As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Lye. Isn’t that the stuff the Mafia uses to dissolve the bodies of those who’d made an unfortunate choice to use another waste disposal or vending machine company? Isn’t it drain cleaner, a deadly poison? So how on God’s Green Acre can lye be useful in the kitchen?

Relax. I am here to tell you that lye can be your friend, especially when it comes to curing green olives. Good lye cured olives, I have discovered, are uniquely smooth and luscious in a way that brine or water-cured olives can never be. Done right, they can be <gasp!> even better than a brine-cured olive or an oil-cured olive. Seriously.

Let me start by admitting that I was as terrified about using drain cleaner to cure olives as you are. Intellectually I knew it would work, and knew I’d eaten lye cured olives before, as have most of us: They are those nasty black canned things also known as Lindsay olives. That knowledge, however, did not bolster my desire to do any lye curing anytime soon.

Then I did some research. I’d seen all sorts of references to how the lye cure — actually a cure in water that had percolated through wood ashes, which are a source of lye — being used “since Roman times.”

Many hours of searching later, I found that the Roman agricultural writer Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus Palladius is the source of this, in his De Re Rustica, written in the 300s.

“Mix together a setier of passum, two handfuls of well-sifted cinders, a trickle of old wine and some cypress leaves. Pile all the olives in this mixture, saturate them with this paste in garnishing them with several layers, until you see it reach the edges of the containers.”

Passum is freshly extracted grape juice, so the lye in the ash-water interacting with this would make an interesting brew. There would be so much sugar going on in there that you could get both a lye cure and fermentation going at the same time. Freaky.

Since then the Spanish have been masters of lye cured olives. Most Spanish table olives are cured at least in part with lye, but their process is far different than that used in to make the hideous Lindsay olive. I am modifying a method I found in an agricultural book written in 1817.

Incidentally, other popular modern olives that use a lye cure include the French lucques, Italian cerignola and Spanish manzanilla.

First thing you need to know about lye cured olives is that you must use fresh green olives. Not black ones, not half-ripe ones. The lye process softens the meat of the olive, so you want it as firm as possible.

When you are picking your olives, watch out for olive fly. The larva of this nasty little bug burrows into an olive and eats it from within. Thankfully infested olives are easy to spot: They will ripen faster than healthy olives, and there is a tell-tale scar on the olive that looks like this:

Toss that olive. While the worm is not poisonous, I prefer my olives sans extra protein, thank you.

What sort of lye do you use? The traditional brand to use is the classic Red Devil Lye, which is an old brand of drain cleaner. Drano used to be this way, but apparently has additives now. Don’t use it.

I now buy food grade lye because, well, it’s easy to get on Amazon, and I also like making pretzels at home, too, and they use lye to get that signature crust.

Isn’t lye a deadly poison? Sorta. Sodium hydroxide is one of the nastiest bases we know of; a base is the opposite of an acid. On the PH scale, distilled water is the median, at 7. Your stomach acid’s PH is about 1 1/2 — enough to burn a hole through a rug. Lye’s PH is 13.

Bottom line: Raw, pure lye will burn the hell out of you, but it is not a systemic poison. That means that even if you eat an olive that still has a lot of lye in it — as I did — all you will taste is a nasty soapy flavor. If you eat a bunch of them, the alkaline PH in the olives will counteract your stomach acid and it might give you indigestion. That’s all, and that’s a worst-case scenario.

That said, you need to be careful at that one moment you are moving raw, pure lye from the container to the crock you are curing into.

LYE CURED OLIVES STEP BY STEP

Follow these instructions and you will be fine:

- Wear glasses if you have them. Wear long sleeves and pants and closed shoes. You will probably not get lye on you, but better to be safe.

- Pour 1 gallon of cold — not tepid, not hot, but cold — water into a stoneware crock, a glass container, a stainless steel pot, or a food-grade plastic pail. Under no circumstances should you use aluminum, which will react with the lye and make your olives poisonous.

- Using a measuring device that is not aluminum, add 3 tablespoons of lye to the water. Always add lye to water, not water to lye. A splash of unmixed lye can burn you. Stir well with a wooden spoon.

You’re done. You use cold water because the reaction between lye and water generates heat, and the hotter the lye-water solution, the softer the olives will become. Now that it is mixed, the lye solution can’t hurt you, so go ahead and add your olives.

Stir them in with that wooden spoon and put something over all the olives so they do not float. This is vital. Olives exposed to air while curing turn black. Don’t worry, they will absorb the water and sink in a few hours, but to start you need to submerge them.

Let this sit at room temperature for 12 hours. The alkaline solution will be seeping into the olives, breaking the bonds of the bitter oleuropein molecules, which then exit the olive and go into the water. After 12 hours, pour off the solution into the sink. It should be pretty dark in color.

Quickly resubmerge your olives in cold water. You want to minimize the exposure to air. You now have cured olives.

I know, I know, a lot of recipes say to repeat the lye process another time — sometimes three more times — but that will destroy a lot of flavor; there are a ton of water-soluble flavor compounds in an olive that the lye solution washes away. Trust me. Your olives, unless they are gigantic, will not be overly bitter even after just a light, 12-hour lye soak.

Now you need to cleanse your lye cured olives. They will have a fair bit of lye solution within them now. Keep changing the water 2 to 4 times a day for 3 to 6 days, depending on the size of the olives. After 2 days, taste one: It should be a little soapy, but not too bitter. It’ll be bland, and a little soft. Once the water runs clear you should lose that soapy taste.

Time to brine. If you have large olives, make a brine of 3/4 cup salt to 1 gallon of water. And use good salt if you can. You will taste the difference. Kosher salt is OK, but ideally use a quality salt like Trapani, which is from Sicily. It’s not that expensive, but it is worlds better than regular salt.

Let the olives brine in this for 1 week. Keep them submerged, or you will get darkening. After a while they will sink. After 1 week, pour off the brine and make a new one, only this time, use 1 cup of salt per gallon.

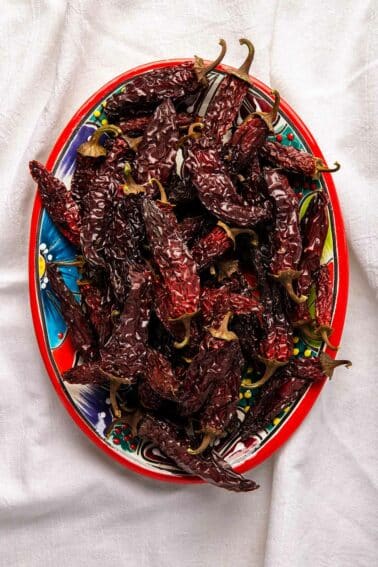

Now you can play. The traditional Spanish cure would add some vinegar to the mix, as well as bay leaf and other spices. I’ve played with adding a touch of smoked salt, chiles, black pepper, coriander, mustard seed, garlic — think Mediterranean flavors.

But before you do this, taste your freshly brined olives. It will be a revelation. They will remain beautifully green, unlike brined olives. Salty, olive-y and very, very buttery. This is the Lay’s Potato Chips of olives. I dare you to eat just one.

First time with the olives, how fun! I’m assuming that with Brine #2, you put them in the jars, or “can them,” as it were. Question: I don’t see where anyone sterilizes the jars. I’ve canned and preserved stuff for years and always sterilize the jars by boiling them before filling them. Is this step necessary with olives? Thank ewe!

Elizabeth: Yes, you can sterilize the jars. I rarely do, and have never had an issue. Clean, yes. Sterile, I haven’t bothered.

Hi, Hank, I’m on day 7 of changing my water 3 times per day. Still lots of color in the water. Should I just move on the salt brine? It’s a very small batch — like 2 pounds.

Thanks,

Tiffany

Tiffany: I’d try an olive to see. If it’s not soapy, move to the brine.

Hello Hank, I drained the lye off of my olives when it had penetrated approximately 3/4 the way to the pit, which I now believe was too soon. I have since washed them just put them in the brine. Unfortunately, I think I didn’t cure them in the lye long enough because they’re still a little too bitter. Can I re-wash the brine out and place them in the lye again? Thanks, Mark

Mark: I have never tried that. If it were me, I would toss them and start again.

I have sorted my olives by color. Could I use less lye in the solution for the olives that have some color on them so they don’t get soft?

I went ahead and just mixed them all together and they are fine. Can you tell me how you store your olives? Do you can them or put them in the refrigerator?

I brine them and keep them in a cool place, like a basement or fridge. They keep indefinitely that way.

Hi Hank. Trying your method of brining for the first time. Can you give measurements for your added spices

Thank you

Peggy: No. Sorry, I never measure, and every batch is different.

Hey Hank, I cured 3 five gal plastic buckets, not completely full. Two of them taste great, the third is a little bitter. Maybe I didn’t use enough lye. Should I just brine it longer? Please advise.

I have made olives for 4 years using your recipe, always great.

Bob: Yes, I’d brine it a little longer.

Hi, when pouring off the lye water, do I rinse them till the water is pretty clear? Or, just pour off the lye water and refill the container with fresh cold water? This question is fo the first part of the recipe, before salt is added.

Thanks

Helen: Just pour off the lye water at first, then, towards the end of the process, you can rinse the olives themselves.

Hank –

I cured my olives for 16 hours in a 2 ounce per gallon lye solution and rinsed them for two days. I still have some bitter taste. The olives are yellow to the pit so it looks like the cure made it to the pit but I still taste some bitterness. Should I do another light lye solution or just continue with rinsing and brining?

John: Is the bitterness too much for you? If so, do a 1/2 strength lye soak one more time. I like a touch of bitter in the olives, but not so much it is off putting.

Thank you. The bitterness was a little strong so I did a 10 hour cure at half the original strength. I need to work out my method and write it down so I remember it.

Hi Hank,

I’m trying this for the first time. After starting the 2nd brining with aromatics, how long until they are ready to eat? Also, how to can them for long term storage, can they be sealed in Kerr jars in a hot water bath, or will the heat be bad for the olives? Thanks so much!!

David: I usually wait at least a week, sometimes two, before I start eating them. Heat is bad for olives, and they will keep in the fridge for many months.

I think we left the olives in the lye too long and they’re peeling. Is it ok to continue with the brine process?

C Johnson: Peeling? That’s a new one. I have no idea what happened there. Sorry.

I had the same happen to

Me. They were a different variety olive , I don’t which but we’re very large and ripened about a

Month before my regular ones I do. I rinsed them the best I could

It Made no difference to the taste they were still very good.

I didn’t wash before the lye solution some say that will

Cause the peeling

Hey hank , followed your directions which was a lot easier than my previous try and during the rinsing phase a lot of my olives were soft. Any ideas on why this happened?

Cal: They’re supposed to be softer, but if they are mushy, that means the olives were riper. I only like the lye cure with unripe green olives.

Just want to say how much I appreciate this recipe. I’ve been making it for three years, blogged it with links and attribution over at Foodaism, and brought many others into the lye-cure club. For Angelenos, best source is Sunland Produce, where fresh green olives are 1.25/lb during the short season.

Hey Hank

Without really thinking about the difference I’ve cured my olives in lime (calcium hydroxide) instead of lye (sodium hydroxide) as I have it on hand for nixtamal any idea if this will still work?

Nigel: Never tried it!

Well. Turns out it doesn’t really work. Did some research on the difference between the two chemicals (prob should have done first) and long story short calcium hydroxide is not as caustic and not as water soluble as sodium hydroxide so maybe that’s why my olive are still bitter and turned brown. Oh well, live and learn.

Hi Hank. I’ve been following your recipe for year with great results. This year however, my green olives shriveled during the brining process. They still taste fine but look a little anemic. Any idea?

Peter: Huh. No idea why this year would be different if you’ve had good results in the past.

Hey hank! This happened to me in 2020 as well. What i did was rinsed them off the brine and soaked them in plain water for 24 hours. They plumped back up and then i reduced the amount of salt in the brine by 1/4 and then they were good to go into the finishing brine.

Hey Hank,

Thanks for posting this recipe. My grandpa used to cure olives like this too. I have a question. I am in the rinsing phase and I’m now on day 6, with 3 water changes per day and I am still no getting clear water. Should I continue to as-is or should I move onto the brining phase?

Thanks!

Hi Hank:

I have some beautiful green olives I preserved years ago with the lye solution and then the brine but they have an astringent after taste, is it possible to make them more palatable or should I discard them altogether?

Naomi.

Naomi: I’d toss them.

Your research into the difference between food-grade and technical grade sodium hydroxide (lye) was not thorough enough. The difference is in the allowable amount of impurities, including toxic heavy metals, and the extra Quality Assurance and Quality Control that go into ensuring the higher level of purity. Food grade costs more because of the extra steps needed to produce it, but it’s still very affordable stuff. There is no reason to risk health by using technical grade NaOH.

Hi Hank! I have followed your lye-cured olive instructions to the letter (thanks you for all that great info) and I am one water change away from the brining process. My olives are medium size so do I still use 3/4 C salt/one gallon water for the first brine? For the second brine, with added aromatics etc., do I leave the olives in that salt+aromatics solution in my fridge or…? First time I have done this so I apologise if my questions have obvious answers. Thanks, Howard

Howard: Yep you still follow the instructions for that first brine. When you switch to aromatics, I generally make sure the olives are in a cool place. Basement, cool closet, fridge. Shouldn’t be too hard right now, but once the weather warms, you will want to move them to the fridge.

Hank – you didn’t crack your olives. Is that not necessary?

Frank: Not at all for lye cured olives.

Hi Hank, thanks for posting this recipe. I am on the one week brine stage. I’m unclear on the second brine. I am using 5 gallon buckets. Can I make the second brine in the buckets then transfer them into jars immediately?

Also do you think a couple of garlic cloves per pint is okay for flavor?

Shawn: Yes, you can do both of those things.

Hi Hank:

Have done olives with lye a few times and again, successfully, this year. Also, however, am trying some “cracked” olives in a salt brine. About 20 pounds in 2.5 gallons of water. Began with a 6% salt solution. Increased that to 8%. Still bitter after about 10 days so I changed the water and went to 10% (10-1) salt ratio. They’re still a little bitter and don’t seem to be improving. The water was pretty dark so I just changed the salt/water with another 10% solution.

These are Napa Valley (Mission, likely) olives and were broken in a heavy bottom pot using a one foot cut of a clothes pole and a hammer. Breaking them in the pot avoids most of the splatter and goes pretty quick as you can put 10-12 in the pot at a time.

Thanks in advance for the input.

Ron: I don’t use that method anymore, as I don’t like the end product. But I can tell you that straight brine cured olives can take months to de-bitter.

Hi

I also have some olives that are partially black and having a hard time getting the lye taste out after many rinses. What am I doing wrong

Linda: Not sure. I’d toss them.