As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Years ago, I watched a hunter skinning and cutting out the breast meat from a drake canvasback. I stood there, mesmerized. It was the first canvasback I’d ever seen in the flesh. Canvasbacks, if you are not familiar with them, are the king of ducks — so prized that it would cost $125 in today’s money to order one in a restaurant, back when this was legal nearly a century ago. Then and now, canvasbacks are a treasure at the table.

You do not skin and “breast out” such a treasure. Standing there, I found myself physically repulsed by what this guy was doing. For a long while I couldn’t even open my mouth for fear of what might come out of it. Finally, I approached him and, swallowing my emotions, asked nicely if I could have what was left after he’d skinned and breasted out his can. “Sure,” he said, looking at me like I was insane. “I was just going to throw it out anyway.”

In the years since, I’ve managed myself as best I could. When I see people skinning and breasting even perfectly shot, beautiful birds, I just look away. I try to forget about it when I hear comments like “the only legs I like are on a woman.” After all, most of the hunters doing this are good people, friends even. And the last thing I want to do is stand there haranguing people about what they should and shouldn’t do with their birds.

I understand why many hunters breast out their birds. If I were raised in a hunting community and everyone around me breasted and skinned our birds, chances I’d do the same thing. inertia and tradition are powerful forces. How a person perceives food makes a huge difference, too. If you view food merely as fuel, eating the animals you shoot becomes more of an obligation than a joy. You do it because you are supposed to, not because you prefer pheasant to chicken, or venison to beef.

But even though I understand why hunters breast out their birds, it does not mean I have to like it. For me, breasting out a bird shows disrespect for the animals we say we love. Consider this: As hunters, one of our strongest arguments when we’re trying to convince non- or anti-hunters that we are not in fact callous killers is that we eat what we bring home. Breasting out birds and tossing the legs, wings and giblets in the trash damages – some would say destroys – that argument.

I’ve heard all the excuses. “Coyotes and buzzards gotta eat, too.” Sorry, but we do not hunt to feed scavengers. I have also heard endless rationalizations about how it’s OK to dump the legs of pheasants, ducks and geese because they’re inedible, which is horseshit.

Even I don’t make duck scrapple, and I am, admittedly, an outlier in the hunting world. I am fond of telling people that I use “everything but the quack” on a duck or goose, but I still toss the feathers, intestines, lungs and head – although recently I have begun saving the tongues to make Chinese dishes.

A stronger counter-argument, however, is the very real truth that what I might view as good eats is another person’s trash. As hunting ethicist Jim Tantillo of the Orion Institute says, “Where one hunter sees pickled moose tongue and stuffed elk heart, another hunter sees food for carrion beetles and ‘the marvelous process of renewal.’” It is wrong to suggest that you cannot an ethical hunter if you don’t happen to enjoy making your own duck stock, or eating liver pate. And, scavenger argument notwithstanding, Tantillo has a point about that “marvelous process of renewal” — but only if you leave the carcasses of your birds in the field. If you toss them into the garbage can, that renewal will only occur at the city dump.

To my mind, this slippery slope of what ought to be eaten from a duck or goose ends at the supermarket. Walk into any market in America and tell me what you see: chicken breasts, yes, but also drumsticks, legs and thighs. Ditto for turkeys and ducks, too.

Make no mistake: Hunting is a privilege that can be taken from us. If society sees hunters as wasteful rednecks who can’t even be bothered to toss skinned pheasant legs into a crockpot with a can of cream of mushroom soup, we are in deep, deep trouble.

I am not saying we all should be required to pluck every bird we bring home, nor am I saying that everyone must eat giblets and wingtips and such. Sure, I do. But like I said, I am an outlier, a freak even. Surely there is some societal norm that we can all agree to about what parts of a bird ought to be kept?

There is, and it’s in Montana, a state with more hunters per capita than anywhere else in America. Montana has a law that requires hunters to use the legs of every bird they shoot larger than a partridge – if you’re not a hunter, that’s about the size of a Cornish game hen. So in Montana, you must use the legs (skinned or plucked, either way) of pheasants, ducks, geese, turkeys and grouse. Most of us would agree that this is reasonable, no?

But let’s face it. No law will prevent those who don’t want to eat the legs of their game birds from tossing them in the trash. Legislating morality is a dangerous game that often leads to zealotry and unintended consequences. The bottom line is that what I think or support doesn’t matter. What matters is what you think.

One of the primary reasons I run Hunter Angler Gardener Cook is to get hunters to want to eat more parts of the animals they bring home, even if it is just in a crockpot with cream of mushroom soup. It’s why I’ve been doing what I’ve been doing for five years now. And let me tell you, one of the things that keeps me so excited about HAGC is the steady stream of email I get from hunters who’ve taken a chance on cooking legs, wings, gizzards, etc., and are writing to tell me how much they enjoyed it. Emails like that make my week.

If you are one of those hunters, here’s the best present you could possibly give me in 2013: Find some skeptics and cook for them – only be sure to cook the legs, wings or giblets of whatever game bird you have in your home. Pheasants, ducks, geese, it doesn’t matter. If you can convince just one more person to save the legs on his birds, we’ve all won.

And if you happen to be one of those skeptical hunters, I humbly ask you to try any one of the recipes for legs or wings that you can find on this site. Just try it. For me. If you do, I’m betting you might just change your mind.

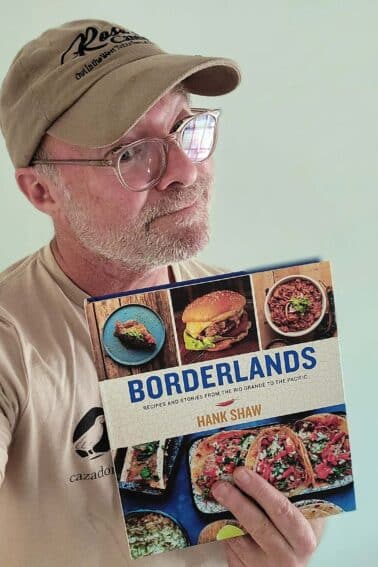

I make my own duck/goose stock and it makes all the difference in the final taste of my waterfowl dishes. I am looking forward to Mr. Shaw’s new waterfowl cookbook.

Josh, amen to that. Sorry if I misunderstood you.

The hearts and livers of game birds, even doves, are delicious lightly floured and sautéed in butter. I have convinced a number of people, hunters included, that these parts are worth saving.

I think legs and thighs are the tastiest part of pheasant. I just returned from a pheasant hunt – my buddy wanted only breasts – I got twice as much of our shared birds by taking all of his birds legs and thighs.

River Mud, I appreciate your comment to an extent you probably wouldn’t believe. However, I didn’t say that they weren’t “living in the country” as much as they should, but rather that they aren’t “living country as much as they should”, which can happen wherever one lives.

Hank

I was at an old school english driven game shoot a few weeks ago, the guns as the sports are called, all took home a token brace and the rest of the bag were to go to the game dealer. The head keeper was kind enough to give me a feed sack of birds, everyone from the keeping team i spoke to said the legs of both pheasant and partridge weren’t worth eating. I was amazed. I’ve always eaten all the flesh and now thanks to you and your writing i’ve got all the organ meat in my freezer too. I did feel I was letting you and myself down when I chucked the gizzards though.

SBW

Hank – I’m in agreement with full utilization of what we shoot. This idea is one of the 7 sisters of the North American Wildlife Conservation Model.

Nothing disgusted me more as a hunter and a game warden than the ‘shoot it and leave it’ criminal. In my mind the lazy ‘strip out the best cuts and leave the rest’ crowd wasn’t far behind.

However, I just finished reading a book, “Life Everlasting, the animal way of death”, by biologist Bernd Heinrich, that made me re-examine my human centered view of waste. I still will use every bit of the critters I shoot (I have a bunch of moose bones boiling on the wood stove right now) but depending how the non-human utilized parts are disposed of, I don’t feel so strident about it being waste. Human waste, yes, but certainly not for ravens, coyotes and scarab beetles.

My thinking now is not fully using what you kill is disrespectful to the animal killed. If this is true, then it follows that the disrespect probably extends to other wildlife and wild places. If the unused meat/other parts are returned to the land – then waste is not the issue.

I’d agree that there’s NEVER any shame in that asking. In fact, too many hunters are willing to give away entire birds sometimes, because they just don’t feel terribly motivated to dealing with the bird they’ve killed (though they will, to the minimal extent (breasting)). My wife always asks for my pheasant feathers, and I gave up an entire wood duck’s feathers for a fly tying friend.

People are more generous than each of us may think. As in most (legal) things in life, there’s no harm in asking.

I used to be guilty of this and decided to change for various reasons. I now keep the legs and other parts and cook the meat to use in croquettes, tacos, or quesadillas.

This is a paradigm I’ve tried to change in the three seasons I’ve been hunting. When I started, I met the old school hunters who just tossed the remainder away, and I was sure to ask them for any parts or birds they were not going keep for their own table. This methodology continued, and as I became a more successful hunter, I would find ways to share my dishes with them in an effort to show what they were tossing was actually delicious edible portions of the bird. My second season I went so far as to even keep the unique feathers from the ducks I harvested and had earrings made from them for the ladies in my family which I gave to them for Christmas.

I never found shame in asking these hunters for these portions, and this season I was rewarded with Swan thighs and legs that I will be cooking up soon. I just hate seeing these parts tossed away.

This season, as I began to hunt with new people, the question always came up regarding how they cleaned the birds they brought home. I was pleased to learn that many of my new friends were up to plucking their birds and utilizing a majority of their harvest. Maybe there is a paradigm shift occurring. We can all hope cant we? And until that time, we can all do our part to save and utilize these portions and do justice to those animals that gave their lives for us to enjoy them.

Erika, I think I’m understanding more where you’re coming from and it makes a great deal of sense. Thanks for the further detail.

Josh, whether everyone “should” live in the countryside or not, that ship sailed about 4,000 years ago when rich people started consolidating poor people (and slaves) into camps and villages to increase the efficiency at which they produced work. With 7.1 billion people on earth (soon to be 10 billion before the inevitable skid, crash, or slide), everyone can’t – and shouldn’t – live in the country. To accomodate all of my area’s wannabe countryside inhabitants (who still have to drive to work in the city 50, 60, even 90 miles away), our interstates are now 8 and 10 lanes wide. That has not accomplished a dang thing – except eliminated a lot of wildlife habitat and hunting land.

Holly, I think investing time and an emotional connection with one’s food is a great place to start for most of us, whether we hunt or not. My folks have been raising and butchering their own chickens for some time, and the cost and effort that goes into that is certainly not reflected in the chicken I admit I bought at the grocer’s today. But I hate wasting even cheap food, and can’t afford the dishes I read about in restaurant reviews, so I’ve started looking around for what I can do with what other people wouldn’t even bother buying, let alone cooking. My folks waste little, even the chicken feet are saved for gelatin stock. And the bag of frozen gizzards were confited after I’d read Hank’s directions for duck gizzard. None of us could believe what tender morsels those tough chunks of muscle were transformed into.

I bought domestic duck for Christmas, and hardly a scrap went to waste. I like my breast rare, with a crispy skin; when I looked for the leg confit recipe I’d bookmarked, it also turned out to be Hank’s (and the gizzards and hearts got thrown in). I roasted the wings and carcass for stock, and the picked meat went into pan-fried neck-skin sausage. Every drop of fat was saved, some of which went into a liver pate. And the what was left of the bones went back to the chickens ha ha ha! I doubt even the most blase hunter would turn their nose up at any of these dishes.

Anyways, I’m glad I get to practice on store-bought birds; if I ever get the chance to cook a wild duck, I hope I can do its life justice with as many dishes. Tossing a bird away after breasting it out would be, to me, like throwing out confit, crispy sausage, pate, several wonderful bowls of soup, and a platter full of crispy duck-fat potatoes. That would be crazy!

Hank,

Really emotional topic judging by all the responses. I think to use the animal to the best of it’s entirety is a very native, primal, and tribal instinct. When our ancestors hunted it was for survival and every little bit that could be consumed, was. Not only for necessity, but also as homage and respect for the animal that gave its life so that they could live. For me your site has taken this instinctual aspect and applied classic & modern fine cooking, that entices the readers and inspires hunters to eat out side the box or breasts for that matter. Thank you for inspiring us to try and eat all but the Quack!

PS: Waiting on that Duck Cook Book? Get “Quacking” on that sucker!

Hank, great post. I think what you are coming up against here is quite deep and complex:

First, you do feel there is an ethical argument to be made (“wonton waste”, to which I reply “I never waste wontons, I grew up in Chinatown”), yet you feel uncomfortable about it because you are a journalist from New Jersey (that’s a joke);

Second, because you ask people about wasting parts (which is specifically forbidden in many states because many hunters and game managers believe it is wrong behavior, too), people get uncomfortable (either mad that it happens or uneasy because they do it… and, why would they feel uneasy if they didn’t really know it wasn’t right?) – these reactions add to the evidence that there is, in fact, an ethical argument to be made;

Third, people do what their daddy’s taught ’em, but they also do what society teaches/pressures them to do (I’m reminded of a great article in “A Hunter’s Heart” about a daughter getting bullied at school in Alaska for eating Dall sheep), and in the US, urbanization has crept into all but the most distant of rural communities.

This last point is to highlight a reasoning you make to help you feel better about some people’s wasteful habits: You say they see food as fuel. But, that isn’t true, or else we wouldn’t have the obesity crisis we do. People enjoy eating, it’s just that urbanization (its efficiencies and its homogenized tastes) has taken away the regional flair and diversity of tastes and textures. Those same folks who don’t have the time to skin a pheasant leg and throw it in the crock pot with some potatoes and onions before sitting down to watch the game will usually sear a marinated steak to perfection (same amount of time) or put a seasoned chicken on a beer can (more time). At the very least, they know somebody who can do those things.

I have a two year-old and a six year-old, and we just pounded out some dadgum acorns for a freakin’ cake while watching the Georgia Bulldogs beat Nebraska the other day, AND while I had an in-depth conversation about gun control. It isn’t about time, it’s about inertia and social pressures – it’s about letting city-fied living creep into your existence. If I’ve offended some, it’s because they feel bad that they don’t live as country as they should.

As for defending hunting: If we can’t even talk about marginally illegal activities just so we don’t offend some folks who enjoy the sport as they like it, then we are in a bad, bad place. Hunting has to weather honest scrutiny from within, or it will die off.

Erika, it’s funny – it was only when I started hunting that I stopped cavalierly tossing meat that I hadn’t cooked before it had gone bad, or even tossing uneaten food from my plate (rare – I like cleaning my plate). Having watched the animal die, having caused it’s death made it very personal, and wasting it seemed so dishonorable.

It’s also a function of the work: I spent 15 hours hunting on Jan. 1 and 2, and seven hours driving to and from those hunts, and five hours plucking and dressing the seven birds I killed in those two days. That’s 27 hours for at most a couple pounds of meat. That’s a big investment of my time.

And for everyone who doesn’t know what to do with legs, here’s what I do when Hank abandons me and I actually have to cook for myself: If I don’t roast the duck whole (my favorite), I cut everything off the bone into stirfry-sized pieces and make an easy stirfry, cooking the meat very quickly to avoid making it livery.

Holly and River Mud,

I think the “problem” isn’t just with hunters, it’s with the attitude of that same majority of Americans towards their food in general. The amount of food that goes to waste here, literally into the trash, is appalling. Like tens of billions of dollars a year appalling. And yes, I’ve seen kids filling their boat with bluegill they’ll never eat, just to see how many they can catch. (I’m thankful not to have yet seen a deer’s carcass left for the sake of its rack, but to my naive mind that’s more like poaching or even psychopathy than hunting…)

Which is worse, not comprehending where your food comes from and scraping a quarter of it off your plate into landfill; or taking down an animal just for the experience and the few choice morsels of flesh?

I’m not pointing my finger at hunters, and I think we’d do better sticking together and being willing to hear a gentle admonishment on occasion rather than name-calling and defensiveness : )

Hank,

I’m from Chicago originally, but moved to Tennessee years ago and now work in EMS. Everyone I work with hunts. Unfortunately, everyone breasts out their birds too. Hunting is still foreign to me, but not the cooking part. With the primer from your book I started requesting whole birds two weeks ago when my buddies went hunting and promised to return plucked, waxed and gutted birds ready to go in the oven. They’ve all been shocked. Guys who didn’t know the difference between roasting, braising or boiling now don’t want their duck without the legs, skin and delicious fat. Plus they’re definitely bringing me more birds for my table too. Win, win. Thanks for all the info over the last year–it’s creating converts in Tennessee, and I promise, that’s saying something.

I have also shared the experience of watching someone breast out a canvasback, when I was first starting to duck hunt. I had to walk away before I said something I shouldn’t, I couldn’t watch it. Since that time I have tried to educate people about making use of more of the bird, with mixed results for sure. But I am excited when friends and acquaintances tell me that they tried recipes for parts other than breasts, even if they didn’t turn out well. They are at least trying to use more of the bird, and they will eventually find a recipe they like, and the next time they will be excited to make use of those duck legs (or whatever part). Hank’s recipes have certainly helped me educate a few people with recipes to use more of their birds.

As per previous comments about Hank being maybe a bit “preachy and holier than thou” on this subject; I can tell you that is exactly the opposite when you speak to him in person. Maybe the page title of “wanton waste and breasting out birds” stirred up a hornets nest with a few people, but its more a matter of perspective. In Montana as Hank stated, breasting out a duck and throwing the rest away for example would actually be wanton waste. In California that is not the case. Something that sounds “preachy” in California is the norm in Montana. All you can do (as Hank does very well) is educate people about their options, its up to them to decide to change their minds or not. Don’t get bent out of shape, take it with a grain of salt, try a new recipe to make use of more of the bird, eat, drink, and be merry!

Erika, I agree 100 percent that people like you are who we need on our side. We don’t need a majority of people to hunt; we need a majority of people to be comfortable with what the majority of hunters do. How we make use of the animals we kill is an important part of that.

Ugh. **too** often.

Erika,

The vast majority of Americans (80% or greater, I’d guess) don’t even understand how a chicken breast is attached to a chicken (Food Prep 101), or why birds have pronounced breast muscles at all (Biology 101); I highly doubt that a large amount of them are appalled by the waste of parts of a bird that they would not eat a single bite of – if they saw the meat attached to a head, skin, feathers, or feet prior to it being prepared in an oil fryer.

Displays of wastefulness and offensive redneckdom are helpful to no one, but I still fail to see how openly calling the most dominant American preparation method of wild bird “wanton waste” (which is an important and sensitive legal term to bird hunters) is the kum-by-yah, inclusive approach that you, and others, suggest that it is.

Don’t know about where you live, but out here we have wanton waste. Deer with sawed off heads, let to rot in the woods. Entire piles of dozens of unwanted, unfilleted geese and ducks (a very, very common occurrence). Rafts of floating dead croaker that EVERYBODY wanted to catch and put in the cooler but NOBODY wants to clean. That is wanton waste. Losing 15% of a bird’s meat by not using the neck, legs, and wings? Perhaps it is, perhaps not. I’m personally trying to work harder on using more of my birds – largely because of the positive guidance provided on this blog.

As stewards of a wild food resource, I’m just suggesting that we have much further to go than to get 70% of hunters to start using duck tongue, and then everything will be hunky dory. We need to get a very real percentage of hunters to not waste entire animals because they couldn’t bear to not shoot them. Let’s not forget that it still happens to often, and that it is actual wanton waste.