As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

It has often been said that there is a fine line between a hobby and a mental illness, between focus and obsession. I’ve spent plenty of time on that line. I am there now.

Beer is the current object of my infatuation. Not so much drinking it, although that is the endgame, as making it. I’ve been drinking beer more or less continuously since I was fifteen (don’t judge me) and I’ve been making mead from honey and wine from both grapes and other fruits for more than two decades. So I am a stranger neither to the product nor the mysteries of making alcohol.

But, until recently, I’ve not been a brewer. Now I am.

This has all been building for quite some time. For decades I passed on brewing, telling myself I can buy better beers than I could ever make as cheaply as I could if I went to the trouble of setting up a homebrew system.

And then there was the scary issue of sanitation. Beer brewers are almost as hyper about sanitation as surgeons – a far cry from the lassiez faire cleanliness necessary for making good wine. Wines typically contain twice as much alcohol as beers, and as we all know, alcohol cures (and causes) a multitude of ills.

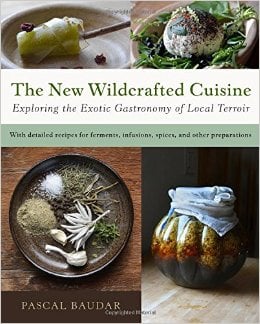

But the more I got into drinking beer, the more I learned how much vaster the beer landscape is than the world of wines white and red and pink. And the more I learned this, the more the germ of an idea began to grow within me. The spark that made it break the surface was my friend Pascal Baudar’s new book, The New Wildcrafted Cuisine.

Pascal is, like me, a crazy forager and maker of odd and wondrous foods from wild things. Pascal also happens to be Belgian, a country with a strong brewing tradition. His book’s sections on wild “beers” fascinated me, got me thinking about where I could take this idea.

First off, I decided I needed to tackle the mystery of grain. Pascal does not do this in his book. (He is now, by the way.) All his beers lack malt, thus my quotation marks around the word. To me, beer equals grain. This is what defines it from cider or mead or wine. And getting fermentable sugars from a grass seed is something of a miracle, if you think about it.

The process involves sprouting the grain, then drying it to halt the enzymatic activity that converts the starches in, say, a wheat seed into sugars. Your saliva will do the same thing, incidentally. Remember chewing Wonder Bread dough balls until they got sweet? I know I did, back in the 1970s. (It was a simpler time.) To release those sugars, you steep the malted grain in hot water for a while, and then you can ferment the liquid.

I will admit I am still daunted by this. I buy my malt from a homebrew store. But it is only a matter of time. Incidentally, my girlfriend Holly has been predicting my obsessions for years now, and it is important to note that having a tolerant Significant Other is a vital part of this process…

I am telling you all this not only to let you know that you will be seeing more recipes for beer and cider and other alcoholic drinks on this site soon, but also as a way of giving you a look inside my restless mind – and by so doing, maybe helping you to dive into whatever it is that has you teetering on the edge of happy madness.

I should tell you I keep notebooks. Lots of them. Have been, off and on, for 20 years. I scribble in them constantly. Recipes, flashes of insight. Dumb ideas. Essays about my life I do not intend for personal consumption. But above all, notes on process. These notebooks are vital to the process.

I might write a single sentence: Hot oak-on-oak action – acorn nut brown ale aged in French oak. (Yes, even though I am in my forties, I cling stubbornly to the 12-year-old inside my head.) How do I make a brown ale? What would it take to get acorns in there in a way that’s nice to drink? All that comes later. It’s the notion, the idea that matters now. Keeping records is important.

A long time ago, I earned myself a master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin (Go Badgers, Hey!), and while I rarely need my advanced degree in African history, that training is vital in one important way: Graduate school taught me how to survey literature to get a firm grasp on a subject.

We all know that guy (it’s usually a guy) who read one book on a subject and is now an expert? Yeah, no. These people are intolerable if you actually do know a topic inside and out. Don’t be that guy. What grad school teaches you is that if you want to understand how to make beer, read lots and lots and lots of books on the subject. Over extended reading, you get a sense of what is solid, what is debatable, and what is, well, idiosyncratic, to say the least.

I own more than 100 books on foraging, for example, and I am pushing 20 on beer brewing. Yes, I read quickly and constantly. Another trick you learn in college.

Books are one piece of all this. Another piece I learned from being a newspaper reporter, a profession I held for 18 years. Being a reporter means learning new things fast. Part of the profession is knowing how to properly search the internet – Google Scholar is a treasure trove of scientific information, if you are so inclined – and part of it is having the guts to admit to total ignorance about something, and asking those who do know to share their knowledge.

In this case, it was hours spent on homebrew websites and forums, and hours more drinking beer with homebrewers and the guys over at the local brew shop, picking their brains for tidbits.

Finally, there is the most important piece of all: Doing it.

As I’ve mentioned, I know how to make mead and wine. I started back in college and have never looked back. And so the first brew I made was right out of Pascal’s book: Mugwort and lemon, no malt. Sweetness from turbinado sugar. I followed his directions, let the drink ferment and, 10 days later, bottled it with some priming sugar so it would be carbonated.

This, I must tell you, was what a certain techie set would call a “pain point.” Or let’s just be frank: Carbonated bottling scared the shit out of me. Nearly everyone who brews knows someone who overcarbonated some beer or somesuch and had it explode, sometimes with horrific results. They don’t call them beer grenades for nothing. But I trusted Pascal, and it worked, more or less. (A bottle I opened some months later did gush pretty badly.)

Then came the early true beers. Baby steps. I began with a hybrid of real grain mashing and using malt extract, which is what I am still doing. All grain will come in due time. The long boils and intense cleanliness needed in beer was a new one. But I played along.

My first beer was wretched. My fault, of course. Me being me, I was not about to start with some lager or pale ale. No, I started with a gruit, a beer made without hops. I used a combination of local herbs similar to those found in this medieval brew, and, well, let’s just say that the adage that less is more is real truth. This beer was so damn bitter I dumped all but one bottle. And if that last bottle winds up tasting good in a few months, I will be sad. But at least I’ll have learned something.

I’ve since made that beer two more times, and this third batch I am quite happy with. I’ve also made several other beers using wild ingredients I am either ready to release on the world, or close to it.

Since I began this obsession five months ago, I have brewed almost every week – and twice a week a few times. The initially steep learning curve has leveled considerably. I can now talk and walk with at least the confidence that I have an inkling about what I am doing. Every day I learn more.

And yes, it may not sound like a long time, but in those five months I’ve basically read every major book on brewing, talked with scores of more experienced brewers, read scholarly articles and scientific papers, online articles, forum threads (and rants) – and, most importantly, I have brewed beer nearly 20 times. Admittedly, I still have a long way to go. But this is what zero-to-sixty feels like when I am learning a new skill. It is exhilarating.

And now, about that hot oak-on-oak action ale…