot of work on this. His name is Todd Sanders, done a lot of work on the Pacific Coast band-tailed pigeon. And he has created a mineral site, and mineral sites. They’re artificial, but he can manipulate mineral concentrations and what minerals are actually in them, and through experimentation he found out that the real limiting mineral is sodium. People thought it was calcium, or potassium, but as it turns out the berries actually do contain calcium and potassium, things like that, but they don’t contain sodium, or at least not a lot. And so right now the understanding is that they’re going to these mineral sites to get sodium.

Hank: Like a salt lick.

Mark Seamans: Yep, that’s exactly what it is, and they don’t have to go every day. It’s every week or so as far as we know about the return rates as best we can monitor those. So you might see thousands of pigeons at a site one day, and the next, and the next they’re probably didn’t pigeons.

Hank: Okay. That’s really interesting. I mean, every organism, everybody needs salt in some way, but what is it about pigeons, and why aren’t there 50 other, or 100 other species of bird going to these same mineral sites for the same reason? What is it about pigeons that gets them at this effectively a salt lake that you don’t see raptors there, you don’t see hummingbirds there, or whatever?

Mark Seamans: It’s got to be diet. It’s got to be a lack of sodium in the things that they are eating because a good point of comparison is the interior band-tailed pigeons they don’t use these sources. They don’t use mineral sites, or salt lakes, or anything like that so the general thought is that in the interior sodium is just not limiting in their environment, in their food that they’re taking in so they’re not seeking out these places. Whereas, in the Pacific up and down the coast that must be the case.

Hank: Huh. Well, has anybody done a food study? It seems like we need to find a graduate student to do that.

Mark Seamans: It seems more opportunistic than what I’ve been able to see. There may be some out that I don’t know. They do eat a lot of berries. A lot of stuff that’s really rich in water, and stuff that really flushes your system, if you will, rich, juicy berries.

Hank: One of the things about the California coffeeberry, the cascara berries that you were mentioning is that you and I can eat those California coffeeberries, and they’re sweet, and they taste good, but if you eat more than a handful it’s going to give you the shits something fierce.

Mark Seamans: Yeah, and they’ve evolved to eat these things, but they’ve also evolved to use those mineral sites maybe as a compensatory measure to get salt.

Hank: Huh. Yeah, the budgies do the same thing in Australia those little teeny green parakeets.

Mark Seamans: Yeah.

Hank: I will walk you through how I tend to hunt them, and then I want to hear how you tend to hunt them. It’s very different because we hunt the different populations. So, typically, I’m going to go to the Sierra Nevada, and I’m either going to go to the east side, and hang around pinyon pines, so I need to be able to identify the Pinus monophylla, which is our pinyon pine. It’s a scrubby, stocky pinyon with very small cones that have big nuts in them. I’ll put a link in the show notes so you can identify that tree. And they only live on the east side of the Sierra. You won’t find them at the summit, or on the west side, but the first time I ever saw them was in a place called Ice House which is right off Highway 50. And the problem is I always see them when there are berries and other things around, but that area you can’t hunt it until December, and they’re not there in December, so that’s why I’m giving you a spot on the air.

Go ahead you can find them, but good luck seeing them in hunting season, but they like these big conifers, and they like drop-offs. They like really steep slopes because they will hang out in flocks. You almost never see just one band-tailed pigeon. You might just see the one, and then if you look you’ll notice that they’ve got all kinds of friends around them. And I’ve never seen a flock smaller than a half a dozen. I have seen them in the hundreds. So your general thought is if you are hunting, and you say, hey, there’s a pigeon, and you’re nowhere near humans like you’re nowhere near a town, you’re nowhere near a farm chances are it’s going to be a band-tailed pigeon because except in the winter on the Coast of California like in the Monterey area where they do hang out at bird feeders all the time, in the Sierra you don’t see them near people. So your first indicator if you see a pigeon in the forest it’s probably a band-tail.

Second, they absolutely love to hang out in flocks above gun range. You’ll see 18 of them at the tops of these huge ponderosa pines, or Lodgepole pines, and they’re standing there looking at you, and you’re standing there looking at them, and there’s nothing you can do because they’re literally out of shotgun range at the tops of trees. Ask me how I know. And they will just hang out. You just wait for them to move. What I have often done is once you spot a flock, and if they are out of gun range, which is seven times out of 10, you just wait, and you see where they go. If you have multiple people you can put them at different points within a few hundred yards of either side of that where they all are. And when they fly they typically dip into gun range.

And if you happen to be where they fly off to you can get shot at them there. This is sort of the typical way that we hunt them and tail them unless we find a mineral spring that they happen to be working on in which case then you can camp out by the mineral spring. Again, you’re only shooting two birds per person so it’s not like you’re going to really damage a flock that way. And then if you get to that point then you’re in a much better situation to get your two, but if not, you’re really just breaking your neck looking at them. And you can hear them. I mean, they sound just like regular pigeons when they fly that whistley sound. They don’t make a lot of noise otherwise, though. I don’t really see them as being very talky other than the typical pigeon coo-coo thing, but that’s really hard to hear when they’re 120 feet up in the air. Does this sound similar to you, or you do something else?

Mark Seamans: No, not at all.

Hank: Not at all, okay.

Mark Seamans: I suppose in some sense it’s similar. I’m not a big pigeon hunter for a good reason, I live in the Rocky Mountains. I used to live and work in the Sierra close to where you were, Hank, and not at Ice House, but there’s a well-known spring up by Ice House. I’m not going to say what it is, and there’s some other ones, too, but I didn’t hunt when I was in California at the time there, but I would just like to sit there and watch the things. And pigeons, these band-tails around the springs especially, or at feeding sites, too, they seem to lackadaisical. They can fly in, and it’s like, okay, we’re going to get to see them. They’re going to come down.

No, they’ll sit in that tree for two to three hours, and you wonder what they’re thinking, or doing. I’ve done this at capture sites where we’re trying to band them and it’s frustrating, but, also, at the spring up there by Ice House, too, but here in the Rocky Mountains I don’t really go out purposefully just for pigeons. They overlap in a season with dusky grouse here, so I’m more opportunistic, and what I’m looking for is a berry patch, or something, a well, a big berry patch. And out in the wild here that’s going to be your main possibility of finding them, but it’s not quite a needle in a haystack kind of approach, but it’s got to be close because I just don’t see that many, especially, during hunting season here in Colorado.

Hank: Of course.

Mark Seamans: It’s like some other hunting I do here. Some of these animals that I hunt, ptarmigan is another one here, I just don’t see them that often. I like to try just because I like to be out in the mountains here, but I just don’t see a whole lot of pigeons here. And there’s a reason the harvest of pigeons in the interior population is so low it’s because they’re fewer, they’re less dense, and they’re really hard to find.

Hank: So, okay, how many times do you go out looking for grouse, and in that time how many times do you see pigeons?

Mark Seamans: I go grouse hunting I try and get out about a dozen times a year. It may not always be that maybe a little more sometimes. I got a lot of sites staked out that I can drive to within an hour, hour and a half, so I like to do that. And I will see pigeons not often, but sometimes in the morning they must be leaving a roost to go somewhere else to feed because I usually see them flying high treetops. I’m not lucky enough yet to be at the right place where they’re coming down to feed.

Hank: But you’ll typically see them on any given hunt?

Mark Seamans: No, it’s pretty rare, actually.

Hank: Okay, I was wondering. So you go 12 times how many times do you see them?

Mark Seamans: Oh, just a couple times.

Hank: Okay.

Mark Seamans: Just a couple times. I live in the foothills above Denver, and they’re here, too. Every once in a while I see them, and it’s not even every year, but they’re here. You look at the bird blogs, or whatever they are. People see them, and they note them, and so people go and look at them, but they’re just not widespread here.

Hank: I fell in love with this bird because, A, I love pigeon hunting because I like to eat pigeons. There’s an allure to this at least in my mind. I hunt pigeons because I want to hunt pigeons the right way. I want to hunt them as a respectful hunter in the sense of I would like to hunt pigeons because I like to eat them, and I like the way they live. And I also want to hunt pigeons in a way that there will be band-tailed pigeons for millennia after I’m gone, whereas, our ancestors didn’t do that.

And so I feel like I’m trying to redeem the modern hunter in terms of this particular species because we did it so much wrong in the past that I want to show that you can still hunt this bird, and see its population not only be stable, but maybe increase. I mean, I know anecdotally, and, of course, the plural of anecdote is not data, anecdotally there are way more band-tails in my particular stomping grounds now then there were 16 years ago. I don’t know if that’s just a fluctuation, but I’d like to think it’s because we are giving them a break in the sense that, and I think it’s a nine day season, and a short season with a low bag and low hunter effort equals giving the bird a chance to come back.

Now some people would say, well, why don’t you just shut the season altogether like you did in the early part of the 20th century? The problem with that is to my knowledge there are only a handful of cases where the authorities whether it’s state or federal has shut down a season on a species and then reopened it since World War II. The snipe is the only one that comes to mind. Now there are some years where we can’t take any canvasbacks, for example, but that’s a one year deal. They’ve not shut down duck hunting. So I’m just going to say it like I don’t know that I trust the State of California, or maybe even the feds to reopen it if they were to shut a season down completely. And I think this remnant hunting that we’re allowed is while me, as a chef, and a hunter, I would love to have a bag limit of four, I’m perfectly okay with it being two until it’s ready to be four.

Mark Seamans: I was thinking because some of the stuff I was waiting, and you didn’t quite get to what I was thinking about, but I work on a lot of different species. And one of the commonalities that I run into you’re always trying to define why are you doing this? Why do you want to set the bag at two versus four? You’re always wanting to conserve the species right, but it also begs the question why don’t you just shut it down if there’s any sort of risk, or reduce it substantially? In working with the state books what I get a lot, what I hear a lot is being able to hunt is very important to some people.

It’s generally trying to maintain that tradition, and one of the concerns when you get to closed seasons, I mean, a closed season here or there maybe, but long-term closure you lose that continuity. You lose that culture. You lose that tradition possibly, and that’s a big concern for the state folks, especially. They’re way more in contact with the everyday hunter than I am. I interact with a lot of hunters, but these guys are getting who knows how many calls every day. These are on the ground game managers that I’m working work, and there’s great concern we want to maintain our hunting tradition. And so to perpetuate that closed seasons are difficult.

Hank: Yeah, I mean, it’s not good, I mean, on anything because I can think of the most significant season closure in my hunting and fishing career full-on closure there was a two year spot where we could not catch salmon in California, and that hurt. That hurt a lot. We couldn’t catch any anywhere. We knew it, we understood it, and they brought it back, and now salmon fishing is good again, but, of course, salmon is a species that comes back very quickly. Another one in my lifetime it was a sort of closure. So this is an interesting one. I grew up in New Jersey. Through my entire childhood all the way through college, so all my formative years, striped bass had a minimum size limit of 36 inches. Now I don’t know if you’ve ever caught a lot of striped bass in the East Coast a 36 inch striped bass is a monster. Why would you bother fish for them? There’s no point in fishing for them when the size limit is that big, so nobody fished for them. I mean, a couple of guys did because they remembered before, and they wanted to still be able to.

And this is what you’re talking about is that, yay, you could fish for them, but you could never keep one unless it was 36 inches or above. So for my entire formative years stripers were a pain in the ass because you’d always catch short ones, and you’d have to throw them back, and sometimes they’d be so thick that you can’t keep them. So it totally colors your view of a species and I could totally see with pigeons already it’s like you say you’re going to go pigeon hunting and nine times out of 10, no, 98 times out of 100 people think you’re just going to go to a dairy barn and shoot regular pigeons, but, no, there’s this band-tail. And most people don’t even know they exist even.

Mark Seamans: I don’t know if it’s a good analogy, but I like college football.

Hank: So do I, go Badgers.

Mark Seamans: No, go Gophers, but as we can see what’s unfolding in our country right now a lot of people they like it way more than I do. I’m an interested fan, but there’s a threat that we weren’t going to have a college football season, and there’s still some question about what it’s going to look like. I don’t know if that’s a good analogy for hunting, but hunting stirs those same kind of emotions that you’re seeing in the hardcore college football fan right now to me. I don’t know why that occurred to me. It’s probably because my Big Ten football is not on, but I think there is a devoted following of pigeon hunters who do this, and they introduce their kids to it, or their friends, and that perpetuates the tradition. So without that opportunity how is that going to work? I just don’t know.

Hank: So if you are hunting them this is the time where you might want to bring your 12 gauge out. I have shot them with a 20 gauge quite a lot, and that works. They’re tough birds. They’re tougher than the regular barn pigeon. I like to shoot them with bismuth sixes. If you are in a state that allows you to shoot lead, lead sixes fine. We can’t shoot lead in California, but you want a lot of pellets. You want them to be powerful, and you need to lead this bird like nobody’s business. It is them and along with their regular cousins they’re the fastest game bird in North America. Nothing flies faster than a pissed-off pigeon. They can hit almost 100 miles an hour.

Well, typically you’re not shooting at a fleeing pigeon so they’re half that fast they’re still fast. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen somebody shoot at either a band-tail, or a regular pigeon, and you see a tail feather come off like, yeah, they’re faster than you think. The other deal is because band-tails are typically in a forest I don’t find it ethical to shoot both of your pigeons in one volley because God forbid you lose track of one of them. I’ve never heard of anybody hunting pigeons with dogs. Typically, it’s just you and your gun. So if you shoot one and it falls it’s often going to be on some crazy slope in the middle of the forest, and you better just work your way down.

Now the cool thing about when you drop a pigeon is all of the Columbidae, so both doves and pigeons, their feathers aren’t really on very well. Like I don’t know, it’s a design flaw, or something, but as they fall through the branches they’re dropping feathers. And so when they hit the ground they’re dropping feathers. The gray feathers of a pigeon in the normally brown/tan forest floor that’s going to help you find that bird if you don’t see exactly where it lands. And since you only get two don’t lose any birds. That’s your main job. Don’t shoot them where you can’t recover them, and do your damnedest to recover them. I did want to ask you I had never heard of anybody using dogs with them. Have you?

Mark Seamans: No, I don’t. Every once in a while I use a dog for grouse. My dog loves the forest. I don’t know how good she is on grouse all the time, but I don’t know of anybody. It’s usually, especially, in the Pacific people are waiting by a food source, or a mineral site. So a dog is really not necessary. Think it through.

Hank: That was my thought, too. Are you with me on the pretty powerful number sixes or fives?

Mark Seamans: I’m walking around with sixes, so that’s what I use, but, again, I’m not a big pigeon hunter. I don’t have the opportunity, so I can’t say one way or the other, or that’s the right load in my opinion.

Hank: I want to finish this up with the eating aspect of it. Now I’ll go back to what I just said about the feathers not being on very tough. For the love of all that is holy in this Earth, or any other, please pluck your pigeons, I mean, you only get two. Chances are you’re only going to kill six in a whole season. It’s not that big a deal. It takes about two minutes to pluck a pigeon, and it’s super easy. It’s the easiest bird. Doves and pigeons are the easiest birds to pluck there is, period, end of story, so pluck them. They are the size of about a chukar, so they’re partridge size. They’re a little bit bigger than a regular pigeon, and they’re maybe three times the size of a mourning dove. They are all red meat as all their friends are. And they can live a long time. A little side note. Do you know how long they normally live in the wild?

Mark Seamans: Pigeons on average once they make it out of the nest probably five or six years, but I believe there’s records up to 20.

Hank: Yeah. Well, doves are plastic like that, too. This is the other thing about doves will always be tender because chances are we talked about it in the dove episode. I know personally of at least a four-year-old male mourning dove because Holly used to ban them for the State of California, and this has been years since she’s done it, and there’s still one kicking around, but typically they only live less than a year. So if you’re talking about a pigeon that if it makes it out of the nest it’s typically three to six it’s going to be a bit tougher from a cook’s perspective. It’s a bit more like waterfowl than it would be like a quail, or a chukar, which all the chicken birds live fast and die hard. Pigeons, I mean, their main enemy are raptors. They’re primarily caring about hawks, so. They fly fast. They fly afar. They’re tough, and they’re long-lived, so that tells you a few things.

I still deeply love them pan roasted, and typically because it is that one ceremonial meal that I’m going to do in any given year. I will pluck the bird, cut the backbone out, and I will take the legs and separate them from the crown. Now I’ll show you pictures of it in the show notes. So basically what you get is you get the two legs, and then you get the crown, so the breast with the skin on the bone with the drummettes the first digit of the wing. Each pigeon is in three pieces, and if you pan roast it in a frying pan with some high smoke point oil you can then control the heat on all the parts of that bird so that you don’t overcook the breast of a pigeon.

So a pigeon like any red meat bird you’re going to want to serve it medium to medium rare. You do not want to long stew a pigeon if you can help it. Now there are exceptions, and my mind is immediately going to something like a bierock, or a runza, which is basically a dough with meat inside, or a pot pie, or a pastie, or something like that. Those would be options, and those are actually very traditional ways to eat pigeons. Now that said, it’s a band-tail, so while I might make bierocks, or a pot pie with barn pigeons, band-tails are special. They’re super special. The other cool thing, and we’ve talked about it the whole episode is what do they eat? They eat acorns. They eat pinyon pines. They eat berries. Virtually everything that they eat and I’ll put a link to a food habit study of band-tailed pigeons that I’ve read several. Virtually everything they eat is delicious to us as well.

So my advice is always, well, look where you are when you shot that pigeon. Pick those berries. Process some of those acorns, or do something. Make this one meal that you’re going to get a special thing, and make it taste of the environment that you’re in. Well beyond any other culinary advice I can give you on band-tails just make it an event, make it a date night, make it something special because this bird is among thee most special birds in North America. I don’t know if you have anything to add to that, but that was my soapbox.

Mark Seamans: No. I don’t think your audience would like me to tell them how I cook game birds. It’s really usually pretty simple. I will roast them, usually, but I obviously don’t go into the great thought you did. I will add I think one of my favorite ways to cook, and I haven’t had the opportunity to shoot a band-tailed pigeon when I’ve been out camping, but is over a tripod, and just a smoke and water steam mix. I’ve cooked grouse that way which don’t really need much. My experience with a lot of these game birds that are eating the berries and stuff you don’t have to put a whole lot of seasoning, or anything with them. You can cook them with the berries, eat them with the berries, whatever, but just over an open fire with that steam and smoke is probably one of my favorite ways to prepare them.

Hank: It is, it really is. I mean, there’s something about smoke in pretty much any game application.

Mark Seamans: Yeah, but, also, a little foil over the top sometimes with just some water, or some beer even. It depends how adventurous you’re feeling I suppose, or wine, if you have that just to get a little bit of that steam going in there, too.

Hank: Yeah, especially, pigeons because they’re long-lived they can be tough so you got to be more careful when you cook a pigeon than you would with a dusky.

Mark Seamans: That’s good to know.

Hank: Yeah, chances are a dusky is going to be a year or two maybe if you get a big boomer. Think about a steak you buy at the store. Really the typical steak is going to be a year and half old, whereas, now think about a trophy mule deer. You eat mule deer. How old is your trophy mule deer? Seven or eight, sometimes older, and it’s literally a whole different animal in the kitchen. So is there anything that we should have talked about band-tails that we missed?

Mark Seamans: I really can’t think of much off the top of my head.

Hank: It’s a cool bird. I mean, I encourage everybody out there who has a season to pursue it, and even if you don’t get one it puts you in really good territory. And like you said just go grouse hunting and look to the skies, or you’ll hear them. They sound like pigeons. So you’re like, holy shit, it’s a band-tail let’s get it.

Mark Seamans: But like you said my experience with them is they’re flying at treetops. They’re moving like a bullet for whatever reason.

Hank: Oh, my God, yes.

Mark Seamans: That’s always like, well, those were band-tails I’m pretty sure.

Hank: I think they cruise at 50 miles an hour.

Mark Seamans: They can, they can go really fast. I don’t remember what the recorded speed is. Especially when you see them you know they’re moving between feeding mineral site something, and they’re just great birds for distance they’re incredible.

Hank: And they’re pretty.

Mark Seamans: Yes, they’re gorgeous, especially in the hand they’re really gorgeous. Having captured quite a few of them they are really gorgeous.

Hank: It’s interesting there’s no pigeon society is there? I mean, like Pheasants Forever, or Quail Forever, or Ducks Unlimited, or California Waterfowl. I don’t think there is anything for pigeons is there?

Mark Seamans: No, not that I’m aware of.

Hank: Anyway, I really appreciate you coming on. How can someone get in touch with you if they want to talk with you about pigeons?

Mark Seamans: My email would be the easiest. And you can look me up, Mark Seamans with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, mark_seamans@fws.gov

Hank: All right, I will put that in the show notes. Once again, thanks a lot for coming on. This has been a great conversation, and I’m going to try and turn this around quick enough so that people can actually listen to it while they’re going to a pigeon hunt.

Mark Seamans: Sounds good. Thanks Hank.

Howdy Hank,

Many thanks for featuring Band Tail Pigeons. They migrate through my home turf and some years remain through summer. I’ve yet to bag any. But three zoomed above several days ago when Arlo, my shorthair and I were along the neighbor’s ridge. It would not surprise if migration proceeds the season again as last year. For the few of us in quest of this quarry, it would be reasonable allowing personal discretion determining season vs defaulting to the birds to observe CAFW season.

Especially decent of you to transcribe the podcast. My impaired hearing is severely challenged by recordings. Reading works much better.

Btw: Pheasant Quail Cottontail is outstanding!

What a great episode!! I am fairly new to Band -tailed Pigeon hunting (within the last two years), but where I hunt, I would not have found the birds I’ve downed without my dog. At the very least it would have taken me a hell of a lot longer, and in some instances, maybe never have found them. In terms of locating them, I’ve concentrated on what they feed on around my area which is Cascara and Blue Elderberry and also what time of day they are coming in to feed. As noted in your discussion, it also coincides with where I hunt grouse, both Sooty and Ruffed. I shot two band-tails last year and ten this year. Scouting pays off…as well as a good dog!! Also, it may be one of my favorite tasting game birds ever.